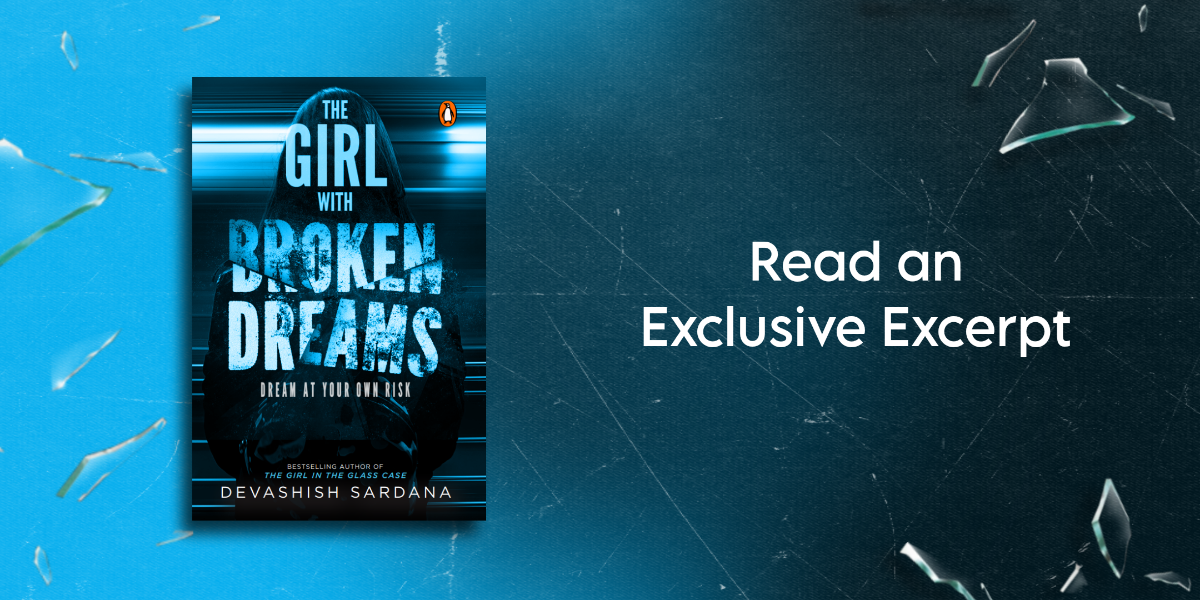

Ever wondered what it’s like to chase down a killer in the blistering Delhi heat while wrestling with your own inner demons? Meet Simone Singh, the fearless CBI investigator from The Girl with Broken Dreams by Devashish Sardana.

As she battles the sweltering sun and mandatory therapy sessions, her journey unfolds in a gripping tale where justice and personal struggles collide.

Read this excerpt to know more, but be sure to grab an icy glass of water or a comforting pillow—you might just need it for the thrilling ride ahead.

***

Assistant Superintendent (ASP) Simone Singh flicks away beads of sweat streaming down her bald, squishy scalp, watching the clock on the Jeep’s dashboard flip over to 10:10. She is now ten minutes late for her appointment with the therapist.

Simone had arrived five minutes before her scheduled appointment, but she has been sitting in the crumbling, Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI)-issued Jeep without air conditioning since. A dry, sultry breeze rushes in through the fully open window, smacking her sweat-speckled face. She detests the summers in Delhi. Even more, she detests the heat crawling up her back and the sweat seeping down her spine.

Simone is parked in front of a plush red-brick bungalow in Delhi’s posh Lutyens Zone. The bungalow stands well back from the pavement behind lush jamun trees. Probably explains the sweetness in the searing breeze.

Her hands grip the steering wheel, knuckles white. Simone is thinking, wondering if she wants to keep her job with the Indian Police Service (IPS). Her boss, Superintendent of Police (SP) Vijesh Jaiswal, had given her a simple choice after the ‘incident’ last month: meet the CBI-appointed therapist or get suspended. Simone would have happily gotten suspended—it wouldn’t be the first time anyway—rather than lie on a sofa and discuss her private affairs with a sham doctor, a stranger. But she knows it isn’t a choice. It is a direct order from a superior. And she isn’t one to break the chain of command. Orders ought to be followed. Period.

She pulls out her phone and flicks through her photos. Simone stops at a photo of her grandma, where she is beaming at the camera, waving a knife, about to blow out the candles on her eightieth birthday.

You see what I have to do because of you, Grams,’ she says aloud. ‘You had one job. One. To stay . . . alive.’ Her voice breaks.

Simone waits, hoping grandma would answer back, calling Simone ‘bachchu’ again in her sing-song voice. Sigh. If only photos could talk.

Let’s get this over with. Simone pockets the phone, puts on an N95 mask, tucks her police cap underneath her arm, and jumps out of the Jeep. She marches to the front gate of the bungalow.

A constable on sentry duty watches her approach, his gaze jammed on her shaved head. Her gleaming baldness has always invited glares. But she is used to the stares and the furtive glances. This is a choice. She had cut her locks two years ago when she had a run-in with the chief minister’s son in Bhopal and was wrongfully suspended. She has shaved her head ever since. Initially, as an act of defiance, now as a proud battle scar.

The constable sees the IPS insignia on her shoulder flash and salutes her immediately. ‘Good morning, madam ji!’

‘What’s the point of wearing a face mask that covers your mouth, but not your nose?’ Simone admonishes the constable, whose face mask has conveniently slipped to his chin. The pandemic might have fizzled out, but good hygiene shouldn’t. And neither should common sense.

The constable flashes a broad grin, his tobacco-stained teeth on full display. ‘Sorry, sorry.’ He hastily pulls up his mask, covering his hideous teeth. ‘How are you, madam ji?’

Simone recoils. She doesn’t have the patience for greetings or small talk. Simone has never understood why people do it. She comes to the point. ‘I have an appointment with Dr Dia Sengupta.’

‘Oh, minister sahab’s daughter?’ Simone narrows her eyes. Granted that the bungalow belongs to one of the cabinet ministers. But how does being the daughter of that minister define a grown, accomplished woman’s identity?

‘No, I’m not here to meet the minister’s daughter. I’m here to meet Dr Dia Sengupta, one of the leading therapists in Delhi,’ Simone corrects him.

The constable scrunches his forehead, confused. ‘Yes, madam ji. They are the same person. Same to same.’ She wants to thump the constable on the head because they are not the same.

But it’ll mean prolonging a conversation that she didn’t want in the first place. Abruptly, she turns away from the constable and strides to the unbolted front gate.

‘Wait, madam ji, you must sign the entry register,’ he calls after her.

Simone stops. Like it or not, she believes that rules must always be followed unless they contradict her values and ethics. She sighs. Turns around. The constable runs to her with an open register and a pen. She scribbles briskly and hands back the register.

The constable squints at what Simone has written. ‘Vijay Singh’s daughter?’ he reads aloud and looks up, confused. ‘Who is Vijay Singh? Your father?’

‘Yes.’

He chuckles. ‘Madam ji, you had to write your name, not your father’s name.’

Simone nods in agreement. ‘As you said, they are the same person. Same to same, right?’ Simone swivels on her feet and marches to the front gate without another word.

***

Get your copy of The Girl with Broken Dreams by Devashish Sardana wherever books are sold.