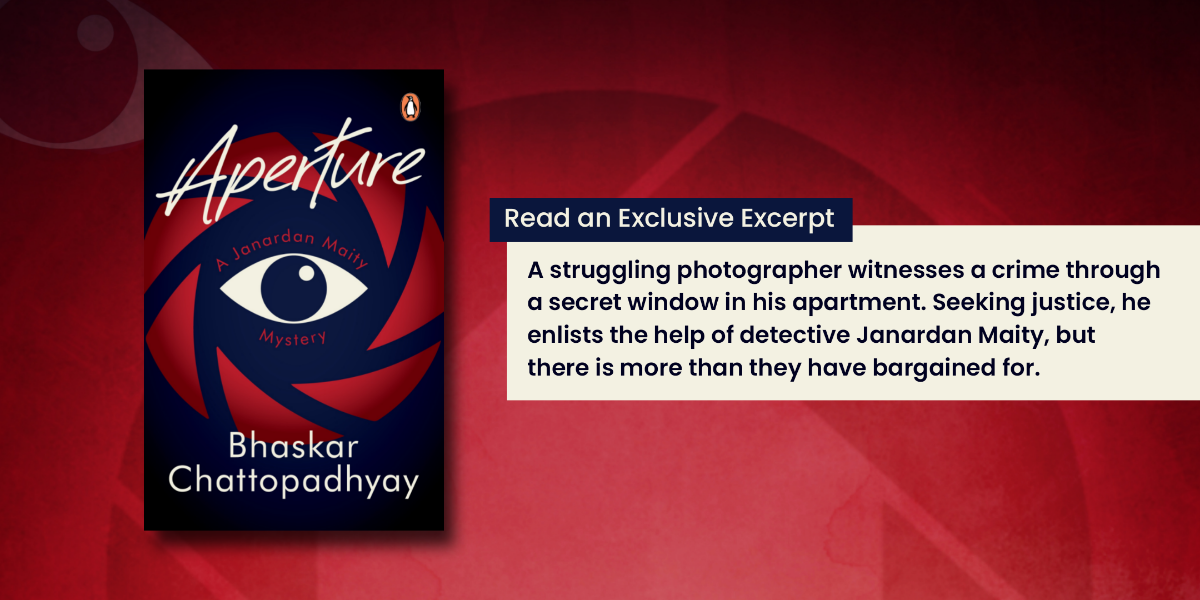

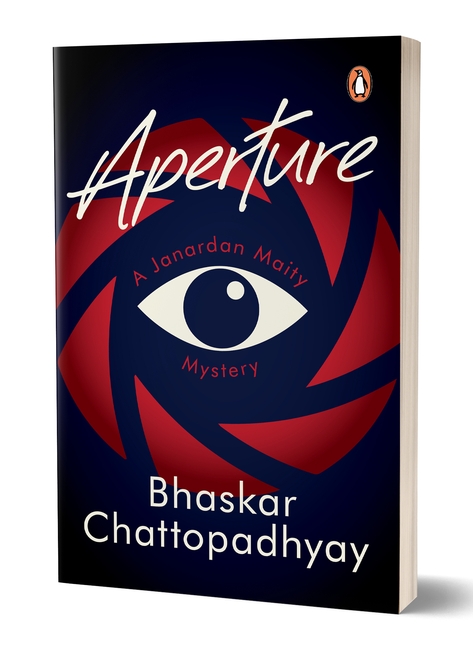

What happens when a struggling photographer’s secret hobby turns into a dangerous game? In Bhaskar Chattopadhyay‘s latest book, Aperture a photographer becomes obsessed with spying on people in a shady hotel through a hidden window in his apartment. When he witnesses a murder, he turns to detective Janardan Maity for help, but there is more than they have bargained for!

Read this exclusive excerpt and join them on a thrilling investigation.

For several seconds, there was a heavy and distinctly uncomfortable silence in Maity’s sprawling drawing room. Maity’s expression was calm but serious. Sayantan Kundu had sunk back in his chair, clearly exhausted after letting the burden of his truth out. I, on the other hand, was wondering what was going on in Maity’s head presently. Was he excited at the prospect of having to deal with such a bizarre set of events? Or was he disgusted by the young photographer’s heinous acts? I figured it was a bit of both.

‘I suppose,’ Sayantan finally said, ‘you would want the specifics.’

‘You suppose correctly,’ came Maity’s response. Sayantan took a few seconds to find the words. Then he said: ‘It happened exactly a week ago. On Tuesday, the nineteenth of June. It was a hot day, but a brief spell of rain in the afternoon had cooled things down a little. A young couple had checked into one of the rooms on the third floor—the same level as I live in my own building. Seemed like a honeymoon couple. The woman was pretty, but a— how shall I say—coarse sort of pretty. Long straight hair. Poorly-done henna on her palm. Glass bangles. Overdone makeup. The young chap was rugged and good-looking.

It seemed to me that they . . . they weren’t very well off. I mean why would they be in that hotel otherwise? But . . . they did seem to be in love. Deeply. They were having a good time and not just in a sexual way. They would talk for hours on end. Sometimes, I would get bored. But as you can imagine, Mr Maity, in this profession, we are not allowed to get bored. I waited for my chance. Sometimes, it seemed it would come. They would cuddle, kiss, get cosy. I’d get some good shots. But then they would break off. As if . . .as if something was stopping them, as if there was a barrier between them.’

Maity and I were listening with such rapt attention that I had not even noticed when Mahadev had come and taken the empty cups away.

‘They would seem . . . sad. But then it was the woman mostly who would cheer up, throw her arms around her husband and embrace him. They would go to bed. That was when I would get the . . . the real shots.’

‘From your room,’ Maity said. ‘Are you ever able to hear anything that happened in the rooms of that hotel? Any sound of any kind?’

‘No. After I got into this . . . business, I invested in a tinted glass, had it installed on the ventilator opening. I can see everything clearly from my side of the window. But no one would be able to see me from the other side. Plus, I chose the colour of the glass in such a way that it would camouflage my window. One disadvantage of doing all this, though, was that I would hear absolutely nothing, no sound from the other side.’

‘I see,’ nodded Maity. ‘Interesting, very interesting!’

‘Anyway, I got some really good shots of the couple. In . . . in the act, you know? Shots that would suffice for my purpose. The best shots are the ones that show the faces clearly. I’m sorry you are having to hear all these details, but . . .’

‘As despicable as your crimes are, Mr Kundu,’ Maity interrupted, ‘I’m afraid the details are important. That’s usually where the devil resides.’

‘I understand,’ Sayantan nodded. ‘Like I said, I got some good shots. But that night, while they were in the . . . you know . . . the height of their act, something else caught my attention through the lens. At first, it seemed quite funny to me. In fact, I remember having chuckled behind my camera. The room exactly below them was occupied by a middle-aged couple. Perhaps in their late forties or early fifties. They had checked in a day before, on the eighteenth. When the younger couple were having sex, I could see the middle-aged couple look up at the ceiling of their room. They could obviously hear the noises coming from the room above. And they were clearly not amused. The wife said something to the husband, the husband replied angrily. There was a brief quarrel between the two. It was amusing, to be honest . . . this . . . this contrast between what was going on in those two rooms. One on top of the other.’

‘What happened then?’

‘The quarrel stopped after some time. The woman went to bed, held a pillow over her ear. That didn’t seem to work, because she flung the pillow across the room, and it almost hit her husband. The husband yelled at her—she yelled back. That’s when the real quarrel started. It all came to blows. The wife seemed furious.’

‘And this young couple in the room above . . .’ Maity interjected with a suggestion of a question.

‘Yes,’ nodded Sayantan, ‘they had . . . finished by then. They were exhausted. The couple below were now in a bitter fight. The woman had started slapping her husband left, right and centre. She was screaming and sobbing. The husband was taking all the hits. But after a while, he punched his wife right across the face. Sent her flying across the room and on to the bed.’

‘He . . . he killed her?’ I asked, apprehensively.

***

Get your copy of Aperture by Bhaskar Chattopadhyay on Amazon or wherever books are sold.