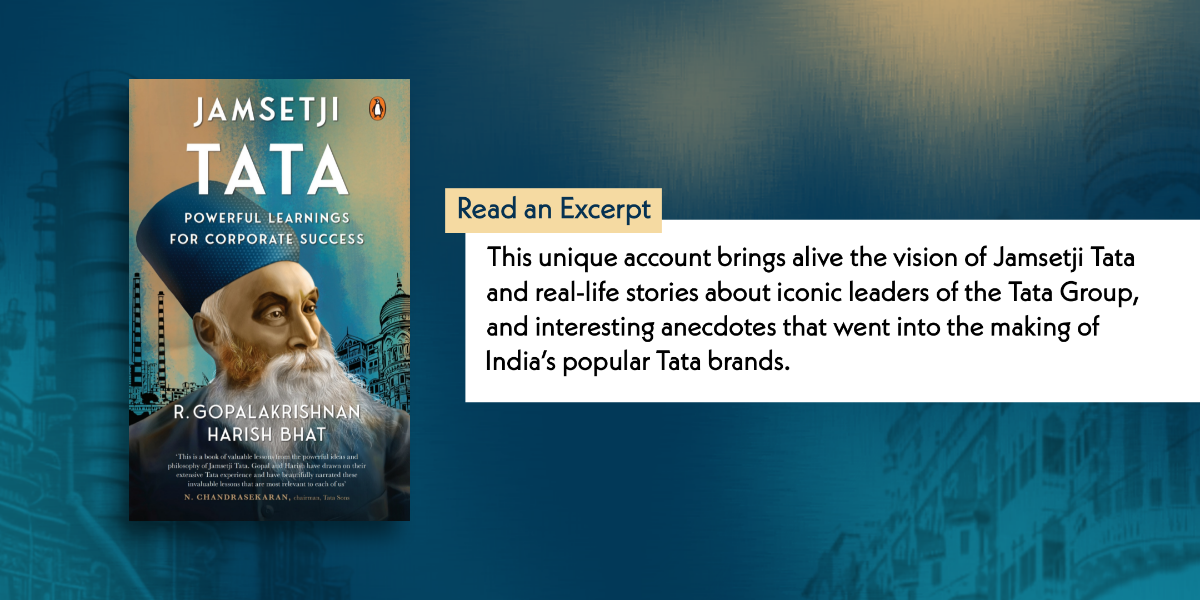

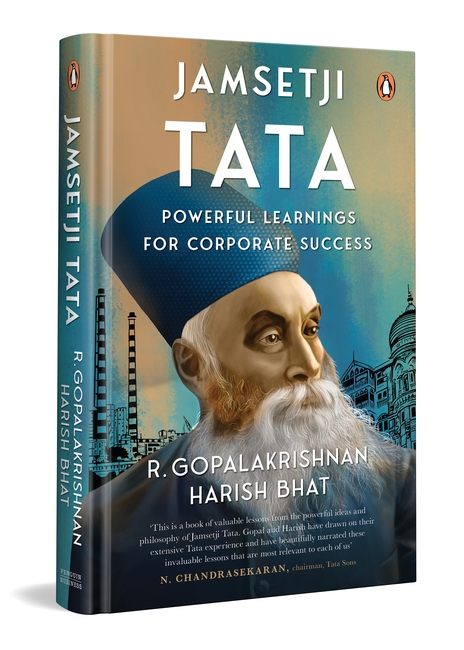

Meet Jamsetji Tata, the icon whose big ideas helped build modern India. In Jamsetji Tata, R. Gopalakrishnan and Harish Bhat reveal how Tata’s vision turned into reality with projects like Tata Steel and the Indian Institute of Science. This compelling account explores how Tata’s relentless pursuit of excellence and self-reliance laid the foundation for India’s industrial prowess, reflecting his legacy continues to drive India’s growth even today.

***

Tata Steel was one of the first great industrial enterprises conceptualized by Jamsetji Tata, founder of the Tata group. Jamsetji believed that steel was essential for the development of a nation. Therefore he was of the view that India should not depend entirely on imports of steel, but should have its own integrated steel plant.

By 1912, Tata Steel had begun production at its plant in Sakchi in eastern India (the town was later renamed Jamshedpur, in honour of Jamsetji Tata). The steel was of excellent quality, thus proving the sceptics wrong. During the First World War, the company supplied over 1,500 miles of steel rails to the Allied war effort in Mesopotamia. Over 8,000 tons of steel shells were made in the openhearth furnaces at Jamshedpur. The plant began running to full capacity on a twenty-four-hour schedule and still could not keep up with the demand, despite producing 150,000 tons of steel annually.

At this point, the leadership of the company—including Dorabji Tata and his partner R.D. Tata—analysed the emerging demand situation and concluded that after the war, India itself could absorb many times this amount of steel. By then Tata Steel was already supplying rails to Indian Railways. In addition, Tata Steel was also earning nice profits on the small consignments that it exported. In December 1916, Dorabji Tata was full of confidence as he spoke to his shareholders about the company’s bumper earnings, production at the plant being 30 per cent over the original capacity and its order book being totally full.

Buoyed by this success, the company began considering a plan of expansion to meet the high current and future demand. Charles Page Perin, who was in charge of this planning, initially recommended to the directors of the company a gradual increase in steel capacity, from 150,000 tons to 225,000 tons a year. He considered this to be a safe and prudent plan.

However, Dorabji Tata had a far more dynamic and ambitious plan in mind. He spoke passionately to the directors about his father Jamsetji Tata’s vision of a selfreliant and strong nation, which was at the heart of his dream for Tata Steel. He recommended a vast expansion programme, which would eventually supply India’s entire requirements of steel. To begin with, this would entail an expansion of the steel-making capacity at Jamshedpur by five times. Dorabji also said he would raise all the required capital from Indian investors.

This ambitious expansion plan, called the ‘TISCO greater extensions programme’, began in right earnest by 1917. However, it ran into a number of difficulties. Tata Steel was compelled to purchase materials at high wartime prices. There were labour strikes in England and a shortage of skilled labour in India. In addition, the Indian rupee depreciated during this time. As a result, the capital cost of the expansion programme, which had been budgeted at Rs 6.8 crore, rose more than three times to Rs 19.6 crore. Additional funds had to be raised from the shareholders because the company’s profits could not support such huge sums of expenditure.

And then, suddenly, after the First World War ended, the company’s profits declined precipitously. This happened because of several factors. Belgium began dumping its steel at very low prices in the Indian market, which had no tariff protection at that time. In addition, Japan, which was Tata Steel’s largest customer of pig iron, was hit by a huge earthquake (the Great Kanto earthquake) in 1923. One of the worst natural disasters ever to strike Japan, the earthquake reduced the country’s financial capability to purchase steel.

By the end of 1923, demand for Tata Steel’s products had fallen significantly and the company’s profits had declined to nearly break-even levels. On the other hand, significant funds had been expended in expanding the plant. This led to a severe cash crunch, and some of the company’s directors even suggested that it go to the British government of India with a request to be taken over by it. R.D. Tata, Dorabji’s partner, rose in angry indignation when he heard this suggestion. He pounded his fists on the table and declared that such a day would never come as long as he lived.

While we do not know what thoughts went through R.D. Tata’s mind when he said this, it is quite likely that he recalled Jamsetji Tata’s objective in establishing Tata Steel—a swadeshi Indian steel company, dedicated to the nation. Instead, what Dorabji and he had in mind was an alternative plan to negotiate with the government to consider imposing reasonable tariffs that would protect Tata Steel from unfair competition from tariff-free European steel.

However, such a plan would take time to materialize, particularly because it involved government policy. In the meanwhile, Tata Steel continued to reel under its immediate miseries, with very little cash in hand to keep operations alive. Dorabji and R.D. Tata struggled to raise funds in the adverse post-war environment. Then, one day, in 1924, a telegram arrived from Jamshedpur at Dorabji Tata’s table, bearing bad news. It simply said that there was not enough

money left to pay wages to the employees of Tata Steel. Would the fledgling company survive, or would it be forced to shut down? Would Jamsetji Tata’s dreams and visions of creating India’s first integrated steel plant come tumbling down? In November 1924, it appeared that Tata Steel was on the verge of closing down.

But Dorabji Tata was a man inspired by the ideals and principles of his father. To him, paying the employees their wages took precedence over everything else because it was livelihoods at stake. He knew that he had to save the company so that it could survive these very difficult times. At that point he took a step that has gone down in the history of the company as the act that saved Tata Steel. His wife and he decided to pledge their entire personal wealth, which came to around Rs 1 crore, to raise funds for Tata Steel. This included all the jewellery owned by his wife, including the famed Jubilee Diamond. This fabulous diamond, weighing 245.35 carats, was twice as large as the legendary Kohinoor and had been gifted by Dorabji to his beloved wife Meherbai many years earlier.

Against Dorabji’s pledge of his personal wealth, the Imperial Bank of India provided the Tatas with a loan of Rs 1 crore. This money was used to pay the wages of the workers at Tata Steel and also to fund the company for the short term. Thanks to this, production of steel at Jamshedpur continued without any significant interruption. The company’s greatest crisis had been averted, and Tata Steel survived.

***

Get your copy of Jamsetji Tata by Harish Bhat and R Gopalakrishnan on Amazon or wherever books are sold.