A former journalist, Paula Hawkins started writing romcom fiction under the name Amy Silver, writing four novels including Confessions of a Reluctant Recessionista.

After the bestseller The Girl on the Train, Hawkins returns with Into the Water, a twisting read that hinges on the deceptiveness of emotion and memory.

Here are a few quotes from The Girl on the Train and Into the Water, that’ll enthrall any reader.

Enthralled yet? Let us know what you think of Paula Hawkins’ works in the comments below.

Tag: Penguin India

5 Lesser-Known Books by Ruskin Bond that You Must Read

Ruskin Bond has written a string of unforgettable tales – stories about nature and animals, and the bond formed between humans and the wild. As we celebrate Ruskin Bond’s 83rd birthday, here are some of his lesser-known great writings.

Vagrants in the Valley

This book catches up with our favourite Rusty as he plunges not just into the cold pools of Dehra but into an exciting new life, dipping his toes into adulthood. At once, thrilling and nostalgic, this heart-warming sequel is Rusty at his best as he navigates the tightrope between dreams and reality, all the time maintaining a glorious sense of hope.

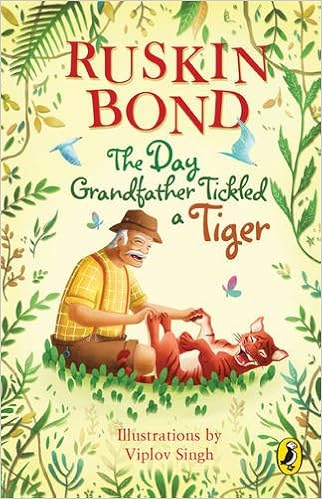

The Day Grandfather Tickled a Tiger

Grandfather had brought home Timothy, the little tiger cub, from the forests of the Shivaliks. Timothy grew up to be a friendly tiger, with a monkey and a mongrel for company. But some strange circumstances lead grandfather to take Timothy away to a zoo. Will they ever meet again? This a heart-warming story of love and friendship!

Rusty Runs Away

Rusty’s world is turned topsy-turvy when his father and grandmother pass away in quick succession. The twelve-year-old is sent away to boarding school by his guardian, Mr Harrison. Restlessness, coupled with an ambition to travel the world, compels him to run away from his rather humdrum life at school. But the plan fails, and he is soon back in Dehra, with his strict guardian. Rusty is now seventeen. He rebels and leaves home again, this time for good.

The Tree Lover

His mesmerizing descriptions of nature and his wonderful way with words—this is Ruskin Bond at his finest. Read on as Rusty tells the story of his grandfather’s relationship with the trees around him, who’s convinced that they love him back with as much tenderness as he loves them.

Dust on the Mountain

When twelve-year-old Bisnu decides to go to Mussoorie to earn for his family, he has no idea how dangerous and lonely life in a town can be for a boy on his own. As he sets out to work on the limestone quarries, with the choking dust enveloping the beautiful mountain air, he finds that he longs for his little village in the Himalayas.

Which is your favourite Ruskin Bond story? Tell us as we celebrate the bond of stories with Mr Bond!

10 Lessons from Lilly Singh’s Book, “How To Be A Bawse”

Lilly Singh is a multi-faceted comedian, entertainer and now an international bestselling author. In her book, HOW TO BE A BAWSE: A Guide to Conquering Life, Lilly teaches readers how to be their own bawse, a person who exudes confidence and reaches goals. Inspired by hilarious and honest stories from Lilly’s own experiences, this book proves that there are no shortcuts to success and becoming a bawse requires handwork and dedication.

Here are 10 of our favorite lessons from Lilly (aka Superwoman) in How To Be A Bawse:

Tell us how are you conquering life.

The Boy Who Loved — An Exclusive Excerpt

1 January 1999

Hey Raghu Ganguly (that’s me),

I am finally putting pen to paper. The scrunch of the sheets against the fanged nib, the slow absorption of the ink, seeing these unusually curved letters, is definitely satisfying; I’m not sure if writing journal entries to myself like a schizophrenic is the answer I’m looking for. But I have got to try. My head’s dizzy from riding on the sinusoidal wave that has been my life for the last two years. On most days I look for ways to die—the highest building around my house, the sharpest knife in the kitchen, the nearest railway station, a chemist shop that would unquestioningly sell twenty or more sleeping pills to a sixteen-year-old, a packet of rat poison—and on some days I just want to be scolded by Maa–Baba for not acing the mathematics exam, tell Dada how I will beat his IIT score by a mile, or be laughed at for forgetting to take the change from the bania’s shop.

I’m Raghu and I have been lying to myself and everyone around me for precisely two years now. Two years since my best friend of four years died, one whose friendship I thought would outlive the two of us, engraved forever in the space– time continuum. But, as I have realized, nothing lasts forever. Now lying to others is fine, everyone does that and it’s healthy and advisable—how else are you going to survive the suffering in this cruel, cruel world? But lying to yourself? That shit’s hard, that will change you, and that’s why I made the resolution to start writing a journal on the first of this month, what with the start of a new year and all, the last of this century.

I must admit I have been dilly-dallying for a while now and not without reason. It’s hard to hide things in this house with Maa’s sensitive nose never failing to sniff out anything Dada, Baba or I have tried to keep from her. If I were one of those kids who live in palatial houses with staircases and driveways I would have plenty of places to hide this journal, but since I am not, it will have to rest in the loft behind the broken toaster, the defunct Singer sewing machine and the empty suitcases.

So Raghu, let’s not lie to ourselves any longer, shall we? Let’s say the truth, the cold, hard truth and nothing else, and see if that helps us to survive the darkness. If this doesn’t work and I lose, checking out of this life is not hard. It’s just a seven-storey drop from the roof top, a quick slice of the wrist, a slip on the railway track, a playful ingestion of pills or the accidental consumption of rat poison away. But let’s try and focus on the good.

Durga. Durga.

12 January 1999

Today was my first day at the new school, just two months before the start of the tenth-standard board exams. Why Maa– Baba chose to change my school in what’s said to be one of the most crucial year in anyone’s academic life is amusing to say the least—my friendlessness.

‘If you don’t make friends now, then when will you?’ Maa said. They thought the lack of friends in my life was my school’s problem and had nothing to do with the fact that my friend had been mysteriously found dead, his body floating in the still waters of the school swimming pool. He was last seen with me. At least that’s what my classmates believe and say. Only I know the truth.

When Dada woke me up this morning, hair parted and sculpted to perfection with Brylcreem, teeth sparkling, talcum splotches on his neck, he was grinning from ear to ear. Unlike me he doesn’t have to pretend to be happy. Isn’t smiling too much a sign of madness? He had shown the first symptoms when he picked a private-sector software job over a government position in a Public Sector. Undertaking which would have guaranteed a lifetime of unaccountability. Dada may be an IITian but he’s not the smarter one of us.

‘Are you excited about the new school, Raghu? New uniform, new people, new everything? Of course you’re excited! I never quite liked your old school. You will make new friends here,’ said Dada with a sense of happiness I didn’t feel. ‘Sure. If they don’t smell the stench of death on me.’ ‘Oh, stop it. It’s been what? Over two years? You know how upset Maa–Baba get,’ said Dada. ‘Trust me, you will love your new school! And don’t talk about Sami at the breakfast table.’ ‘I was joking, Dada. Of course I am excited!’ I said, mimicking his happiness.

Dada falls for these lies easily because he wants to believe them. Like I believed Maa–Baba when they once told me, ‘We really liked Sami. He’s a nice boy.’ Sami, the dead boy, was never liked by Maa–Baba. For Baba it was enough that his parents had chosen to give the boy a Muslim name. Maa had more valid concerns like his poor academic performance, him getting caught with cigarettes in his bag, and Sami’s brother being a school dropout. Despite all the love they showered on me in the first few months after Sami’s death, I thought I saw what could only be described as relief that Sami, the bad influence, was no longer around. Now they use his name to their advantage. ‘Sami would want you to make new friends,’ they would say. I let Maa feed me in the morning. It started a few days after Sami’s death and has stuck ever since.

Maa’s love for me on any given day is easily discernible from the size of the morsels she shoves into my mouth. Today the rice balls and mashed potatoes were humungous. She watched me chew like I was living art. And I ate because I believe the easiest way to fool anyone into not looking inside and finding that throbbing mass of sadness is to ingest food. A person who eats well is not truly sad. While we ate, Baba lamented the pathetic fielding placement of the Indian team and India’s questionable foreign policy simultaneously.

‘These bloody Musalmans, these filthy Pakistanis! They shoot our soldiers…

Devdutt Pattanaik on Mothers

Mothers have been an important mainstay in epics, folk tales and mythologies for generations. Today, as we celebrate Mother’s Day, here is an exclusive excerpt on mothers from Devdutt’s Devlok 2.

A mother gives birth to a child. But did god give birth to the mother or did a mother give birth to god?

As interesting as the question is, the answer too is not simple. In a temple, the space where a god’s image is kept is known as garbha griha; that is, god is residing inside the garbha. Garbha means womb. Whose womb is this? A temple itself has been seen as a woman, a mother. Spiritually, Prakriti is everyone’s mother. Prakriti has given birth to sanskriti (culture). God’s mother is also Prakriti.

The Rigveda has this interesting sentence that Daksha gave birth to Aditi and Aditi gave birth to Daksha; that is, the father created the mother and the mother created the father. When you go way back in the past, the division between father and mother collapses. With god, this concept does not hold because god is swayambhu—he has given birth to himself; he is his own mother. Two words are used often in the Puranas – Yonija (born of the womb) and Swayambhu (who gives birth to self). God is always swayambhu, but his avatars are yonija; they experience birth and death. For instance, Ram is an avatar, so he is born and dies. He has a mother, Kaushalya. Krishna, likewise, has a mother, Devaki. Shiva is swayambhu.

In Tantra parampara, where goddesses are given a lot of importance, the stories and folk tales speak of how in the beginning of the world there was only a devi/Prakriti called Adi Maya Shakti. She gave birth to three eggs from which were born Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. She is therefore called Triamba (one who gave birth to three children). This does not happen in puranic stories. In Shakt parampara, god does have a mother. In Vaishnav parampara, god gives birth to himself; and he creates the world and its creatures from himself. In Shaiva parampara, Shiva gives birth to himself; he is swayambhu, doesn’t have a mother, but gives birth to all mothers.

Devi is sometimes called a kumari (virgin) and sometimes mata (mother). How is that?

Christianity has a concept of the virgin mother who is Jesus’s mother. The word kumari, in India and in the world, does no necessarily mean virgin. It means a woman who is independent, who has no husband, and no man has a right over her. She has no ties and is completely liberated. So she is both mata and kumari, that is, an independent mother. Her hair is always depicted untied, to symbolize her freedom. No one can have dominance over Prakriti.

In Vaishnodevi or Kal Bhairav temples, the story is that of Bhairav wanting to have a relationship with the goddess; the goddess refused and cut off his head. ‘You cannot control me.’ Kal Bhairav then becomes her guard. In another story, when Brahma’s fifth head wanted a right over her, Bhairav cut off his head. Such are the violent stories associated with kumari.

The symbolic meaning could be that man’s ego prevents a devi from becoming a kumari, which is why he gets cursed or gets his head cut off. These are spiritual, metaphysical topics.

Shiva was swayambhu, but who was his son Karitkeya’s mother—Parvati or Ganga?

In Shiv Puran, the story is that after their marriage, Shiva says he has no need for a child. He says, ‘I am swayambhu, anadi, anant, without beginning or end; I will never die. So why do I need children?’ Devi says, ‘But I want children; I want to be a mother.’ An interesting conflict arises here. When Shiva is about to offer his seed, all gods and goddesses say that Shiva’s seed cannot be accommodated in just one womb; it should be placed in many wombs. The story goes that his seed is so hot that no one can touch it. First is is given to Vayu, wind, in the beliefe that he’ll be able to cool it down, but he fails. Vayu gives the seed to Agni, fire, who too cannot hold it. He passes it on to Ganga and her waters starts boiling. The reed forests (Sara-vana) near the river start burning. From the ash of those reeds, a child emerges. In some stories, it is six children who emerge. As the infants start crying, Krittika nakshatra, constellation of six stars, descend from the sky as the childrens’ mothers and feed them milk. Finally, Gauri, Shiva’s wife, joins the six children together. That child is Kartikeya, also called Shanmukha, or one with six heads.

The question arises, the father of the child is Shiva, but who is the mother? Vayu, Agni, Ganga, Sharavan, Krittika, Parvati all stake a claim. So, he has many mothers. Shiva’s seed has thus gone to many yonis; it shows that the child is so powerful, he cannot be born of just one womb. Kartik means son of Krittika. In the south, he is called Sharavanan, son of Sharavan. In images, he is sometimes shown along with six or seven matrika, mothers.

What is Ganesh’s story? Who is his mother?

In stories, although Shakti wants to become a mother, the gods don’t want her to give birth in the normal way. If the child is born from her yoni, it’ll be so powerful that it will defeat Indra, the king of the gods. So, Shiv-Shakti’s children are not born from Parvati’s yoni. Kartikeya is born of Shiva’s seed, from many yonis. Ganesh is born from the scrapings of Parvati’s body. Again, he is ayonija.

The story is that Parvati goes to Shiva, asking him to give her a child. He says he is not interested as he’s immortal. She tells him she’ll make it herself; she’s the goddess, after all. She first collects the scrapings (mull) of her skin, mixed with the applied chandan and haldi. Then she makes a doll of it and gives it life. In Vamana Purana, it is said the child’s name ‘Vinayak’ comes from ‘bina nayak’ (without a man); there are other stories about the word’s origin too. Shiva does not like the way Parvati has birthed her child, as he cannot recognize her image in it, so he cuts off its head. Parvati starts weeping, and insists he bring back the child to life. So Shiva gives him an elephant head and that’s how Ganesh is born. Again, it is ayonija.

In the Mahabharat, we see many ambitious mothers who want their sons to be king.

In the Puranas, the stories have more of a spiritual, intellectual concern, while in the Ramyan and Mahabharat, the focus is on wealth and property. For this reason, the men go to war, and the women want their sons to grow up and be victorious. This is presented in a fascinating way in the Mahabharata. When Shantanu wants to marry Satyavati, she first attaches a condition that her son inherit Shantanu’s kingdom. She claims she is securing her child’s future. Is that the real reason or does she want the high position of a rajmata (queen mother)?

There is also a competition between Gandhari, Kunti and Madri. When Gandhari is pregnant, she hears that Kunti has given birth to a son. Although Gandhari was pregnant from before, Kunti used her mantra to have Yudhisthir without the nine-month period. Gandhari gets so upset, she beats her belly with a stick. The mass that emerges from her belly is cold as iron. When Vyas creates 100 children from this mass, Gandhari is happy, because now she has more children than Kunti. Kunti begets two more children and uses up the power of her mantra. She gives the mantra to Madri who uses it once and calls Ashvin Kumar and gets the twins, Nakul and Sahdev. Pandu asks Kunti to let Madri use the mantra once more as she herself had used it thrice, but Kunti refuses. She fears that if Madri were to produce twins again, she’d have more children, and therefore more importance, than her. In the Mahabharat, this rivalry has been subtly depicted.

What about the mothers in the Ramayana?

Kaikeyi’s story is the most well known. When she had saved Dashrath’s life during a dev-asura battle, he had promised her two boons. The day before his eldest son, Ram’s, coronation, she throws a tantrum and demands her boons. She asks that Bharat be made king instead of his first-born Ram, and that he send Ram into vanvas (life in the forest) for 14 years. Ram’s mother, Kaushalya, is pained and asks Kaikeyi why she had to be so cruel to a son who’d treated her like his own mother.

An interesting aspect of this story is that when Dashrath marries Kaikeyi, he does not have any children. The astrologer says that Kaikeyi will definitely have a son. At that time, Dashrath promises her that her son would become king. So, in a way, Kaikeyi is only asking for what is rightfully her due. It’s like a court case, a settling of an agreement, where the lines are not clear. Whether Kaikeyi is ambitious or merely asking for her right is hard to say.

Krishna is called Devakinandan and Yashodanandan. Who was his mother?

There are some who believe that Krishna is not an avatar (of Vishnu’s) but himself an avatari—from whom avatars emerge. Others see him as an avatar. But he is born from Devaki’s womb, so he is yonija and experiences death. Mausala Parva in Mahabharat describes Krishna’s death. He is born from Devaki’s womb in Mathura, but is raised by Yashoda in Gokul. So he has two mothers – birth/blood mother and milk mother.

In folk songs, Krishna is asked who his real mother is—Devaki who has birthed him or Yashoda who has raised him? Krishna replies, do you think my heart is so small that it cannot contain more than one mother? I can handle both. But the question is who has the maternal right over him? Who is to answer that—it’s a complex world. The story suggests that relationships are not built by blood alone. Another aspect is that Devaki is a princess, while Yashoda is a milkmaid. So Krishna’s claim that both are his mothers shows that he has a relationship with the palace dwellers as well as cowherds, with the city as well as the village. He is large-hearted and this is why Krishna is associated with love.

In Puranas, is there a story of single mothers?

Bhagwat Puran has a story of Devahuti whose husband is Kardam rishi who says he doesn’t really want to have children, but has been told by his ancestors that he won’t achieve moksha (liberation from life and death) until he has children. But he doesn’t want any part in raising that child. Devahuti agrees to raise the child alone, and the child grows up to be Kapil muni who develops the Sankhya philosophy. It is also well known that Sita raises Luv and Kush on her own. Shakuntala too raises her son Bharat by herself in the forest, without the support of her husband.

Is there a story in our Puranas where a father plays the role of a mother?

When apsaras have children, they abandon them. Shakuntala’s mother Menaka had abandoned her in the jungle, and Shakuntala was raised by Kanva rishi who is like a single father. When Sita goes back to her mother, and disappears inside earth, she leaves her children behind with Ram who becomes a single father.

This is an excerpt from Devdutt Patnaik’s Devlok 2.

First Stories: A Mother’s Day Tribute to the First Storyteller of Our Lives

A mother is usually our first friend in this world and our first storyteller! From bedtime stories to explaining the world to us, mothers fulfil our most passionate curiosity – the desire to be told stories.

And we loved her most.

We held her hands and walked to the bookshop – ogling at the colourful editions, leafing through them, and falling in love with the smell of new books – for the first time ever!

Her smile did hug us!

Her smile did hug us!

Sometimes, when we wouldn’t eat, she would distract us with the world of stories, nourishing us: body and soul

Just like the Runaway Bunny’s mum.

Just like the Runaway Bunny’s mum.

And when night befell, we would snuggle next to her with a good book. Her storytelling voice gently guiding us into our world of dreams!

Bliss.

Bliss.

This Mother’s Day, join us in celebrating the first storyteller of our lives.

Do you remember the first story you ever heard from your mum that you would like to share? We would love to know!

*

5 Badass Mothers in Literature

To call mothers a superhero will be an understatement (we are pretty sure they wear an invisible cape). Just like our real-life moms, mothers in literature also pull of some great tasks with breathtaking ease. Whether they are trying to protect the protagonists or just do a great job at raising them, we can’t help but look up to them.

So, here are five badass mothers:

Hester Prynne, The Scarlet Letter

Hester Prynne, in 17th century, did what other ladies in that era couldn’t even imagine doing i.e. live an independent life while raising a child on her own. Even though punished by her Puritan neighbours, she refuses to give out the names of her lover and their daughter. Deemed as an outcast then, she’d be considered a heroine today, like many of our moms.

Raksha, The Jungle Book

She is the fiercest mother we know. She cared for Mowgli as much as she did for her cubs. When Shere Khan threatened the pack to give up Mowgli, she proclaimed as his protector. Foster or not, a mother is a mother.

Mariam, A Flight of Pigeons

Mariam is an indomitable lady with a charm. Despite being at Javed Khan’s house in the times of turmoil, she refuses his proposition to marry her daughter Ruth. She does not give into the adversity of her circumstances but takes a chance with faith, saving her daughter’s life in the end.

Rosa Hubermann, The Book Thief

Rosa Hubermann is Liesel’s foster mother who has a “wardrobe build”, sharp tongue and a no-nonsense attitude. She does laundry for the wealthier households to help her family financially. She also never got fazed by anybody, not even Nazis during World War II. She is a mom who uses cuss words to show affection.

Marmee, Little Women

Runs the household by herself, raises four daughters, becomes their counsellor and role model, Marmee did it all. She also teaches them and nurtures them to become strong, inspirational women while keeping each of them true to their individuality. If Marmee isn’t a badass mother, we don’t know who is.

Do you know any more names that should be on this list? Tell us.

Meet Bilal — An Excerpt

Mr Unwin, meet Bilal.

He is the taller of the two who stand under the arch of bougainvillea, the wooden gate open behind them. I am the shorter one, the one who is squinting. That is a temporary squint, and I squinted at the time of being photographed not because of the sun, I was just trying to hide my discomfort at being looked at through a viewfinder. The picture was taken on the first Small Eid after we came to live in Bougainvillea, and I invited him for the feast because I owed him a treat. That is another story, but let me narrate it now because it may not fit anywhere else in this book.

A week after I joined the town school, of which Vappa, Uncle Yazin and Aunt Yasmin were the alumni of, I ran into Bilal on the cliff path. At school we sat on the same bench because we were of the same height, almost, and I willed him to quickly grow a head taller so I would not have to sit next to him any more: he smelled like cashew orchards in springtime and I always associated the smell of cashew flowers with death. But the chance encounter on the cliff path triggered off a chain of events that finally made us friends and partners in petty villainies.

It was one of those days when Vappa momentarily regained his old self and craved outdoors, and we were strolling down the path that frilled the north cliff, lined with shacks that sold curios and curiously-named food. Outside a cafe, I spotted Bilal, but for a long moment I could not reconcile what I saw. He was standing on his toes, leaning over the railing the café had put up around the dining area. He had one hand cupped in front of a white couple who sported identical pairs of sunglasses, the other repeatedly tapped his stomach to mime hunger. The couple, their skin tanned to the colour of sandpaper, were watching him the way people watch street stuntmen, with a mild scowl that betrayed neither indulgence nor disapproval.

My face stung at the sight of Bilal begging. I had never seen anybody outside television serials beg with such flourish. Nor had I imagined that anyone who attended school on weekdays would beg at weekends. I passed him with my eyes averted to the sea, my ears tuned to its roar. We were walking past a fish stall – catch of the day sat with sleepy eyes on a bed of crushed ice, traded by a man who knew the English name of every fish and spoke with the civility of a trained salesman because his clients were foreign tourists and hence his wares were unimaginably dear – when I heard my name being called. It took me an effort to not hear him, and I walked faster as his voice grew louder.

‘Are you deaf?’ Vappa snapped. ‘Someone is shouting your name.’

I turned around and saw Bilal, his face flushed from running, his breathing uneven.

‘Hello,’ he panted.

I wanted to say hello and goodbye in the same breath and move on, but Vappa was already holding Bilal’s hand and asking him his name and the location of his residence.

‘Behind the town mosque,’ he said, gasping for breath.

‘Behind the town mosque?’ Vappa pulled a face. ‘Behind the mosque there are railway lines.’

‘In the same premises as the mosque,’ Bilal said and, as Vappa was beginning to knit his eyebrows, he added almost inaudibly, ‘I live in the orphanage.’

Vappa forced a smile and, as if to hide his embarrassment, asked tenderly, ‘What brings you to the cliff?’

I expected Bilal to lie, but he smiled sheepishly and said nothing. The white couple Bilal had begged to walked past us, hand in hand, wind in the hair. The man puffed up his cheeks at the sight of Bilal, the lady removed her sunglasses and rolled her eyes comically at him.

‘You got lots of friends around here,’ Vappa said.

The sun had nearly set, and the lights were coming on in the shacks. Vappa reminded Bilal to start his journey back to the town as it would soon be dark. As if the mere thought of darkness frightened him, Bilal rushed off, blending into little groups of people that drifted down the cliff path. All night I wondered if smiles were all that Bilal could coax out of the white couple with his charade of hunger. But the moment I stepped through the school gates the next morning the riddle solved itself.

‘I have a dollar,’ said Bilal. He was standing by the bird cage, feeding love birds. ‘We will spend it at lunch break.’

This is an excerpt from Anees Salim’s The Small-Town Sea.

5 Rabindranath Tagore Poems that Make Him the Master of Our Hearts

Rabindranath Tagore was a poet-philosopher who inspired a whole generation through his writings. Rabindranath Tagore became a literary sensation and went on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913.

To celebrate Tagore’s birthday, we bring here sections of five of his most beloved poems!

On the Hypocrisy of Faith

On the Vulnerability at the Time of Death

On the Soul of Countries and People

On Missing a Dear One

On Longing

Do you, too, have a Rabindranath Tagore poem to share? What are your favourite lines of his? Tell us, we would love to know!