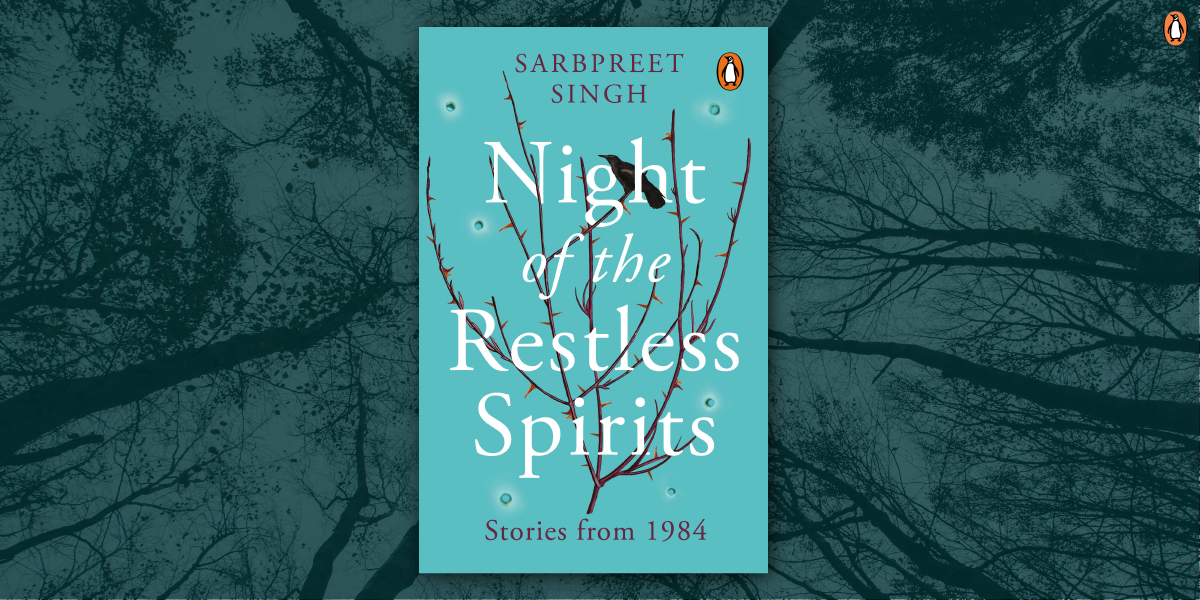

Night of the Restless Spirits is a collection of heart-rending short stories that attempt to capture the 1984 massacre in all its complexity and contradictions. Sarbpreet Singh’s stories take the reader on a journey fraught with love and tinged with tragedy, frayed relationships, the breaking down of humanity and resilience in the face of absolute despair, blurring the lines between the personal and political.

In this insightful account below, author Sarbpreet Singh shares how the 1984 massacre impacted his life and how this collection of stories came to be.

In the fall of 1987, I left India for the US. As a young Sikh who had grown up in Sikkim — a state which borders Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan and Bengal, my connection with all things Sikh was tenuous at best. When the story of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination broke, I was in my final year at the Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS), in Pilani, Rajasthan, which was only a few hours away from Delhi but was far removed from the horrific events that unfolded there. We did have a few moments of alarm. The campus was invaded by ruffians under the command of local Congress leaders; Sikh students mostly went into hiding in their friends’ rooms for a day or so, as did I. There were a few violent incidents which were soon forgotten.

News of the ‘riot’ in Delhi did trickle through, but I don’t remember being particularly upset. I did look like a Sikh and was one, nominally, but to my everlasting shame, I didn’t think of the poor residents of the shantytowns of Delhi who had been butchered as ‘my’ people, particularly. Besides, like most non-Sikhs in the country and many, many Sikhs, particularly outside of The Punjab, I had a sneaking suspicion that we had ‘asked for it’. In those days, before the Internet, the press in India was tightly controlled; sometimes overtly and often voluntarily in slavish allegiance to the ‘National Interest’; every Sikh in India therefore, had the country’s collective finger pointed at him. The cycle of violence in The Punjab, which was fueled much more by cynical political agendas of every stripe, rather than a centralized Sikh insurgent movement, labelled each and every Sikh a villain and a terrorist. I know this because I experienced this first hand and carried the burden around for several years after I left Pilani and went to work in Bombay and Pune. The shouted insults. The suspicious looks. The muttered epithets. The incessant headlines that screamed out the collective guilt of the Sikhs relentlessly. Small wonder then that as a Sikh, I was bereft of self-esteem as well as compassion for the victims of 1984.

The pogrom was squarely cast as a spontaneous outburst in response to Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination and in classic Goebbelsian fashion it quickly metamorphosed into a ‘riot’. The focus rapidly shifted from the murdered, the orphaned and the violated, to the ‘evil’ Sikhs who openly rejoiced at the brutal killing of the nation’s leader. Any twinges of conscience or compassion that might have existed were supplanted by righteous indignation. The propaganda victory was decisive. Away from the Newspeak of the Indian government, I started discovering little bits and pieces that helped me, for the first time, form my own opinion about what had happened to the Sikhs of Delhi — and, of course, those targeted in scores of cities, town and villages across the country.

Somewhat to my surprise, my university library in New York yielded a treasure house of articles written from an independent perspective, almost completely by non-Sikhs. When I had visited Delhi in December of 1984, I had heard whispers about the ‘The Black Book’ within Sikh circles, which purported to tell the true story of what happened in the wake of Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination. ‘The Black Book’ was a booklet titled Who Are The Guilty, a report on the pogrom put together by two Indian civil rights organizations, The People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), led by Mr. Rajni Kothari and The People’s Union for Democratic Rights. In great detail, it documented what had happened in the neighborhoods of Delhi, based on eyewitness accounts. It fearlessly named names. High ranking Congress politicians and ministers; local Congress functionaries; local troublemakers and toughs, who seized upon an unprecedented opportunity to rape and pillage, and ordinary citizens who inexplicably turned against Sikh neighbors, by whose side they had lived amicably for years. The booklet was promptly banned by the Congress government and was unavailable in Delhi. Three years later, in the US, I was able to get my hands on a copy.

Another piece of writing which I discovered was the fearless reporting by Ms. Madhu Kishwar in Manushi. A word about Manushi: it was termed a ‘women’s magazine’ and had a small readership, but in reality was a rare independent and progressive voice in the India of the mid-eighties. Ms. Kishwar’s article detailed the pogrom as starkly and honestly as the PUCL report. The dark mutterings I had heard in Delhi were true! All of it had indeed happened. The capital of the ‘largest democracy in the world’ had indeed turned into a killing field where innocent Sikhs had been butchered with impunity by the very forces that were sworn to keep the peace in the land.

The third piece that had a profound impact on me was a paper by Dr. Veena Das, an anthropologist, published in the journal Dædalus. Based on interviews and field research in some of the poorest and hardest hit neighborhoods of Delhi, Dr. Das told the stories of several children who had been targets of violence during the pogrom. One of the most poignant stories in her paper was about a deaf mute boy called Avtar, whose father had been hanged by a lynching mob during the pogrom. Unable to articulate his pain in any other way, the child could only mime his father’s gruesome end.

The writings of these fearless and principled men and women helped me shed my share of the collective guilt that many young Sikhs of my generation carried around after the events of 1984. It created in my heart empathy for the victims, the children in particular, and tremendous respect for the few courageous ones who stood up for the victims, often at great risk to themselves and their families.

This was the genesis of Night of the Restless Spirits.

—Sarbpreet Singh, author of Night of the Restless Spirits