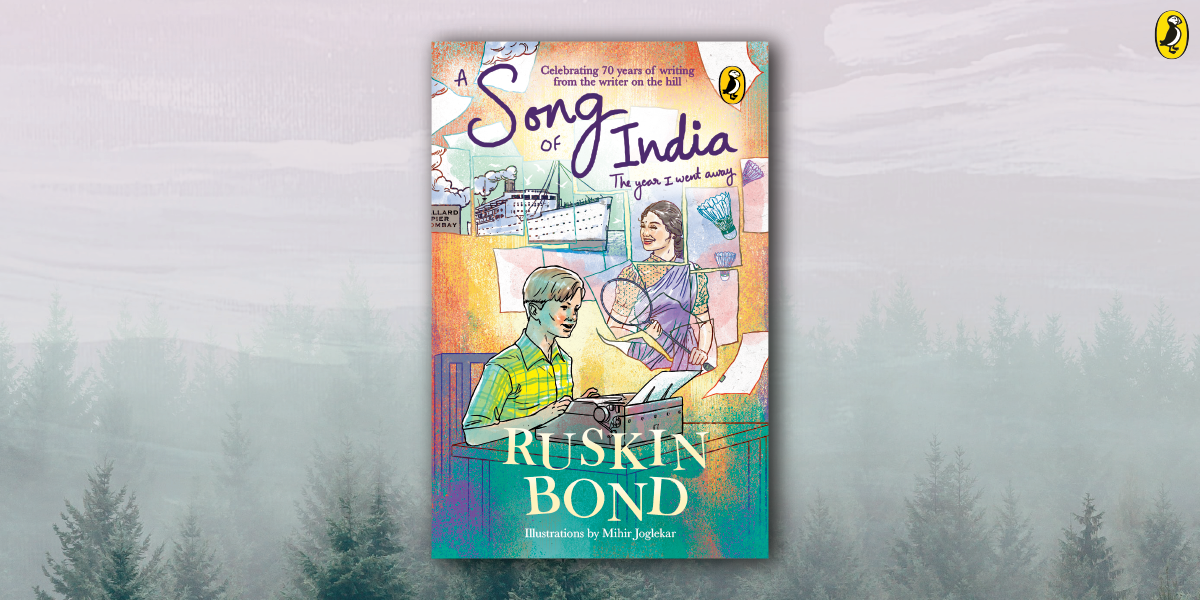

Sixteen-year-old Ruskin, after having finally finished his school, is living with his stepfather and mother at the Old Station Canteen in Dehradun and planning to leave for England to embark upon his writing journey. But the prospect of saying goodbye to the warm, sunny shores of India looms large.

Following the trail of Looking for the Rainbow, Till the Clouds Roll By and Coming Round the Mountain, A Song of India is the story of Ruskin Bond’s last year in Dehra, the year that later became the basis for his first novel, The Room on the Roof. It’s about love, friendship, dreaming, hoping and just being sixteen. Read on for nostalgic look at being young and in the throes of first love in 1950s India.

—

Raj was a couple of years older than me, studying for her BA exams. She wasn’t pretty, but she had a lively, expressive face and an athletic build. She was also her college’s badminton champion. Every evening, she practised on the court she had laid out in front of their house. There was just enough room for it, as a tall hedge separated their place from the rest of the compound. Sometimes I’d watched her playing with her friends. She moved about the court like a gazelle; and she had long arms, which enabled her to reach the shuttlecock from difficult angles. Barefooted, she darted backwards and forwards without seeming to tire. ‘Do you play badminton?’ she asked me after lunch that day. ‘Not after eating half a dozen puris,’ I said from the comfort of an easy chair in the veranda. ‘I’ve only played once or twice.’ ‘Come in the evening and play with me,’ she said.

So that evening, I borrowed Ranbir’s racket and spent an exhausting hour chasing a shuttlecock all over the badminton court. Raj had me on the run from the start of the proceedings, and there was no let up. The score? I think it was 20–0, 20–1 or something like that, in her favour of course. I spent a lot of time picking up the shuttlecock and politely handing it back to her. She offered me a return match the next day, and I was foolish enough to accept. Another love game! And the same the day after. Was I a glutton for punishment, or was I falling in love?

Not head over heels in love, but something more gradual—the pleasure of being in her presence, of the occasional contact, of the sparkle in her eyes. It was a friendship with a girl, and for Raj it was just that—a friendship—while for me, it was something a little more intense. One day, quite by chance, a small sewing needle lodged itself in her heel when she was running barefoot down the veranda steps. I did my best to extract it, taking her foot in my hands and using a pair of tweezers. But I was no doctor, and the needle had made its way further into her foot. We left it alone, assuming it would work its way out. But it appeared to be travelling further up her leg. I had heard of people who had suddenly fallen dead through having needles embedded in various vital organs. Muscular contractions could send an accidentally stuck needle further up her body, working its way between the muscles for considerable distances, until it reached the heart . . .

When I mentioned this to Raj’s parents, they immediately took her to Civil Hospital and showed her to a surgeon. With the help of an X-ray, he located the needle (now in the region of her calf muscle), removed it surgically and sent her home with her foot in a bandage. No badminton for a week. Respite for me from all those love games. But true love it was, for every day I would find myself on a chair beside her, attempting to entertain her with my bedside chatter. I was much better at conversation than at badminton. And after some time, the conversations became quite personal. Raj told me that she wasn’t interested in marriage—she longed for a career in badminton or athletics—but that her parents were already on the lookout for a suitable young man for her. After all, she was nineteen going on twenty.

‘Too young to get married,’ I said, from my seventeen years of acquired wisdom. (I had completed seventeen that summer.) ‘Wait till you’re twenty-five. By then I’ll be twenty-two, rich and famous, and you can marry me and I’ll be your badminton and long-distance running coach!’

—

A heartwarming addition to Ruskin Bond’s boyhood memoirs, A Song of India is a delightful celebration of the beginning of the country’s most loved writing journeys!