The year 2017 gave us some remarkable reads. From thriller to young adult, self-help to professional, we got ‘em all! So, if you are looking to round-up the year, here are 7 books out of those magnificent reads.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

The year 2017 saw the return of the Man Booker Prize Winner Arundhati Roy into the fiction genre with The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. This ravishing, magnificent book reinvents what a novel can do and can be. And it demonstrates on every page the miracle of Arundhati Roy’s storytelling gifts.

The House That Spoke

The House that Spoke marks the debut of fifteen-year-old author Zuni Chopra. It tells the story of Zoon Razdan and the fantastical house she lives in. She can talk to everything in it, but Zoon doesn’t know that her beloved house once contained a terrible force of darkness. When the dark force returns, more powerful than ever, it is up to her to take her rightful place as the Guardian of the house and subsequently, Kashmir.

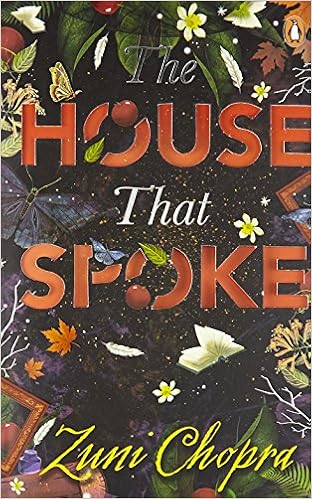

Vyasa

With 1600 electrifying visuals for hot-hearted adults- Vyasa sets in motion the battlefield of Kurukshetra. From the birth of the Pandavas and Kauravas to the interpenetration of life instincts and death instincts, this first book in this graphic book series rolls out the beginning of interplay of lust and violence which gives to the tale of war, revenge and peace the unmatched regal look.

The Case That Shook India

On 12 June 1975, for the first time in independent India’s history, the election of a prime minister was set aside by a High Court judgment. The watershed case, Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain, acted as the catalyst for the imposition of the Emergency. Prashant Bhushan in The Case That Shook India provides a blow-by-blow account and offers the reader a front-row seat to watch one of India’s most important legal dramas unfold.

Friend of my Youth

Amit Chaudhuri in Friend of My Youth tells the story of a writer in Bombay for a book-related visit and finds himself in search of the city he grew up in and barely knows. Friend of My Youth is at once an unexpected exploration and a concentrated reminiscence woven around a series of visits to a city that was never really home.

Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth

Aurangzeb reveals the untold side of a ruler who has been peddled as a Hindu-loathing bigot, murderer, and religious zealot. In this bold and captivating biography, Audrey Truschke enters the public debate with a fresh look at the controversial Mughal emperor.

Padmini: The Spirited Queen of Chittor

Mridula Behari’s Padmini is narrated from Padmini’s perspective and is a moving retelling of the famed legend that brings to life the atmosphere and intrigue of medieval Rajput courts. You cannot help but be engrossed as Padmini grapples with the matter of her own life and death, even as she attempts to figure out what it means to be a woman in a man’s world.

So, which was your favourite read of 2017?