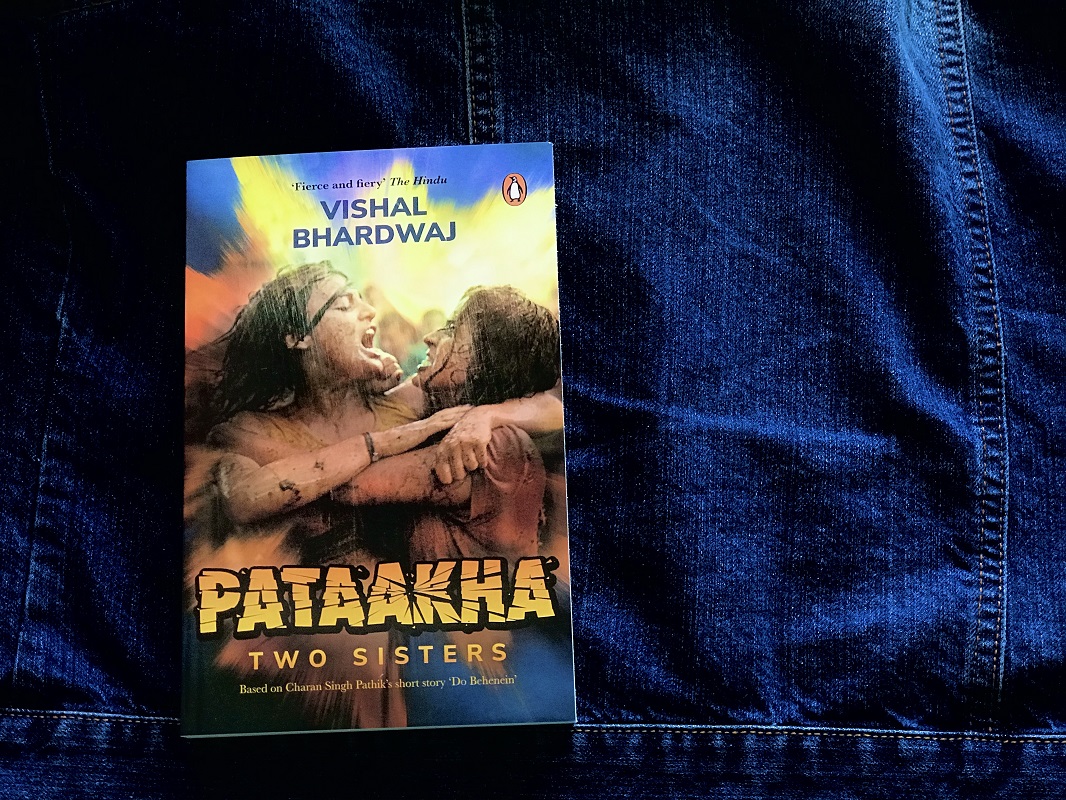

They cannot live with each other, they cannot live without each other. As children, they squabbled all day long. When they were old enough, they married two brothers, and took with them their feuds to their in-laws. Boisterous and fiery pataakhas, sisters Badki and Chhutki are the bane of each other’s existence.

Based on Charan Singh Pathik’s eponymous short story, Vishal Bhardwaj’s adaptation is a hilarious tour de force that obliquely and mischievously takes into its ambit notions of patriarchy and diplomacy between nations. This translation, which includes the novella and the screenplay that the film-maker developed from the short story, not only brings to the reader a rustic, elemental tale rooted in the soil, but also provides a unique glimpse into the art of adapting a literary work into film.

Here’s an excerpt from the book below:

Badki’s husband dropped her back to the village after buying her medicines. Although Badki religiously took her medicines as prescribed, she found no relief even after the stipulated three days. Badki’s husband brought her back to the city. This time he showed her to a specialist who ran a battery of tests.

‘I can’t find anything wrong with these results,’ said the mystified specialist. ‘Let me prescribe some other medicines, however. Come back to me after five days.’

Badki flounced out of the doctor’s cabin in a huff and her embarrassed husband ran after her. She turned on him furiously. ‘What kind of a quack is this guy? He knows nothing. How in the name of the devil will he treat me?’ And with that she returned home, deeply annoyed.

At night, she said to her elder son, ‘Call your cousins in Agra. I want to talk to your maasi.’

The soldier, who had just come home from work, answered, ‘Hello, who is this?’

‘It’s me . . . Golu.’

‘Yes, Golu. Tell me . . . is everything okay?’

‘Everything is fine.’

‘Is budhi-maa okay?’ he said, referring to his mother; all the kids were used to calling their grandmother budhi-maa or ‘old-mother’.

‘Yes, she is. Please give the phone to maasi. Ammi wants to talk to her.’

The soldier handed the phone to Chhutki. ‘A call from home.’

Chhutki snatched the phone. ‘I’m Chhutki. Who is this?’

‘It’s me . . . Badki.’

‘Idiot! Why this urgent need to talk to me?’

‘Did you see the Red Fort and the Taj Mahal?’

‘May you suffer, dari.’

‘I’m already very unwell.’

‘You’ll die suffocating,’ Chhutki retorted, unsympathetically.

‘Did you sit in the aeroplane?’

‘Don’t you dare talk, witch! I’m also unwell. Agra’s water doesn’t suit me.’

‘You left me behind to go gallivanting with your husband. You had to pay, so pay!’

‘You’re a monster from another life, dari!’

‘And acting like a lioness just because you are at a safe distance, you hedgehog! If you have any guts, and are a red-blooded man’s daughter, I dare you to come to the village and face me . . .’ Badki challenged again. ‘Trying to behave like a soldier’s wife from far away!’

‘I’ll be back in two days, dari . . . and then see if I don’t grab your braids, twirl you around and hurl you a hundred yards out! Then you’ll know whether I’m the daughter of a red-blooded man or not!’

The soldier was dumbstruck to see the transformation in his wife. She seemed to have instantly thrown off the wan, sickly air that she had been carrying for days now.

Upon hearing that Chhutki was due to return in two days, Badki immediately switched off her phone.

That night she devoured several rotis and polished off a double helping of milk and rabdi. The next day she tossed out the packet of medicines. She announced, ‘It has been ages since I slept as well as I did last night.’

Will things go too far between Badki and Chhutki? You’ll have to read Pataakha to find out!