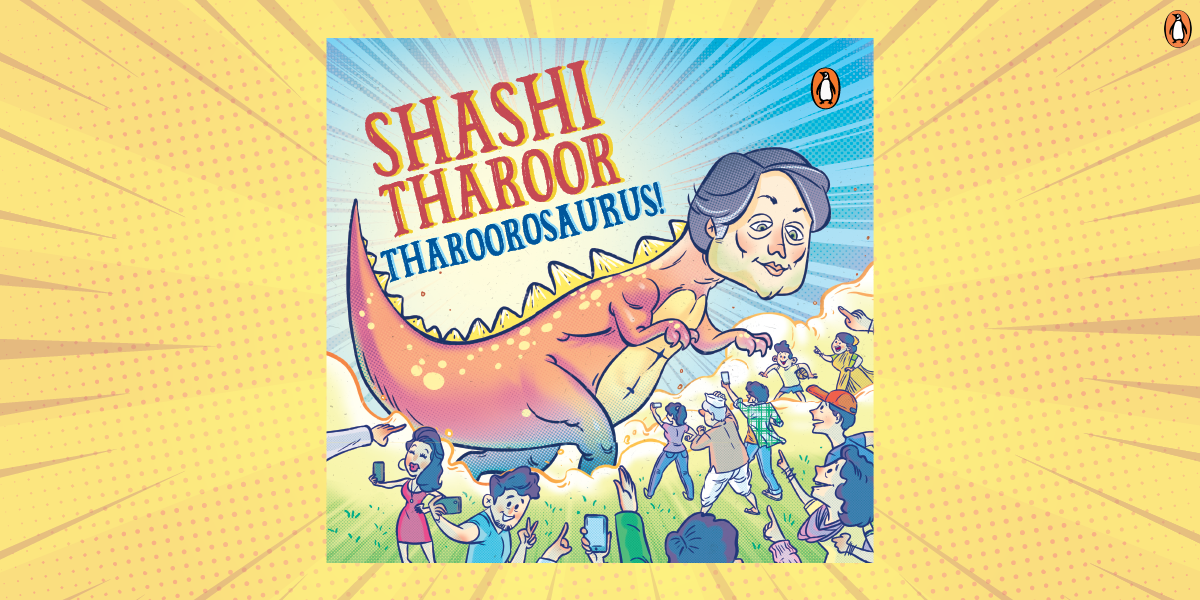

Language can act as a loaded weapon when used with lucidity and eloquence. Shashi Tharoor is the wizard of words, his literary prowess unparalleled. In his book Tharoorosaurus, he shares fifty-three examples from his vocabulary: unusual words from every letter of the alphabet as well as fun facts and interesting anecdotes behind the words.

Today, we are giving you an exclusive glimpse into the exquisite world of Tharoosaurus by sharing five spectacular words from the book with you. Are you ready to impress? Well, here we go!

Agathokakological

Meaning: consisting of both good and evil

Usage: The Mahabharata is unusual among the great epics because its heroes are not perfect idealized figures, but agathokakological human beings with desires and ambitions who are prone to lust, greed and anger and capable of deceit, jealousy and unfairness.

Origin: Coined in the early nineteenth century by sometime British Poet Laureate Robert Southey, best known for his ballad ‘The Inchcape Rock.’

Kerfuffle

Meaning: a disorderly outburst, tumult, row, ruckus or disturbance; a disorder, flurry, or agitation; a fuss

Usage: In view of the kerfuffle around my tweet wrongly attributing to the US a picture of Nehruji in the USSR, I thought it best to tweet some pictures that really showed him in the US.

Origin: Kerfuffle turns out to be quite commonly used in Scots, the language of Scotland, and is an intensive form of the Scots word ‘fuffle,’ meaning ‘to disturb’. The modern word comes from the Scottish ‘curfuffle’ by way of earlier similar expressions that were spelt variously as curfuffle, carfuffle, cafuffle, cafoufle, even gefuffle.

Rodomontade

Meaning: boastful or inflated talk or behaviour

Usage: The politician’s rodomontade speeches sought to conceal his total lack of substance, or indeed of any real accomplishment.

Origin: It originated in the late sixteenth century as a reference to Rodomonte, the Saracen king of Algiers, a character in both the 1495 poem Orlando Innamorato by Count M.M. Boiardo, and its sequel, Ludovico Ariosto’s 1516 Italian romantic epic Orlando Furioso, who was much given to vain boasting.

Snollygoster

Meaning: a shrewd, unprincipled politician

Usage: Though ‘Snollygoster’ is a fanciful coinage in American English slang going back to 1846, it can easily apply to many practitioners of Indian politics in 2020.

Origin: Snollygoster (sometimes spelled, less popularly, snallygaster) was originally, in American English, the name of a monster, half-reptile, half-bird, that preyed on both children and chickens—suggesting rural origins. From its usage in 1846 to describe an unprincipled politician, however, it has come to mean ‘a rotten person who is driven by greed and self-interest’.

Zugzwang

Meaning: in chess and other games, a ‘compulsion to move’ that places the mover at a disadvantage.

Usage: The grandmaster, outwitted by his opponent, found himself in zugzwang and chose to resign.

Origin: Zugzwang, a word of German origin, comes from two German roots, Zug (move) and Zwang (compulsion), so that zugzwang means ‘being forced to make a move’.