India’s freedom from the British rule was stained by the horrors of its partition. The reverberations of the event over the last seventy years have been encapsulated in several books, plays, and other forms of media.

Here is a list of 25 books that capture one of the most defining moment of our history.

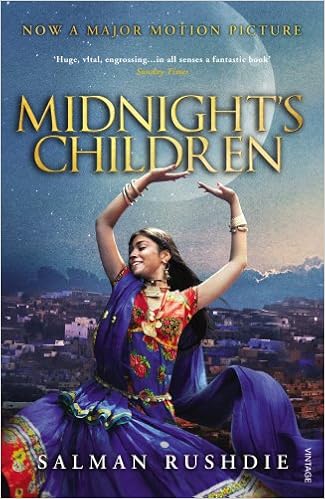

Midnight’s Children

Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie is an epic novel that opens up with a child being born at midnight on 15th August 1947, just at a time when India is achieving Independence from centuries of foreign British colonial rule. Highlighting the relation between father and son and a nation yet in its nascent stage, it is an enchanting family adventure with lots of human drama and shocking summoning.

Lifting The Veil

Ismat Chughtai in Lifting the Veil explored female sexuality with unparalleled frankness and examined the political and social mores of her time.

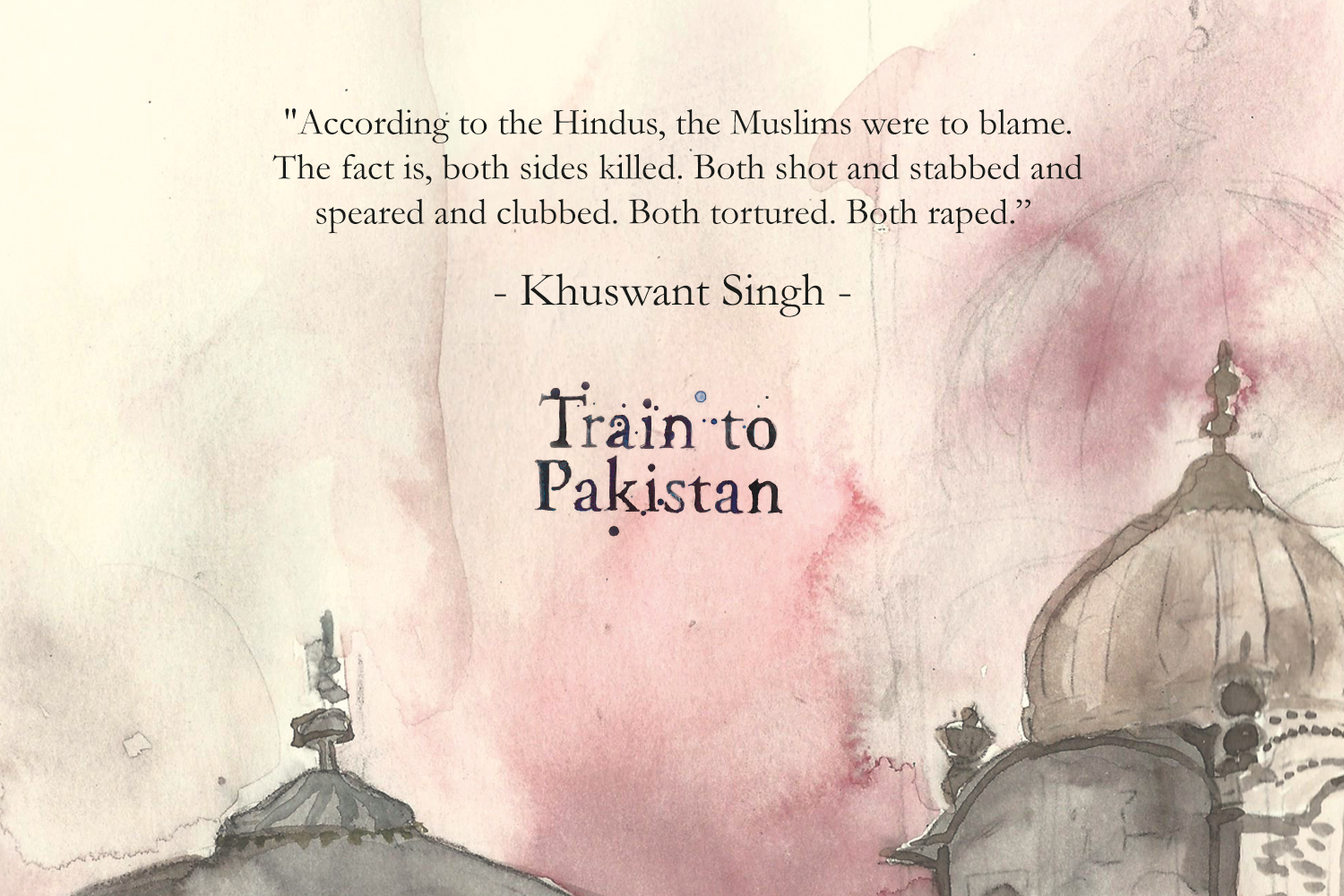

Train to India: Memories of Another Bengal

As a young boy, Maloy Krishna Dhar, made the perilous journey to India from the East Pakistan. The partion in Bengal had its share of tragedy, of lives unmade and lost, but it is relatively less chronicled than events in Punjab. Maloy Krishna Dhar’s Train to India is a graphic and moving account of that turbulent and unforgotten era of Bengal History.

The Shadow Lines

As a young boy, Amitav Ghosh’s narrator in The Shadow Lines travels across time through the tales of those around him, traversing the unreliable planes of memory, unmindful of physical, political and chronological borders. Bits and pieces of stories, both half-remembered and imagined, come together in his mind until he arrives at an intricate, interconnected picture of the world where borders and boundaries mean nothing, mere shadow lines that we draw dividing people and nations.

Midnight’s Furies

Nisid Hajari’s Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition shows how Partition, which has created such a wide gulf between two countries whose people have so much in common, has given birth to global terrorism and dangerous proliferation.

Sunlight On A Broken Column

On a backdrop India’s struggle for independence, Laila, an orphaned daughter of a distinguished Muslim family, fights for her own independence from the claustrophobia of a traditional life. With its beautiful evocation of India, its political insight and unsentimental understanding of the human heart, Sunlight on a Broken Column, first published in 1961, is a classic of Muslim life.

Partitions

With India’s partition in 1947 as its reference point, the novel presents a limitless canvas against which the most extraordinary trial in the history of mankind runs its course. Kamleshwar’s Kitne Pakistan dared to ask crucial questions about the making and writing of history.

Amritsar to Lahore by Stephen Alter

A sensitive and thoughtful look at the lasting effects of Partition on everyday people, Amritsar to Lahore describes a journey across the contested border between India and Pakistan in 1997, the fiftieth anniversary of Partition. Offering both the perspective of hindsight and a troubling vision of the future, Amritsar to Lahore presents a compelling argument against the impenetrability of boundaries and the tragic legacy of lands divided.

The Broken Mirror

The Broken Mirror by Krishna Baldev Vaid tells the story of Beero and his group of friends against a backdrop of partition of India. Beero’s passage through adolescence is told through a series of eccentric characters. When partition becomes a reality, in a time of terror and carnage, the insane turn out be the only ones sane.

Unbordered Memories

If Partition affected the lives of Sindhi Hindus, it also changed things for the Sindhi Muslims. In Unbordered Memories, Sindhis from India and Pakistan make imaginative entries into each other’s worlds. Many stories in this volume testify to the Sindhi Muslims’ empathy for the world inhabited by the Hindus, and the Indian Sindhis’ solidarity with the turbulence experienced by Pakistani Sindhis.

Making Peace With Partition

The Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 left a legacy of hostility and bitterness that has bedevilled relations between India and Pakistan. Reviewing the turbulent history of their past relationship, Radha Kumar analyses the chief obstacles the two countries face in the light of the new opportunities and challenges that the twenty-first century presents.

Bitter Fruit: The Very Best of Saadat Hasan Manto

Manto’s stories were mostly written against the backdrop of the Partition. Bitter Fruit presents the best collection of Manto’s writings, from his short stories, plays and sketches, to portraits of cinema artists, a few pieces on himself. Bitter Fruit includes stories like A Wet Afternoon, The Return, A Believer s Version, Toba Tek Singh, Colder than Ice and many others.

Kingdom’s End: Selected Stories

This collection brings together some of Manto’s finest stories, ranging from his chilling recounting of the horrors of Partition to his portrayal of the underworld. Powerful and deeply moving, these stories remain as relevant today as they were first published.

Mottled Dawn

Mottled Dawn by Saadat Hasan Manto is a collection of stories based on the India-Pakistan partition. The stories written around 1947 put forward the most tragic events in the history of the subcontinent.

Manto: Selected Stories

Saadat Hasan Manto’s stories are vivid, dangerous and troubling and they slice into the everyday world to reveal its sombre, dark heart. These stories were written from the mid-1930s on, many under the shadow of Partition. No Indian writer since has quite managed to capture the underbelly of Indian life with as much sympathy and colour.

India Divided

Written by the first President of India, India Divided traces the origins and growth of the Hindu–Muslim conflict, gives the summary of the several schemes for the partition of India which were put forth, and points out the essential ambiguity of the Lahore Resolution. Finally, it concludes that the solution for the Hindu–Muslim issue should be sought in the formation of a secular state, with cultural autonomy for the different groups that make up the nation.

Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage That Shook India Sheela Reddy in Mr and Mrs Jinnah brings forth the marriage that convulsed the Indian society with a sympathetic, discerning eye. A product of intensive and meticulous research in Delhi, Bombay and Karachi, and based on first-person accounts and sources, Reddy sheds light on how the politics of the time affected the marital life of misunderstood Jinnah and wistful Ruttie.

Sheela Reddy in Mr and Mrs Jinnah brings forth the marriage that convulsed the Indian society with a sympathetic, discerning eye. A product of intensive and meticulous research in Delhi, Bombay and Karachi, and based on first-person accounts and sources, Reddy sheds light on how the politics of the time affected the marital life of misunderstood Jinnah and wistful Ruttie.

Tamas

A timeless classic about the Partition of India, Tamas is also a chilling reminder of the consequences of religious intolerance and communal prejudice.

Bengal Divided: The Unmaking of a Nation (1905-1971)

In 1905, all of Bengal rose in uproar because the British had partitioned the state. Yet in 1947, the same people insisted on a partition along communal lines. Exploring the roots of alienation of the two communities, Nitish Sengupta peels off the layers of events in this pivotal period in Bengal’s history, casting new light on the roles of figures such as Chittaranjan Das, Subhas Chandra Bose, Nazrul Islam, Fazlul Huq, H.S. Suhrawardy and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee.

Looking Through Glass

In Mukul Kesavan’s Looking Through Glass, a young photographer on a train to Lucknow suddenly finds himself in the deep end of 1942. His hindsight tells him that Partition will destroy this world. And in his desperate struggles to avert the inevitable, we discover, often with an almost unbearable poignancy, how the possibilities in India’s past were squandered, some wantonly, others accidentally.

Regret

A collection of two novellas—Regret and Out of Sight, the stories skilfully evoke the long shadow cast by the violence of Partition. While Regret brilliantly recreates a childhood shattered by the Partition of India in 1947, Out of Sight recounts the story of Ismail, who narrowly escaped the carnage of 1947 in his youth. Now, looking back on his life and despairing of the sudden resurgence of sectarian violence in Pakistan.

Memories Of Madness: Stories Of 1947

The tragic legacy of Partition haunts the subcontinent even today. Memories of Madness brings together works by three leading writers who witnessed the insanity of those months—Khushwant Singh, Saadat Hasan Manto, and Bhisham Sahni. As moving as they are disturbing, the stories in this volume are of immense relevance in these times, for they constitute a chilling reminder of the consequences of communal politics.

The Other Side of Silence

Pieced together from oral narratives and testimonies, in many cases from women, children and dalits— marginal voices never heard before— and supplemented by documents, reports, diaries, memoirs and parliamentary records, this is a moving, personal chronicle of Partition that places people, instead of grand politics, at the centre.

Partition: The Long Shadow

The dark legacies of partition have cast a long shadow on the lives of people of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The borders that were drawn in 1947, and redrawn in 1971, divided not only nations and histories but also families and friends. The essays in this volume explore new ground in Partition research, looking into areas such as art, literature, migration, and notions of ‘foreignness’ and ‘belonging’.

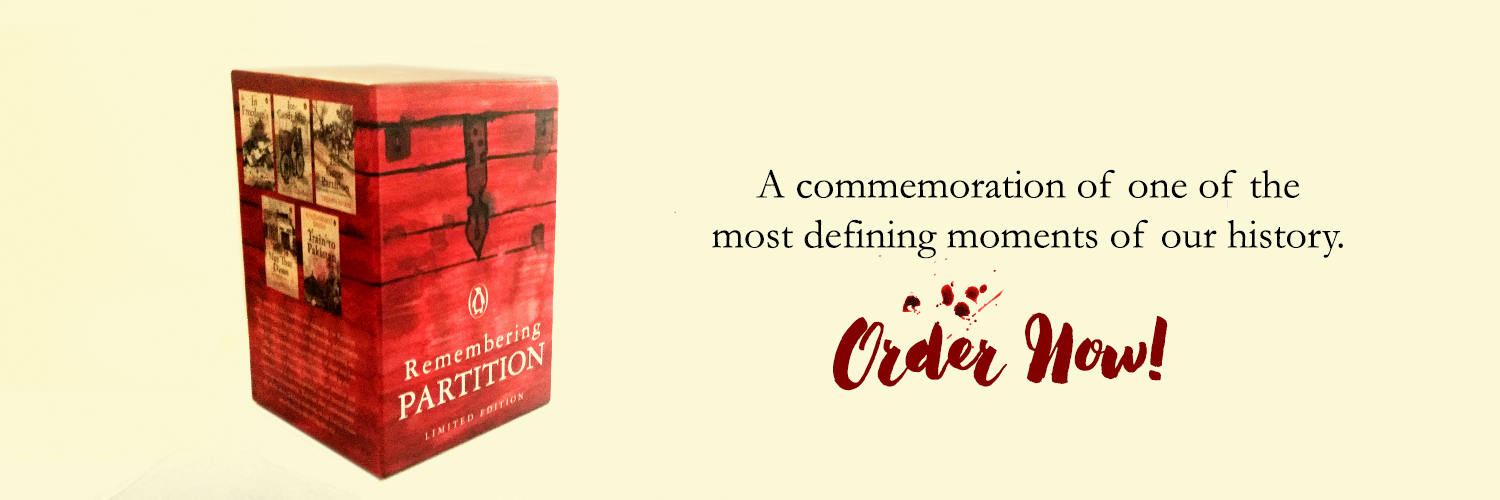

Remembering Partition: Limited Edition

The Remembering Partition Box Set is a collection of five iconic books which look at the different faces of partition, from the larger political and historical view to the very personal tales of hatred, grief, courage and friendship.

On the 70th anniversary of partition, which book are you picking?