Explore the world of poetic creation with Gulzar as he brings forth his latest masterpiece, Triveni. Just like the meeting point of three rivers reveals hidden secrets, his Triveni poems bring a twist to each couplet, making it a captivating journey. But that’s not all – discover Neha R. Krishna‘s unique attempt to transform Triveni into Japanese Tanka poetry.

Get ready to be spellbound!

***

Triveni

I was rowing in words and meters of poetry when I happened to invent the form of Triveni. It’s a short poem of three lines. The first two lines make a complete thought, like a couplet of a ghazal. But the third line adds an extra dimension, which is hidden or out of sight in the first two lines.

Triveni ends revealing the hidden thought, which changes the perspective or extends the thought of the couplet. The name Triveni refers to the confluence of three distinct streams or rivers at Prayag. The deep green water of Jamuna, meet the golden Ganga, and hidden from view is the mythical Sarswati, flowing quietly beneath.

‘Triveni’ is to reveal ‘Saraswati’, poetically.

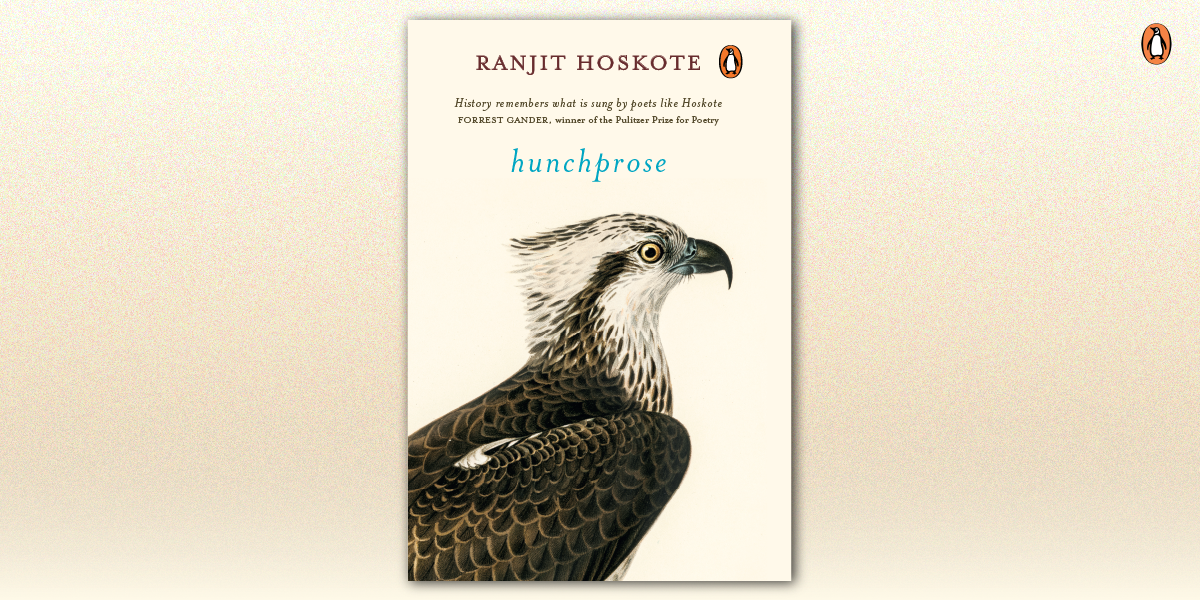

देर तक आस्माँ पे उड़ते रहे

इक परिन्दे के बाल-व-पर सारे

बाज़ अपना शिकार ले के गया !

All the fur and feathers of a bird

Kept flying in the sky for a long time

The falcon swooped away with its prey!

Neha, a young competent poet, was rowing in Triveni. She wished to translate Triveni in a Japanese form of poetry called Tanka. I felt inquisitive. She has explained it in her translator’s note. I hope you too feel as inquisitive while reading it. I found it very interesting.

-Gulzar

***

Translator’s Note

Tanka is a short lyric poem. Various poetic elements like mood, theme, nature, characters, etc., are posed in a particular structure that give Tanka its body and soul. With this concept note, I am addressing the fundamental techniques of writing a Tanka, this will also assist the readers to comprehend and appreciate the structure.

What Is Tanka?

Tanka is a lyrical poem, a short verse, a short song. It is one of the oldest forms, originating in Japan, in the seventh century. A traditional Japanese Tanka has thirty-one morae or sounds that follow a 5-7-5-7-7 sound structure.

The Difference between Traditional Tanka and Contemporary Tanka

Tanka in contemporary English is more flexible and does not adhere to the traditional 5-7-5-7-7 syllabic structure or the pattern of short/long/short/long/long line format.

Why Transcreating Triveni into Tanka?

The aesthetic sense, the grace of cadence and the rich imagery of Tanka appear inclined to Triveni. Even in Triveni, images are juxtaposed with the technique of link and shift. Just like any lyrical Tanka poem, Triveni can also be composed and sung. The length of images of Triveni fits well in Tanka as it gives more space to retain the multi-layered essence. Triveni’s L3 strongly adds to or changes the narration of L1 and L2. In the same way, Tanka has a very strong and unexpected L5.

There is musicality in these short poems even though they never rhyme, which allows them to be enriched with a rustic edge, conjuring up a magical and musical image.

***

उड़ के जाते हुए पंछी ने बस इतना देखा

देर तक हाथ हिलाती रही वह शाख़ फ़िज़ा में

अलविदा कहती थी या पास बुलाती थी उसे?

bird leaves

while the branch sways

in the wind—

urging it to come back

or bidding a goodbye?

***

साँवले साहिल पे गुलमोहर का पेड़

जैसे लैला की माँग में सिन्दूर

धरम बदल गया बेचारी का

a gulmohar tree

at dusk—

as Laila wears vermilion

her religion

allegedly changes

***

सब पे आती है, सब की बारी है

मौत मुनसिफ़ है, कम-ओ-बेश नहीं

ज़िन्दगी सब पे क्यों नही क्यों आती?

to all it comes

everyone has their turn,

death is just

neither less nor more—

why doesn’t life happen to all?

***

काश आये कोई शायर की सुने

शे’र के दर्द से मर जायेगा यह

चाँदनी फाँक रहा था शब भर!

wishing . . . someone

to come listen to the poet

he will die

from the pain of a couplet—

all night was grazing moonlight

***

रात, परेशां सड़को पर इक डोलत साया

खम् से टकर बे ा के गिरा और फ़ौत हुआ

अंधेरे की नाजायज़ औलाद थी कोई!

a wiggly shadow

upset on the street at night

hits a pole, falls and dies—

must be an illicit

offspring of the darkness

***

Get your copy of Triveni by Gulzar wherever books are sold