Loya is twenty-five: solitary, sincere, with restless stirrings in her heart. In an uncharacteristic move, she sets off on an unexpected journey, away from her mother, Rukmini, and her home in Bengaluru, to distant, misty Assam. She seeks her grandfather, Torun Ram Goswami, someone she has never met before.

Twenty-five years ago, Rukmini – Loya’s mother – had been cast out of the family home by her mother, the formidable and charismatic Usha, while Torun watched silently. Loya now seeks answers, both from him and from the place that her mother once called home.

The story of Torun and Loya is filled with heavier, unspoken moments of regret, longing, , love and connection – punctuated with some mundane banter that bring them both closer. We take a look at some of these that made their relationship all the more poignant for us.

Little Moments

Every relationship has its own quirks and mundanities. Loya and Torun are no different; and their periodic games of scrabble are quite heartwarming.

Despite his old age and slipping memory, Torun proceeded to trounce Loya at every game. So much for youth.

‘It is that electronic junk that is turning your brain to mush!’

Torun waved at her phone and laptop.

As Torun deliberated over his move, Loya thought of how Roy had laughed when he heard of the scrabble games with her grandfather. She had been angry, but held back from a response. These days she was holding back on all emotions with Roy.

AFFORESTATION. Torun made a long word.

Loya laughed. ‘Good word!’

*

Holding Back

With the history between them, there is a certain precariousness to their relationship in the beginning. We were touched by Torun’s apprehension in the beginning, where he longed to be called koka – Assamese for ‘grandfather’ – by Loya.

Torun scowled. The girl still refused to call him koka, although she had no trouble addressing Robin as one.

He took a deep breath. He saw Rukmini’s beloved face in front of him; it was cocked like hers, as if the heavy braid was too much for her small head. She smiled at him. Torun’s eyes filled unexpectedly.

‘Majoni,’ he said to Loya, ‘My dear girl. I am so sorry for all that has happened. Let me do what I can now.’

*

Koka

When Loya finally gets around to addressing Torun as her grandfather, our hearts swelled right with Torun.

For three full days Torun hugged the word to himself.

Koka. Grandfather.

‘What’s going on, Deuta?’ Romen teased. ‘You look pleased.’

‘You won’t understand.’

‘Try me!’

‘It’s a secret.’

‘As long as you are happy.’

The girl was stretched out on a sofa, reading. Torun looked at her for a moment.

He was happy.

*

Unspoken Love

This particular moment between the two of them carried exceptional emotional weight for us.

The girl then rose from her seat and came across to him.

She squatted and put her long arms across his shoulders. ‘I love

you, I think, Koka.’

He watched her make her way back to her bedroom and drained the last of the amber liquid into his glass. He swallowed the last words, lest they escaped him.

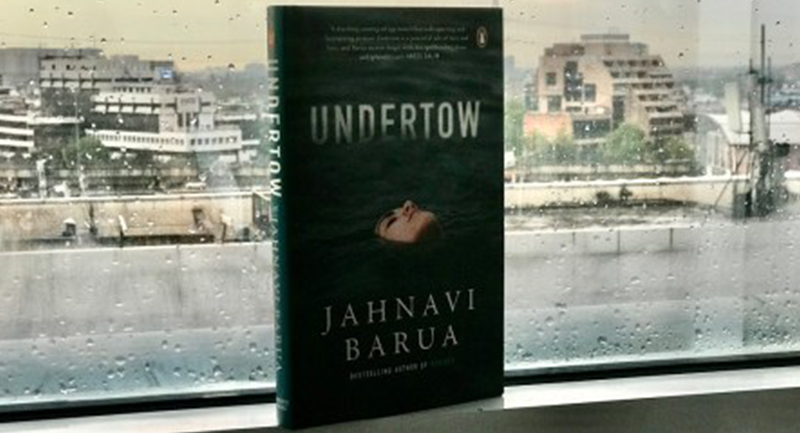

A delicate, poignant portrait of family and all that it contains, Undertow is an exploration of much more: home and the outside world, the insider and the outsider, and the ever-evolving nature of love itself.