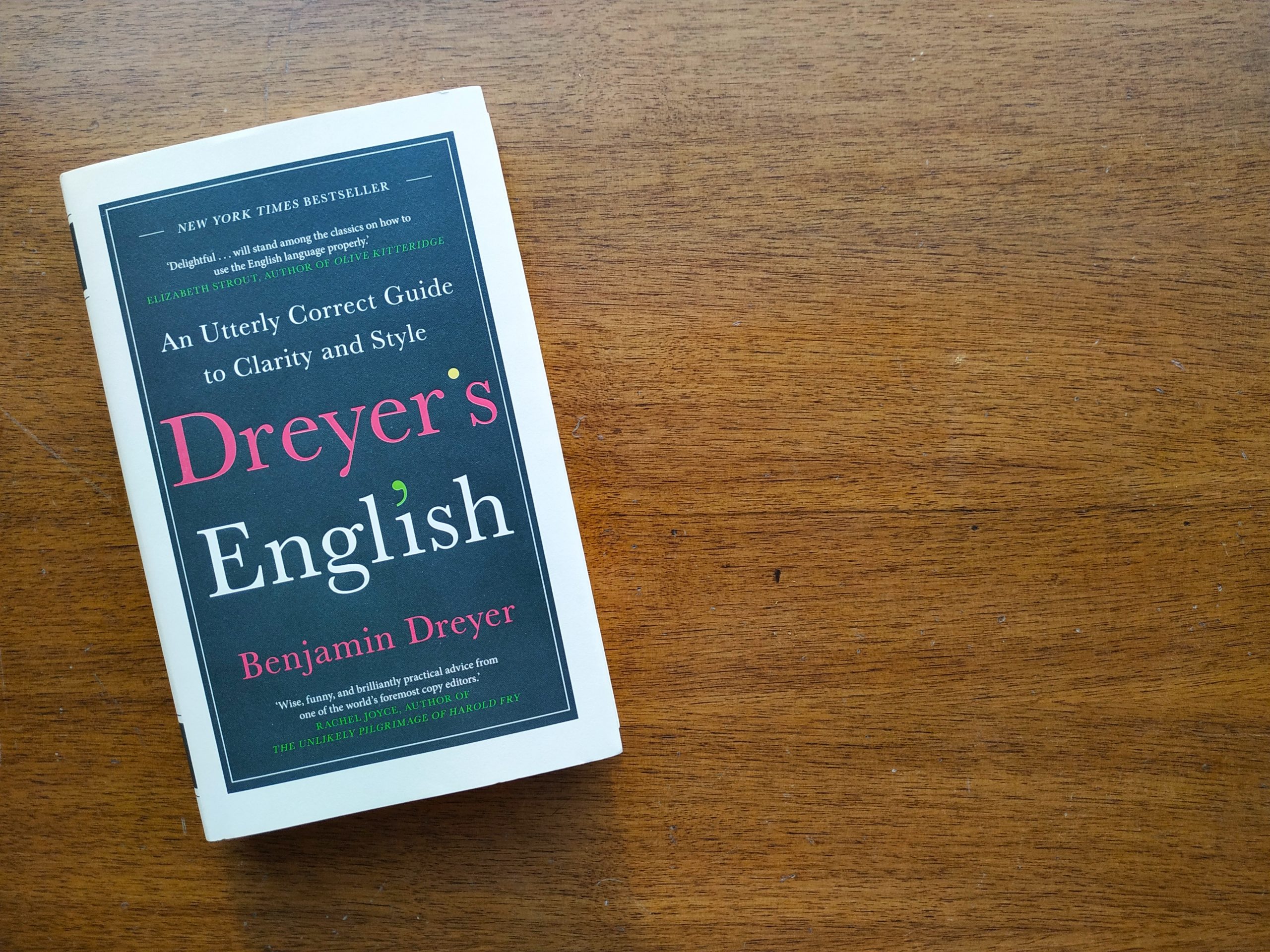

As Random House’s copy chief, Benjamin Dreyer has upheld the standards of the legendary publisher for more than two decades. He is beloved by authors and editors alike—not to mention his followers on social media—for deconstructing the English language with playful erudition.

As authoritative as it is amusing, Dreyer’s English offers lessons on punctuation, from the underloved semicolon to the enigmatic en dash; the rules and nonrules of grammar, including why it’s OK to begin a sentence with “And” or “But” and to confidently split an infinitive; and why it’s best to avoid the doldrums of the Wan Intensifiers and Throat Clearers, including “very,” “rather,” “of course,” and the dreaded “actually.” Dreyer will let you know whether “alright” is all right (sometimes) and even help you brush up on your spelling—though, as he notes, “The problem with mnemonic devices is that I can never remember them.”

Here’s an excerpt from the book!

I am a copy editor. After a piece of writing has been, likely through numerous drafts, developed and revised by the writer and by the person I tend to call the editor editor and deemed essentially finished and complete, my job is to lay my hands on that piece of writing and make it…better.

Cleaner. Clearer. More efficient. Not to rewrite it, not to bully and flatten it into some notion of Correct Prose, whatever that might be, but to burnish and polish it and make it the best possible version of itself that it can be — to make it read even more like itself than it did when I got to work on it.

That is, if I’ve done my job correctly.

On the most basic level, professional-grade copyediting entails making certain that everything on a page ends up spelled properly. (The genius writer who somehow can’t spell is a mythical beast, but everyone mistypes things.) And to remind you of what you already likely know, spellcheck and autocorrect are marvelous accomplices—I never type without one or the other turned on—but they won’t always get you to the word you meant to use. Copyediting also involves shaking loose and rearranging punctuation— I sometimes feel as if I spend half my life prying up commas and the other half tacking them down someplace else—and keeping an eye open for dropped words (“He went to store”) and repeated words (“He went to the the store”) and other glitches that can take root during writing and revision. There are also the rudiments of grammar to be minded, certainly—applied more formally for some writing, less formally for other writing.

Beyond this is where copyediting can elevate itself from what sounds like something a passably sophisticated piece of software should be able to accomplish—it can’t, not for style, not for grammar (even if it thinks it can), and not even for spelling (more on spelling, much more on spelling, later)—to a true craft. On a good day, it achieves something between a really thorough teeth cleaning—as a writer once described it to me—and a whiz-bang magic act.

Which reminds me of a story.

A number of years ago I was invited to a party at the home of a novelist whose book I’d worked on. It was a blazingly hot summer afternoon, and there were perhaps more people in attendance than the little walled-in garden of this swank Upper East Side townhouse could comfortably accommodate. As the novelist’s husband was a legendary theater and film director, there were in attendance more than a few noteworthy actors and actresses, so while sweating profusely I was also getting in a lot of happy gawking.

My hostess thoughtfully introduced me to one actress in particular, one of those wonderfully grand theatrical types who seem, onstage, to be eight

feet tall and who turn out, more often than not, to be quite compact, as this one was, and surprisingly lovely and delicate-looking for a woman who’d made her reputation playing, for lack of a better word, dragons.

It seemed that the actress had written a book.

“I’ve written a book,” she informed me. A memoir, as it turned out. “And I must tell you that when I was sent the copyedited manuscript and saw it all covered with scrawls and symbols, I was quite alarmed. ‘No!’ I exclaimed.

‘You don’t understand!’ ”

By this time she’d taken hold of my wrist, and though her grip was light, I didn’t dare to find out what would happen if I attempted to extricate myself from it. “But as I continued to study what my copy editor had done,” she went on, in a whisper that might easily have reached a theater’s uppermost seats had she wanted it to, “I began to understand.” She leaned in close, staring holes into my skull, and I was hopelessly enthralled. “ ‘Tell me more,’ I said.”

Pause for effect.

“Copy editors,” she intoned, and I can still hear every crisp consonant and orotund vowel, all these years later, “are like priests, safeguarding their faith.”

Now, that’s a benediction.

Get your copy of Dreyer’s English today!