When protests erupted at JNU, students found themselves labeled as “anti-nationals,” sparking a nationwide debate on patriotism. Slogans like Bharat Mata Ki Jai and Jai Shri Ram transformed from symbols of pride into charged political expressions. This book explores these events, from JNU to the farmers’ protests, unearthing the deepening divides over what it means to be truly patriotic.

Read the excerpt below for a powerful glimpse into India’s evolving identity.

Time: Sometime in 2019

Place: A WhatsApp group of friends

Adnan: Not sure how all of you will take my comments but the political situation really worries me. Over the last five years the BJP has polarized votes to such an extent that political parties are shying away from giving tickets to Muslim candidates. I mean they feel just by doing it, it will cost them the Hindu vote bank.

Ahmed: You are right, the Congress, in particular, has reduced the number of tickets to Muslims due to fear that it will backfire electorally. No one is really willing to confront the BJP on its practice of exclusion of Muslims. They are afraid of being branded pro-Muslim, and therefore anti-Hindu.

Mohammad Sajjad: Truly. I believe this whole concept of Hindu majoritarianism is aimed at making India’s Muslims electorally irrelevant.

Ahmed: I think the fault also lay in the fact that the Congress looked at Muslims only as a ‘vote bank’ and did little to promote leadership within the community.

Mohammad Ashfaq: I don’t even think it is just a Muslim issue. I think the Congress, for one, needs to rethink its politics not just for the sake of Muslims but to salvage its own image as a party that is committed to the constitutional principles of secularism and pluralism.

Hasan: Whatever it is, I hope good sense prevails sooner rather than later and as a country we do not lose our pluralistic ethos.

* * *

Hobson’s Choice

‘Some sections of society have an impression that the party is inclined to certain communities or organisations. Congress policy is equal justice to everyone. But people have doubts whether that policy is being implemented or not. This doubt is created by the party’s proximity towards minority communities,’ A.K. Antony, veteran Congress leader, said.

After the Congress Party faced a resounding defeat in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, being relegated to as low as forty-four seats, a review committee set up under A.K. Antony’s leadership found minority appeasement to be one of the major causes of its electoral loss. It was found that a significant section of Hindus felt that most non-BJP parties overlooked their interests and focused mainly on minorities. It didn’t help that the BJP seemed to be advancing the notion that the Congress Party and the other so-called secular parties engaged in religious pandering to secure their Muslim vote bank in the garb of secularism.

Post the 2014 elections, it stands to reason then that there was little talk of secularism by parties as there was the potent fear of being labelled ‘minority appeasers’. From the A.K. Antony report to the more recent Raipur Plenary of the Congress Party (the 85th plenary session of the Congress that concluded in Raipur in Chhattisgarh outlined a strategy for the 2024 Lok Sabha election) ‘how to remove the anti-Hindu tag’ has been a key focus area within the Congress. The obvious solution was to pivot to brandish their own Hindu credentials to blunt the BJP’s appeal. In the words of political activist Yogendra Yadav, ‘Secular politics faced a Hobson’s choice: it could take a “hard” line and face electoral marginalization. Or it could go for “soft Hindutva” and betray its cause.’

Whether it meant betraying their cause or not, most opposition parties chose the latter. While it may seem ironic that the cure for the BJP’s marginalization of the Muslims was to make the Congress more Hindu, the Congress Party’s manifesto in Madhya Pradesh in 2018 included setting up gaushalas, or cow shelters, in each of the state’s 23,000 panchayats; it also committed itself to developing the Ram Van Gaman Path, or the route that was taken by Lord Rama on his way to exile that was widely revered by Hindus.

Despite these sporadic efforts, the 2019 Lok Sabha polls turned out to be an encore for the BJP, with it garnering the highest-ever national vote share. According to Lokniti-CSDS’ post-poll survey for the 2019 elections, the BJP and its allies managed to secure close to 52 per cent of the Hindu votes all over India, the highest consolidation of Hindu votes nationally in three decades. Intriguingly, the oath-taking ceremony for members of Parliament to the seventeenth Lok Sabha was drowned in shouts of ‘Jai Shri Ram’; the chant particularly gaining decibels during the oath-taking of specific members of the Opposition.

***

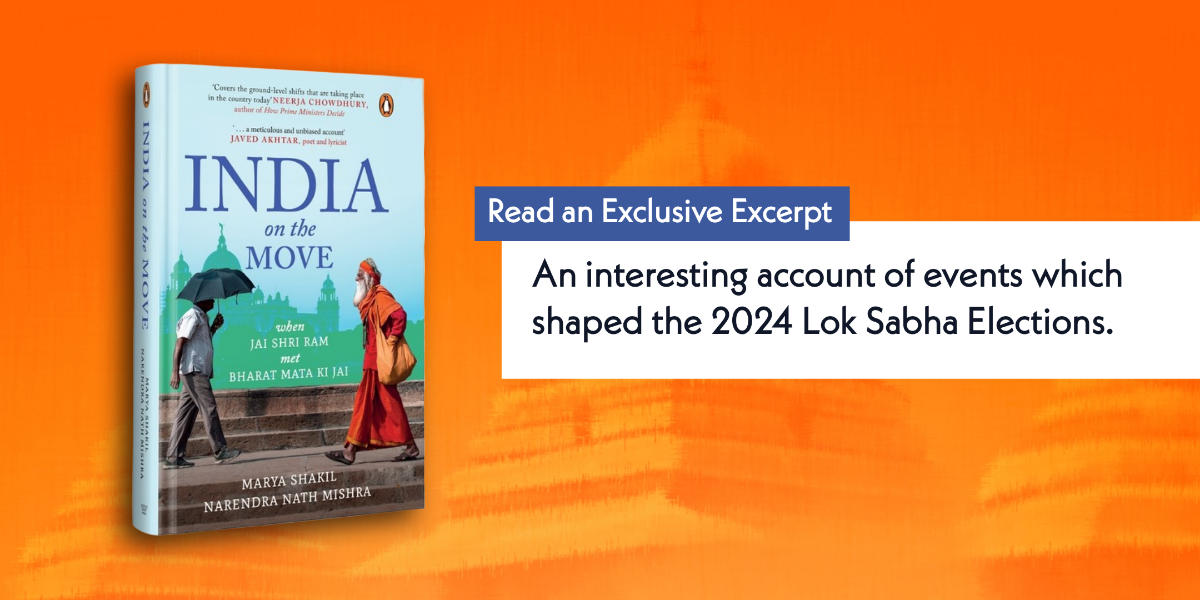

Get your copy of India on the Move by Marya Shakil, Narendra Nath Mishra on Amazon or wherever books are sold.