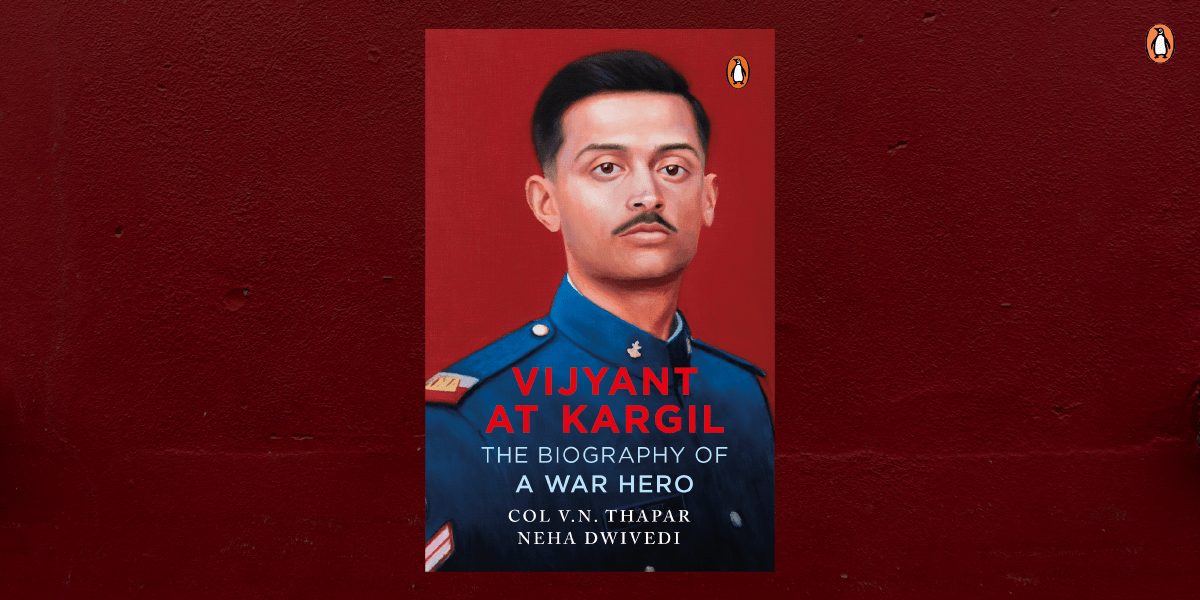

Captain Vijyant Thapar was twenty-two when he was martyred in the Kargil War, having fought bravely in the crucial battles of Tololing and Knoll. A fourth-generation army officer, Vijyant dreamt of serving his country even as a young boy. In this first-ever biography, titled Vijyant at Kargil, we learn about his journey to join the Indian Military Academy and the experiences that shaped him into a fine officer.

Told by his father, Col. V.N. Thapar and Neha Dwivedi, a martyr’s daughter herself, the anecdotes from his family and close friends come alive, and we have a chance to know the exceptional young man that Vijyant was. His inspiring story provides a rare glimpse into the heart of a brave soldier. His legacy stays alive through these fond memories and his service to the country.

Here is an excerpt from the prologue of the book that talks about his last few moments, and the reaction of his friends and family as they received the news of his martyr.

28 June 1999

Finally, the time had come. Men with faces covered with camouflage paint, with the white of their eyeballs visible in the dark, started moving forward silently like ghosts, clutching their AKs tightly. Muscles taut, jaws clenched, they advanced towards the crest. Robin raised his right arm and everyone froze as a shell burst in the sky some distance away, followed by a rattle of fire from the hill about 800 metres ahead. It was still dark but soon the almost full moon would rise and light up the entire area.

He looked at his sturdy G-Shock watch, which read 1945 hours, 28 June. In a few minutes, they would reach their destination. Around fifteen minutes ago, at 1930 hours, heavy artillery fire had started. He did not want to wait a minute longer than required, now that he was so close to the enemy. Suddenly, the machine guns opened up behind him. It was time. They held their breath in anticipation for the signal to move, their eyes fixed on the silhouette of the hill in front, from where flashes of fire were visible. And then it happened. A shell from the enemy guns landed in their midst.

29 June 1999

All of India was in the middle of Operation Vijay. The Indian Army was fighting almost impossible battles on the extremely tough and unforgiving heights of Drass and Kargil. After weeks of bloody struggle, the tables had turned. News of spectacular victories and stories of unbelievable courage of the valiant men in uniform were flooding the news channels, newspapers and magazines. While some just read the news with their morning cup of tea, others extended support to the officers and jawans by way of inspirational letters, cards and other gestures. This was the first time the country was privy to inside news from the war zone, thanks to the various reporters, who brought it right into their living rooms.

On this day, the country was waking up to the glorious news of another important feature, namely Knoll, being captured, ever so bravely, by the officers and men of the ‘Ever-Victorious’ 2 Rajputana Rifles, one of the most prestigious units of the Indian Army. But some families were destined to face the flip side of the victory. The painful side of war.

They woke up to the much-awaited call from the front. However, this time, they didn’t hear the voice they longed for.

A brother had no strength left to hold the receiver of the phone after hearing about his only sibling’s brave sacrifice.

A mother had her heart torn out as she was summoned home in the middle of her working day.

A father, who was always planning and building the brightest future for his son, bit by bit, had his dreams shattered into more pieces than he could count.

A young girl, who was busy counting the days until she would meet the handsome young officer her heart belonged to, was left abandoned.

A little child, who had perhaps learnt to smile again because of her angel in uniform, would never see his face again.

A friend, who was oceans away, had just dreamt of his best friend and woken up with a start, oblivious to what the phone call that would come barely a few minutes later had in store.

To the world he was but a man, but to many others he was the world.

The ‘world’, however, did come together, as the people of Noida made their way to Col Virender Thapar’s house on a hot Tuesday afternoon when they learnt of the brave sacrifice of a son of their own. The young boy—who had run on the streets and exercised in the parks till a couple of years ago, who had donned the smart uniform for barely six months after years of preparation—had breathed his last in the highest tradition of the Indian Army. They couldn’t wait to get a glimpse of the courageous son of their soil. The reaction the sacrifice of this young and valiant officer drew from an entire city was the first of its kind. Until that day, no other event had united the people of the city in such a manner. Men, women and children alike, with an overwhelming feeling of love and respect, came together in large numbers to pay respect to the fallen hero and extend their heartfelt support to the bereaved family. The brave soldier deserved the utmost respect from his country, and every person present was determined to give him just that.

Thousands of people surrounded his house and waited for him to arrive, wrapped in the tricolour. His family and friends tried to hold their own. Their eyes were wet and their hearts heavy despite being full of pride. No one said it aloud, but each one of them silently wished: ‘I wish it isn’t our Robin. Not our sweet Robin.’

Get to know the exceptional young man, and brave soldier, Captain Vijyant Thapar by reading his biography, Vijyant at Kargil. Order the e-book here.