We are surrounded by diverse cultures, religions and beliefs. But going through the different mythologies in the world, we often find many similarities. Deities of one kind can be found in various forms among different cultures.

In Hindu Mythology, Yama Raj is regarded as the lord of the death. Similarly, in other cultures the deities of death take a different personification.

Here are 5 different versions of Yama Raj in different cultures.

Santa Muerte

Hades

Dis Pater

Anubis

King Yan

How many of these gods of death did you know of? Tell us.

Tag: Penguin India

Things You Did Not Know About Author and Philanthropist, Sudha Murty

With an ordinary upbringing like most of us, Sudha Murty’s life took extraordinary turns against all odds due to her courage and, determination and will to succeed in life.

Here are a few facts about Sudha Murty that you may have not known before.

Sudha Murty leads with example and shows us that absolutely nothing in life is unachievable, as long as one has the heart to do it.

5 Important Points of the Pioppi Diet

The Pioppi Diet allows red wine, chocolate and the most delicious Italian food and yet helps you to lose weight, de-stress and live a healthier and longer life.

Based on five years of research and drawing on over 100 studies on Pioppi, Dr Aseem Malhotra, a trained cardiologist, has created a plan which is designed to provide readers with the joy and wellbeing of a Mediterranean lifestyle by making small ‘marginal gains’ over a 21-day period.

Here are five key points of the pioppi diet that will help you lose weight and live a healthy lifestyle.

What Should You Eat?

What Should You Avoid?

How much meat should you consume?

How much should you drink?

When should you not eat?

Tell us how did you benefit from the Pioppi Diet.

8 Things You Didn’t Know About Sudeep Nagarkar

Sudeep Nagarkar is the author of eight bestselling novels, including She Swiped Right Into My Heart, It Started With A Friend Request, and All Rights Reserved For You. He is the recipient of the 2013 Youth Achievers’ Award and has been featured on the Forbes India longlist of the most influential celebrities. He also writes for television and has given guest lectures in various renowned institutes and organizations.

His latest novel, Our Story Needs No Filter is set in a socio-political milieu amidst a college campus and explores the dark side of relationships, the pursuit of power and the hypocrisy of the powerful.

Here are 8 little-known things about the bestselling author.

And as they say, the rest is history

Now you know why the stories are so relatable

More time means more books = Yay!

Aww!

That’s how he chills!

Woah!

That’s the secret behind those catchy titles!

Wow!

How many of these facts did you know about Sudeep Nagarkar? Get to know more about his new book, The Secrets We Keep here !

Change Through Tipping Point Leadership

Four Steps to the Tipping Point

- Break through the cognitive hurdle.

To make a compelling case for change, don’t just point at the numbers and demand better ones. Your abstract message won’t stick. Instead, make key managers experience your organization’s problems.

Example: New Yorkers once viewed subways as the most dangerous places in their city. But the New York Transit Police’s senior staff pooh-poohed public fears—because none had ever ridden subways. To shatter their complacency, Bratton required all NYTP officers— himself included—to commute by subway. Seeing the jammed turnstiles, youth gangs, and derelicts, they grasped the need for change—and embraced responsibility for it.

- Sidestep the resource hurdle.

Rather than trimming your ambitions (dooming your company to mediocrity) or fighting for more resources (draining attention from the underlying problems), concentrate current resources on areas most needing change.

Example: Since the majority of subway crimes occurred at only a few stations, Bratton focused manpower there— instead of putting a cop on every subway line, entrance, and exit.

- Jump the motivational hurdle.

To turn a mere strategy into a movement, people must recognize what needs to be done and yearn to do it themselves. But don’t try reforming your whole organization; that’s cumbersome and expensive. Instead, motivate key influencers—persuasive people with multiple connections. Like bowling kingpins hit straight on, they topple all the other pins. Most organizations have several key influencers who share common problems and concerns— making it easy to identify and motivate them.

Example: Bratton put the NYPD’s key influencers— precinct commanders—under a spotlight during semiweekly crime strategy review meetings, where peers and superiors grilled commanders about precinct performance. Results? A culture of performance, accountability, and learning that commanders replicated down the ranks. Also make challenges attainable. Bratton exhorted staff to make NYC’s streets safe “block by block, precinct by precinct, and borough by borough.”

- Knock over the political hurdle.

Even when organizations reach their tipping points, powerful vested interests resist change. Identify and silence key naysayers early by putting a respected senior insider on your top team. Example: At the NYPD, Bratton appointed 20-year veteran cop John Timoney as his number two. Timoney knew the key players and how they played the political game. Early on, he identified likely saboteurs and resisters among top staff—prompting a changing of the guard. Also, silence opposition with indisputable facts. When Bratton proved his proposed crime-reporting system required less than 18 minutes a day, time-crunched precinct commanders adopted it.

This is an excerpt from HBR’s 10 Must Reads (On Change Management). Get your copy here.

Credit: Abhishek Singh

Why Did Gulzar Write ‘Dil Hoom Hoom Kare’ and Not ‘Dil Dhak Dhak Kare’?

“Dil hoom hoom kare” is a famous song from the film Rudaali (1993). The song beautifully captures the longing the woman feels for her lover. In the song, she describes how his love has rejuvenated her and asks him how can she hide the love which the society forbids. The sound ‘hoom hoom’ is supposed to denote the beating of the heart.

Here is why Gulzar used “hoom hoom” to denote the heartbeat against the commonly used “dhak dhak”, as told by him in the book 100 Lyrics.

The heart makes many a demand, but only one sound: ‘dhak-dhak’. Be it the heart of Madhuri Dixit, or of Shammi Kapoor. The language has kept changing with the times but the heart’s sound has always remained the same in our film songs. Particularly Hindi film songs.

Suddenly I came across this Assamese folk song where the sound the heart makes is described as ‘hoom-hoom’. I just loved it. It is much more romantic than ‘dhak-dhak’. There were some apprehensions but I insisted on using the phrase ‘hoom-hoom’ in this song, since the entire tune was based on the same Assamese folk song, only the lines changed according to the situation.

Dil hoom hoom kare (Rudaali, 1993)

Dil hoom hoom kare, ghabraaye

Ghan dham dham kare, darr jaaye

Ek boond kabhi paani ki mori ankhiyon se barsaaye

Dil hoom hoom kare, ghabraaye

Teri jhori daaroon sab sukhe paat jo aaye

Tera chhua laage, meri sukhi daar hariyaaye

Dil hoom hoom kare, ghabraaye

Jis tan ko chhua tune, us tan ko chhupaaoon

Jis man ko laage naina, voh kisko dikhaaoon

O more chandrama, teri chaandni ang jalaaye

Teri oonchi ataari maine pankh liye katwaaye

Dil hoom hoom kare, ghabraaye

Ghan dham dham kare, darr jaaye

Ek boond kabhi paani ki mori ankhiyon se barsaaye

Dil hoom hoom kare, ghabraaye…

—Gulzar

Translation:

The heart rumbles and mumbles

dark clouds of worries roar and thunder

and yet I keep yearning

for even a single drop of tears

to burst forth from my eyes

I know your touch can sprout life

in these shrivelled stumps of my existence

and in this hope I gather and preserve

all the wilted leaves of my life

Your love

that has touched my body

is difficult to hide

but your touch

that has impinged itself on my soul—

how do I bare it to you?

You are my moon, and yet

your soothing rays scorch my skin

your perch is high

and my wings freshly clipped

the heart rumbles and mumbles . . .

—Translated by Sunjoy Shekhar

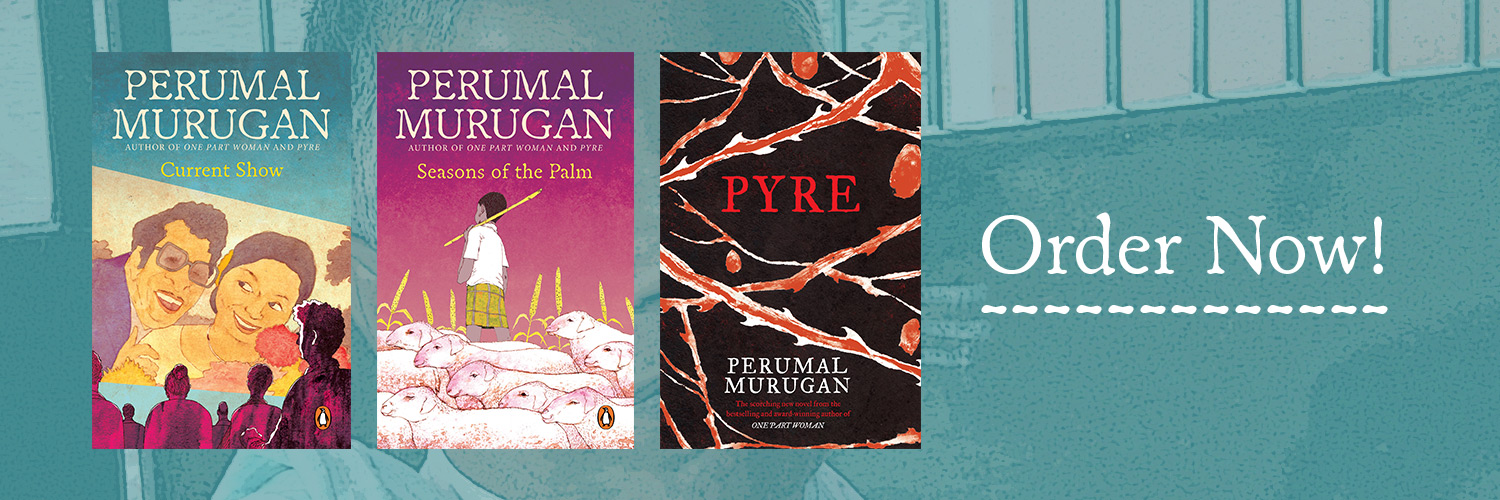

Forsaken Nests —Perumal Murugan

Perumal Murugan is one of the well-known names of Tamil literature. He has garnered both critical acclaim and commercial success on his writings. Many of his writings have been translated in English and have won accolades. His book ‘Seasons of the Palm’ was shortlisted for the Kiriyama Award in 2005.

Murugan, in this piece tells us what pushed him to become a writer.

My family background could not have been the reason for my becoming a writer. I was a first-generation learner. Both my parents, and their forefathers, were illiterate. After a few years of school, I taught my father how to sign. Signing, for him, meant writing his name. He would write each letter very slowly, leaving a playground of space between two letters. At first he did not know how to pronounce these letters. He took months to learn. He felt it would be beneath the dignity of his school-going sons if he were to remain an illiterate, and so he deeply desired to wipe away that shame with just his signature.

The first time he signed his name was on my report card. That day, his face shone brightly with pride. He never asked about my marks or my ranking. For him, the happiness of signing alone would suffice. My brother would forge my father’s signature, but I did not have that kind of courage. We used to call our father’s handwriting ‘hen scribbles’—like the footprints of hens that pitted the ground when they wandered about, without any discernible form or pattern. To this day, one such signature of my father’s is preserved in my tenth-standard register.

I have never had occasion to regret my being born in an illiterate family. Rather, it was an advantage. I enjoyed absolute freedom as far as my education was concerned. I was free to study; I was also free not to study. No one asked me why I studied Tamil often or told me to study mathematics instead. I alone decided the standard till which I would study. While selecting a field of study of my interest, there was no interference. Nothing can equal the joy one feels at the freedom to make one’s own decisions when young. And because I was born to unlettered parents, I enjoyed the peak of such happiness.

After completing my tenth standard, I myself decided on the branch of study I would pursue in the eleventh standard. Though I had secured more than 80 per cent in the core subjects, I opted to study Tamil literature instead of pursuing science or a technical education. My father willingly accompanied me wherever I wanted to go. If anyone asked why I wasn’t studying something else, he would simply say, ‘It’s his choice.’ This being my ‘educational background’, I cannot ascribe my interest in writing to any of my family members, including my grandparents and parents. I myself struggled and learnt to swim in the great flood. And that happiness still lingers in me today.

How the vocation of writing possessed me can be traced to my childhood. There were not many houses in the place where my family lived. Our household was just one among four on a dry, rain-fed stretch of land called ‘Mettukkaadu’. Unlike in other places, farming in the Kongu region demands more than just a few hours of work and a supervisory visit to the field once in a while. In fact, one had to struggle on the land along with the cattle, night and day. Hence families lived in single tenements on their farms. Along with our grandparents as well as two paternal uncles, we numbered four families in all, and we lived close to each other. Some other houses were also there, scattered in the distance.

I was the youngest boy among the families residing there. Those born after me were all girls. There were no playmates of my age. The difference in ages between the older boys and myself was such that I had to call them anna (elder brother) or mama (uncle). A boy playing with girls would be branded as girly and, in any case, boys looked down upon the games of girls. Hence I had to invent games and play them all by myself. I had to imagine playing and conversing with many people, and I even role-played those other people. I had a lot of uninhabited open space at my disposal. Otherwise I would withdraw into myself like a snail if anyone came near me. I barely spoke in public. I was very quiet, a good boy who did not know of mischief.

But in my lonely private terrain I was an adventurer doing all kinds of things. A circular rock in the middle of the farmlands became my regular playground. When the crops stood high and tall around me, I grew more enthusiastic about my private world. For instance, I very much liked the oyilattom—a folk dance staged during temple festivals. Of course, in the middle of a crowd, my body would freeze up; no force could loosen it. But it would become elastic once I reached the rock. The little sparrows living amid the millet crops and the big birds in the sky would move away, either in awe or in fear. However, one day, while I was dancing in my haven, a tree-climber scaling a palm tree in the vicinity happened to witness my antics. In no time he spread the word about my dancing. After that, I could not show my face in public. From then on, the rock was abandoned. That is just how bashful I was.

An unbridgeable solitude and the fictional world that I created in my private space together have propelled me towards writing. Apart from my textbooks, the magazine Rani was the only book that I got hold of by chance. ‘Kurangu Kusala’ and the children’s segment were the sections I really enjoyed. I started composing verses in line with those in the children’s segment. I sent those songs—rhyming ‘Little, little cat; beautiful cat’—to a radio station a few years later. Most of them found a place in the programme Manimalar broadcast by the Trichy Radio Station. The station would not announce in advance whose songs would be aired so I could never be sure whether my rhymes would be broadcast. And if they were aired, I had no one to share the news with. I did not reveal any of this to others for fear of being ridiculed. But these broadcasts boosted my confidence and eventually helped kindle my desire to publish.

I also had a habit of writing long stories modelled on the children’s series ‘The Secret of the Magical Mountain’ and ‘The Princess of the Hill Country’ that were published in Rani. Tunnels figured prominently in my stories. I loved the image of a shy, fearful person walking through dark tunnels all alone. I would imagine a variety of tunnels; myriad figures would appear as stumbling blocks on the way; those things were dear to my heart.

This was how I came into the world of writing. Even at a young age I could perceive writing to be a way of expressing myself. Still, I have been known as a writer in public only these twenty-five years. If I were to count my published works, there are ten novels, four collections of short stories and four anthologies of poetry. I have compiled a dictionary on the local dialect. Some collections of essays have been published; some others compiled. If all my essays get compiled, then there might be some more books.

One who journeys through my works may happen to identify certain common features. I think most of these would relate to my childhood attitude. When I take a step back and view my work from a distance, I discern that by presenting an observation that has occurred to me, perhaps I could give readers an idea of my childhood. For instance, references to the house are made here and there in my works. But the reader cannot reconstruct the house out of these references. My works don’t have elaborate descriptions of the house, nor are the house and its parts at the centre of the scheme of things. All that my writings needed was the expansive open space. The house as an entity is not suited to fill in the open space. Rather, the house could be seen as an eyesore troubling that space. This attitude can be seen at its peak in my novel Koolamadhari, where the expanse is all pervasive. My childhood idea of the house was only that of a granary—used to store the grains for a year’s requirements. Cooking and sleeping were done outside the house. Even the stove used to be outside the house. A portable charcoal oven was used for cooking during the rainy season. Sleeping took place either in the yard or in the goat pens and the mangers. Though I have become accustomed to the middle class way of life, to this day, I like the open space the most.

Birds do not inhabit nests. They build nests, out of necessity, during the reproductive season. They require the protection of the nests for laying and hatching their eggs and till the nestlings spread their wings to fly. Then the nests are abandoned—forsaken on the trees, fallen on the stones, empty holes left behind after the chicks have grown up. I feel as though my childhood dispositions lie embedded in me in the form of such deserted nests. And it feels right to say that my works encompass such nests.

Translated by: V. Premkumar

Get copies of Seasons Of the Palm, Current Show, and Pyre here.

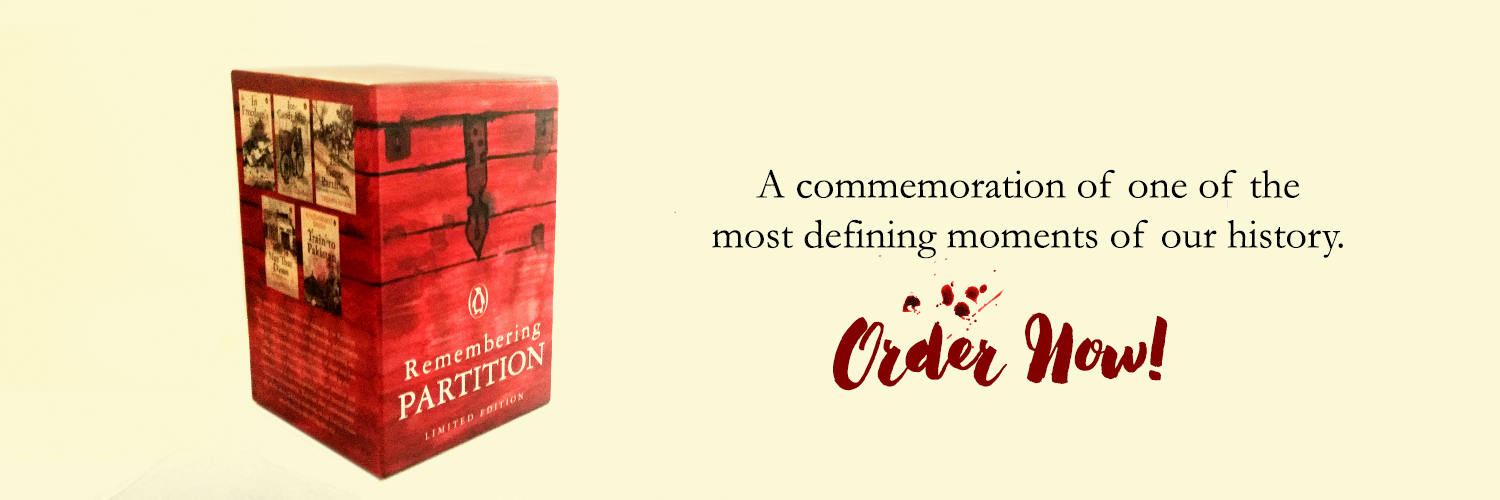

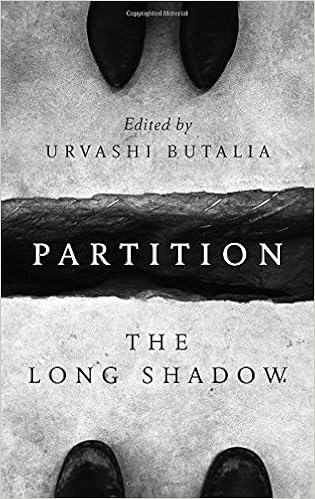

25 Must Reads On the 70th Anniversary of Partition

India’s freedom from the British rule was stained by the horrors of its partition. The reverberations of the event over the last seventy years have been encapsulated in several books, plays, and other forms of media.

Here is a list of 25 books that capture one of the most defining moment of our history.

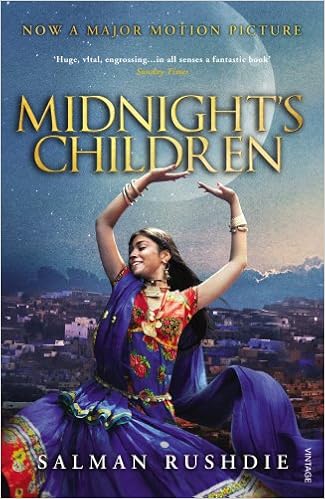

Midnight’s Children

Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie is an epic novel that opens up with a child being born at midnight on 15th August 1947, just at a time when India is achieving Independence from centuries of foreign British colonial rule. Highlighting the relation between father and son and a nation yet in its nascent stage, it is an enchanting family adventure with lots of human drama and shocking summoning.

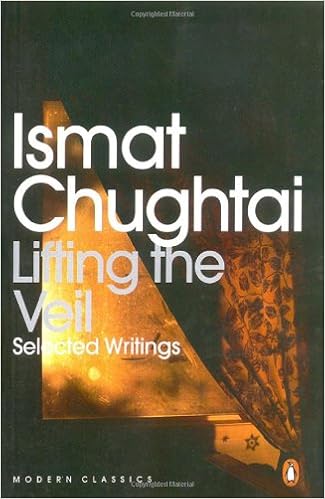

Lifting The Veil

Ismat Chughtai in Lifting the Veil explored female sexuality with unparalleled frankness and examined the political and social mores of her time.

Train to India: Memories of Another Bengal

As a young boy, Maloy Krishna Dhar, made the perilous journey to India from the East Pakistan. The partion in Bengal had its share of tragedy, of lives unmade and lost, but it is relatively less chronicled than events in Punjab. Maloy Krishna Dhar’s Train to India is a graphic and moving account of that turbulent and unforgotten era of Bengal History.

The Shadow Lines

As a young boy, Amitav Ghosh’s narrator in The Shadow Lines travels across time through the tales of those around him, traversing the unreliable planes of memory, unmindful of physical, political and chronological borders. Bits and pieces of stories, both half-remembered and imagined, come together in his mind until he arrives at an intricate, interconnected picture of the world where borders and boundaries mean nothing, mere shadow lines that we draw dividing people and nations.

Midnight’s Furies

Nisid Hajari’s Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition shows how Partition, which has created such a wide gulf between two countries whose people have so much in common, has given birth to global terrorism and dangerous proliferation.

On a backdrop India’s struggle for independence, Laila, an orphaned daughter of a distinguished Muslim family, fights for her own independence from the claustrophobia of a traditional life. With its beautiful evocation of India, its political insight and unsentimental understanding of the human heart, Sunlight on a Broken Column, first published in 1961, is a classic of Muslim life.

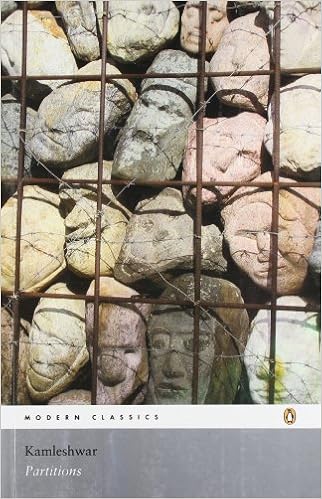

With India’s partition in 1947 as its reference point, the novel presents a limitless canvas against which the most extraordinary trial in the history of mankind runs its course. Kamleshwar’s Kitne Pakistan dared to ask crucial questions about the making and writing of history.

Amritsar to Lahore by Stephen Alter

A sensitive and thoughtful look at the lasting effects of Partition on everyday people, Amritsar to Lahore describes a journey across the contested border between India and Pakistan in 1997, the fiftieth anniversary of Partition. Offering both the perspective of hindsight and a troubling vision of the future, Amritsar to Lahore presents a compelling argument against the impenetrability of boundaries and the tragic legacy of lands divided.

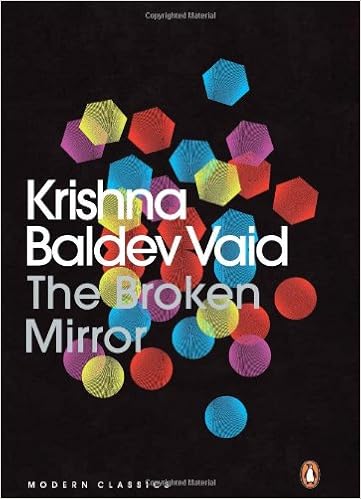

The Broken Mirror by Krishna Baldev Vaid tells the story of Beero and his group of friends against a backdrop of partition of India. Beero’s passage through adolescence is told through a series of eccentric characters. When partition becomes a reality, in a time of terror and carnage, the insane turn out be the only ones sane.

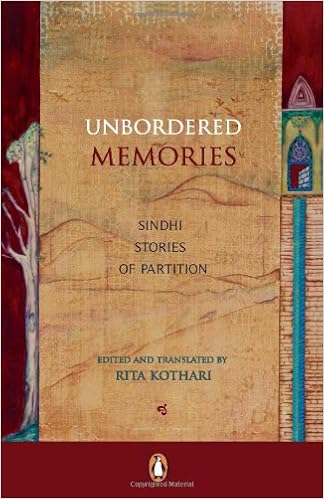

If Partition affected the lives of Sindhi Hindus, it also changed things for the Sindhi Muslims. In Unbordered Memories, Sindhis from India and Pakistan make imaginative entries into each other’s worlds. Many stories in this volume testify to the Sindhi Muslims’ empathy for the world inhabited by the Hindus, and the Indian Sindhis’ solidarity with the turbulence experienced by Pakistani Sindhis.

The Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 left a legacy of hostility and bitterness that has bedevilled relations between India and Pakistan. Reviewing the turbulent history of their past relationship, Radha Kumar analyses the chief obstacles the two countries face in the light of the new opportunities and challenges that the twenty-first century presents.

Bitter Fruit: The Very Best of Saadat Hasan Manto

Manto’s stories were mostly written against the backdrop of the Partition. Bitter Fruit presents the best collection of Manto’s writings, from his short stories, plays and sketches, to portraits of cinema artists, a few pieces on himself. Bitter Fruit includes stories like A Wet Afternoon, The Return, A Believer s Version, Toba Tek Singh, Colder than Ice and many others.

Kingdom’s End: Selected Stories

This collection brings together some of Manto’s finest stories, ranging from his chilling recounting of the horrors of Partition to his portrayal of the underworld. Powerful and deeply moving, these stories remain as relevant today as they were first published.

Mottled Dawn by Saadat Hasan Manto is a collection of stories based on the India-Pakistan partition. The stories written around 1947 put forward the most tragic events in the history of the subcontinent.

Saadat Hasan Manto’s stories are vivid, dangerous and troubling and they slice into the everyday world to reveal its sombre, dark heart. These stories were written from the mid-1930s on, many under the shadow of Partition. No Indian writer since has quite managed to capture the underbelly of Indian life with as much sympathy and colour.

Written by the first President of India, India Divided traces the origins and growth of the Hindu–Muslim conflict, gives the summary of the several schemes for the partition of India which were put forth, and points out the essential ambiguity of the Lahore Resolution. Finally, it concludes that the solution for the Hindu–Muslim issue should be sought in the formation of a secular state, with cultural autonomy for the different groups that make up the nation.

Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage That Shook India Sheela Reddy in Mr and Mrs Jinnah brings forth the marriage that convulsed the Indian society with a sympathetic, discerning eye. A product of intensive and meticulous research in Delhi, Bombay and Karachi, and based on first-person accounts and sources, Reddy sheds light on how the politics of the time affected the marital life of misunderstood Jinnah and wistful Ruttie.

Sheela Reddy in Mr and Mrs Jinnah brings forth the marriage that convulsed the Indian society with a sympathetic, discerning eye. A product of intensive and meticulous research in Delhi, Bombay and Karachi, and based on first-person accounts and sources, Reddy sheds light on how the politics of the time affected the marital life of misunderstood Jinnah and wistful Ruttie.

A timeless classic about the Partition of India, Tamas is also a chilling reminder of the consequences of religious intolerance and communal prejudice.

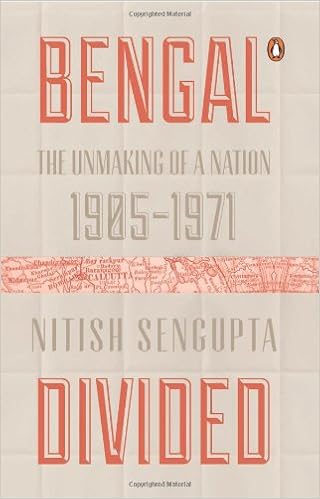

Bengal Divided: The Unmaking of a Nation (1905-1971)

In 1905, all of Bengal rose in uproar because the British had partitioned the state. Yet in 1947, the same people insisted on a partition along communal lines. Exploring the roots of alienation of the two communities, Nitish Sengupta peels off the layers of events in this pivotal period in Bengal’s history, casting new light on the roles of figures such as Chittaranjan Das, Subhas Chandra Bose, Nazrul Islam, Fazlul Huq, H.S. Suhrawardy and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee.

In Mukul Kesavan’s Looking Through Glass, a young photographer on a train to Lucknow suddenly finds himself in the deep end of 1942. His hindsight tells him that Partition will destroy this world. And in his desperate struggles to avert the inevitable, we discover, often with an almost unbearable poignancy, how the possibilities in India’s past were squandered, some wantonly, others accidentally.

A collection of two novellas—Regret and Out of Sight, the stories skilfully evoke the long shadow cast by the violence of Partition. While Regret brilliantly recreates a childhood shattered by the Partition of India in 1947, Out of Sight recounts the story of Ismail, who narrowly escaped the carnage of 1947 in his youth. Now, looking back on his life and despairing of the sudden resurgence of sectarian violence in Pakistan.

Memories Of Madness: Stories Of 1947

The tragic legacy of Partition haunts the subcontinent even today. Memories of Madness brings together works by three leading writers who witnessed the insanity of those months—Khushwant Singh, Saadat Hasan Manto, and Bhisham Sahni. As moving as they are disturbing, the stories in this volume are of immense relevance in these times, for they constitute a chilling reminder of the consequences of communal politics.

The Other Side of Silence

Pieced together from oral narratives and testimonies, in many cases from women, children and dalits— marginal voices never heard before— and supplemented by documents, reports, diaries, memoirs and parliamentary records, this is a moving, personal chronicle of Partition that places people, instead of grand politics, at the centre.

The dark legacies of partition have cast a long shadow on the lives of people of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The borders that were drawn in 1947, and redrawn in 1971, divided not only nations and histories but also families and friends. The essays in this volume explore new ground in Partition research, looking into areas such as art, literature, migration, and notions of ‘foreignness’ and ‘belonging’.

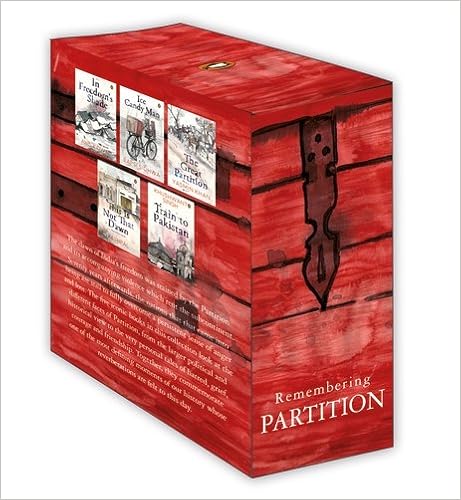

Remembering Partition: Limited Edition

The Remembering Partition Box Set is a collection of five iconic books which look at the different faces of partition, from the larger political and historical view to the very personal tales of hatred, grief, courage and friendship.

On the 70th anniversary of partition, which book are you picking?

7 Quotes by Famous Authors That Will Make You Cherish Freedom

What do we understand by the term ‘freedom’? The liberty to make our choices, the liberty to lead the life we want, the liberty to speak the language we choose. But does freedom mean the same thing to everyone?

Here are 7 quotes by famous writers with different meanings to ‘freedom’.

Tell us which idea of freedom do you agree with!

5 Books You Must Read in Remembrance of the Partition

The pain of partition accompanied the joy of freedom for India. Even after seventy years, the horrors of violence still haunt the two countries.

The Remembering Partition Box Set is a collection of five iconic books which look at the different faces of partition, from the larger political and historical view to the very personal tales of hatred, grief, courage and friendship.

Here are the five books that commemorates one of the most defining moments of our history.

Train to Pakistan by Khushwant Singh

Ice-Candy-Man by Bapsi Sidhwa

This Is Not That Dawn by Yashpal

The Great Partition by Yasmin Khan

In Freedom’s Shade by Anis Kidwai

Pick up this collection and re-visit the heart-rending event.