The decade spanning 1978 to 1988 saw the terrifying rule of Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan. In a Lahor under Martial Law, we meet Ikhlaq and his family, who are struggling to build a home in the city.

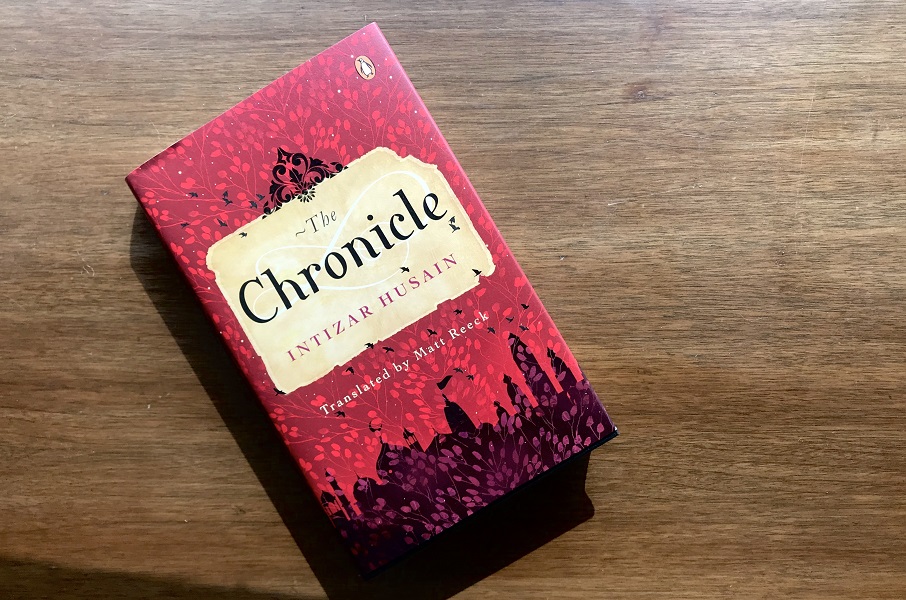

Set in a troubled time and leadership, The Chronicle by the celebrated Pakistani author Intizar Husain – translated by Matt Reeck – tells the epic story of a family and its illustrious homes. The reader is introduced to a dramatic and darkly comedic chain of events through Ikhlaq’s voice.

We are here to introduce you to our main character! Read on to meet Ikhlaq:

A Storyteller

When he finds the manuscript of the tazkirah, his family chronicle, he decides to continue writing the story as the last chapter has become illegible. Ikhlaq is both a reader and storyteller, and we are introduced to his world entirely through his voice.

‘I thought that, in the end, I was of the same blood as my ancestors, so why wouldn’t I want to continue writing the chronicle? Why hadn’t I seen any such desire in my father? All he had done was to make sure that the chronicle had not been destroyed.’

*

A Family Man

His desire to continue the chronicle in an effort to safeguard and maintain his family’s history also presents Ikhlaq as a family man. His excitement and engagement with the family chronicle also reaffirms this point.

‘…I began to find some pleasure in deciphering [the chronicle]. I began to feel that I should see what the pages contained so as to figure out what it was about my family that in every generation someone took it upon himself to sit down with an inkpot and start writing. With such concentration they had written down the histories of the family—as though they were leaving for their children a valuable piece of property.’

*

Nostalgic for What his City Used to be

With Haq’s rule, Ikhlaq’s life and environment have become very dynamic, and we often find him reminiscing about his home and how much the world around him has changed.

‘I got the feeling that the world had really changed, and the city was something altogether new. I thought about how the city used to be. I remembered a fall afternoon. There was a carpet of yellow leaves on the street […]How many city streets from the Red House to Mall Road did I imagine in this way, each one covered with fall leaves?’

*

Restless for Home

His search for a house, struggles with the rising rent, and eventual attempts to build a house for him and his family tell us of his inherent desire to find a home, stability and peace in his ever-changing life.

‘Maybe I felt restless because I didn’t have a house.

Maybe if I had a place to lay my head and rest my feet, I would find some peace of mind. So building a house, which would soon drive me crazy, became something to think about. I started to share the worries of my co-workers. These men had been going back and forth to their housing development’s offices.’

*

Desire for Freedom

Ikhlaq’s life and feelings act as microcosms for the larger desire of freedom in Haq’s Pakistan. His act of building a new house and neighbourhood give Ikhlaq a powerful insight into both the desire and the fear of freedom.

‘Finally I understood why people were fleeing the alleys for the new neighbourhoods. I had thought they were doing so just to show off their new wealth. But I realized that they were tired of alleys. after hiding from the land and the sky, they grew weary of the tight alleyways and the tall houses. It’s so difficult. The one doesn’t let you breathe, but neither does the other. People are scared of the open land and the endless sky. But they also grow tired of the claustrophobia of alley after alley and house after house. So after having left behind the fear of the open land, we grew of tight quarters.’

Step into the lanes of Lahore and Ikhlaq’s ever-changing life in The Chronicle!