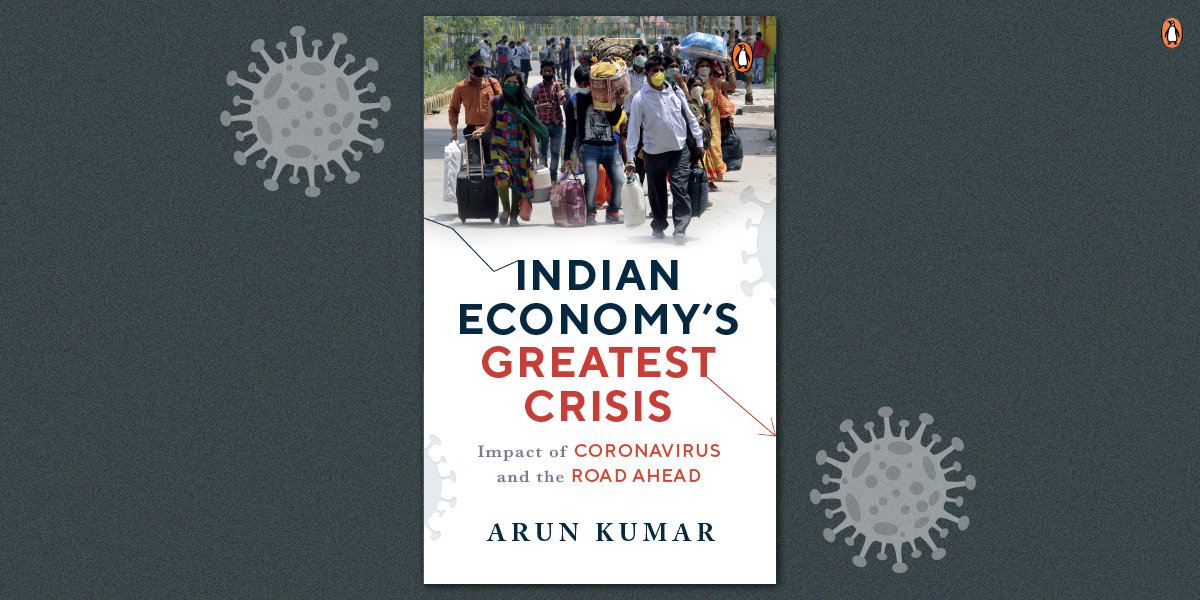

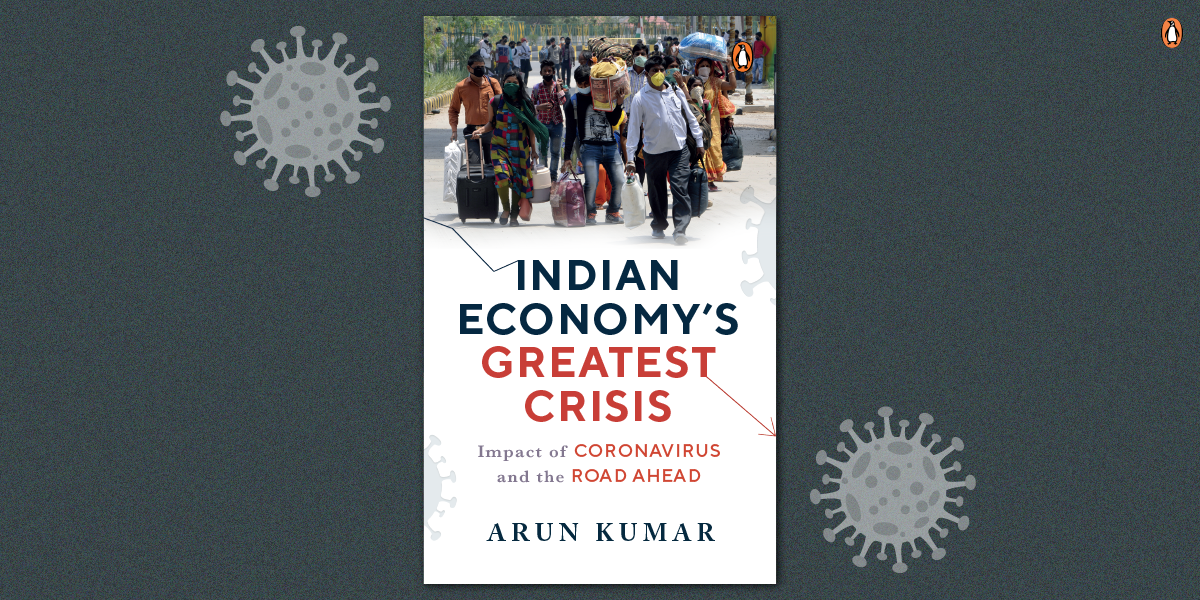

COVID-19 has impacted individual lives and collective communities, making it more urgent than ever to rethink the way our economy runs and the aspects it chooses to focus on. The macroeconomic aspects set the stage for microeconomics, since the latter can be geared according to the former. But macroeconomics can be counter-intuitive and needs to be understood before the other aspects of the economy can be discussed. This is also true in the context of a lockdown. In his book Indian Economy’s Greatest Crisis, Arun Kumar bases his analysis of macroeconomics on the understanding of what happens to variables like incomes, investments, savings, exports, imports and the growth rate of the economy.

In India, the lockdown was substantially loosened June onwards; given the state and spread of the virus in the country, this relaxation came at a time when the pandemic was not brought sufficiently under control. The number of tests was also far below the adequate or ideal number. While some countries have completely controlled the pandemic, it is still unlikely that it will be brought under control globally anytime soon. The economies of different countries have also been affected in different ways under their prospective lockdowns. China was initially reported to have ramped up production after the lockdown ended. In the first quarter of 2020, the rate of growth of the Chinese economy slipped from about +6 per cent in the previous quarter to -6.8 per cent. But the brutal lockdown in the Hubei province ensured that the country could overcome the virus faster. This also ensured the lockdown could be relaxed quickly in the country. As a result, in the second quarter, the economy recovered to +3.2 per cent growth.

According to Arun Kumar, the situation around the world now is actually worse than it was during the depression of the 1930s or during the world wars. A major difference between a situation of war or recession and that of a pandemic is that during wars or recession, while aspects of the economy might be affected adversely in significant ways, production does not stop. This however is not the case during a pandemic. In a lockdown, production cannot take place, so both supply and demand collapse.

Simultaneously, workers get laid off and their incomes fall, and most businesses close down and their profits fall and even turn into losses. The result is that a large number of people lose their incomes and, therefore, demand falls drastically. This is a unique situation and past experiences of dealing with crises have not been useful in predicting what will happen in the future and how one should deal with the present situation. Therefore, according to Kumar, we need a new understanding of and strategy for the macroeconomics of the nation. The macro-variables—output, employment, prices, savings, investments and foreign trade—need to be reformulated and studied in the light of the changed situation.

In such a situation, the economy goes through three stages. From the normal phase, it declines during a lockdown, but even with the easing of lockdown restrictions, it is unlikely that the economy will immediately bounce back to the pre-pandemic phase. Due to continued wage cuts and unemployment, demand is likely to remain low. Many sectors of production will suffer and take long to revive, businesses will fail and the cost of doing business will rise. It is important that India learns from the trajectory of the economies of China and the US. The Indian economy, like the US and Chinese ones, is likely to recover slowly, especially due to its large unorganized sector which has taken a massive hit despite being at the helm of services which can easily be consider essential.

It remains to be seen how recovery and rehabilitation takes place in India, what the role of private businesses will be, and how the government will handle the new few years, which would end up becoming crucial in defining the trajectory of the country in the near future.