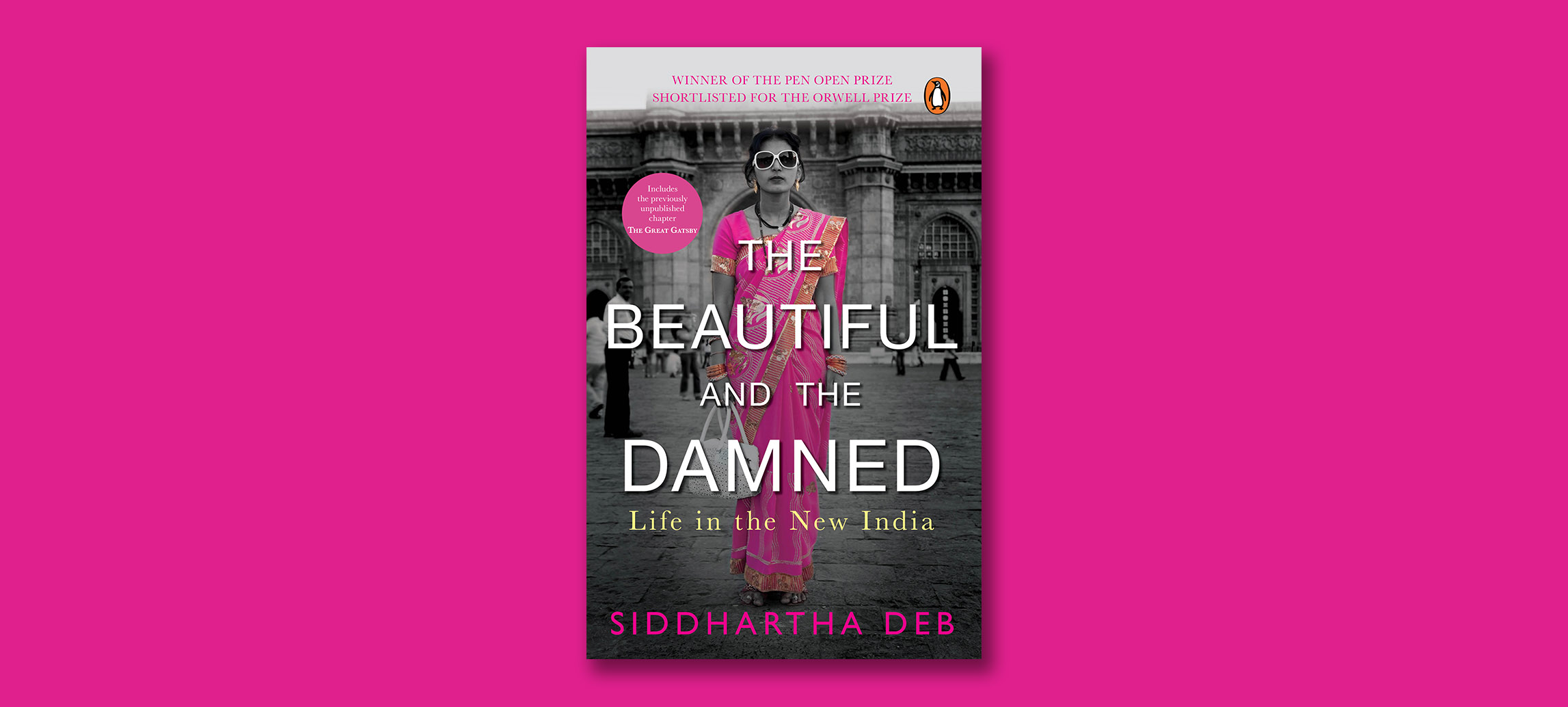

The Beautiful and the Damned examines India’s many contradictions through various individual and extraordinary perspectives. Like no other writer, Siddhartha Deb humanizes the post-globalization experience in the book–its advantages, failures, and absurdities. India is a country where you take a nap and someone has stolen your job, where you buy a BMW but still have to idle for cows crossing your path.

Available for the first time with the controversial and previously unpublished first chapter, The Beautiful and the Damned is as important and incisive today as it was when it was first published. Here is an excerpt from that first chapter of the book, titled The Great Gatsby: A Rich Man in India.

A phenomenally wealthy Indian who excites hostility and suspicion is an unusual creature, a fish that has managed to muddy the waters it swims in. The glow of admiration lighting up the rich and the successful disperses before it reaches him, hinting that things have gone wrong somewhere. It suggests that beneath the sleek coating of luxury, deep under the sheen of power, there is a failure barely sensed by the man who owns that failure along with his expensive accoutrements. This was Arindam Chaudhuri’s situation when I first met him in 2007. He had achieved great wealth and prominence, partly by projecting an image of himself as wealthy and prominent. Yet somewhere along the way he had also created the opposite effect, which – in spite of his best efforts – had given him a reputation as a fraud, scamster and Johnny-come-lately. We’ll come to the question of frauds and scams later, but it is indisputable that Arindam had arrived very quickly. It had taken him just about a decade to build his business empire, but because his rise was so swift and his empire so blurry, it was possible to be quite ignorant of his existence unless one were particularly sensitive to the tremors created by new wealth in India. Indeed, throughout the years of Arindam’s meteoric rise, I had been happily oblivious of him, although once I had heard of him, I began to see him everywhere: in the magazines his media division published, flashing their bright colours and inane headlines at me from little news-stands made out of bricks and plastic sheets; in buildings fronted by dark glass where I imagined earnest young men imbibing the ideas of leadership disseminated by Arindam; and on the tiny screen in front of me on a flight from Delhi to Chicago when the film I had chosen for viewing turned out to have been produced by him. A Bombay gangster film, shot on a low budget, with a cast of unknown, modestly paid actors and actresses: was it an accident that the film was called Mithya? Theword means ‘lies’.

Still, I suppose we choose our own entanglements, and when I look back at the time in Delhi that led up to my acquaintance with Arindam, I realize that my meeting with him was inevitable. It was my task that summer to find a rich man as a subject, about the making and spending of money in India. In Delhi, there existed in plain sight

some evidence of what such making and spending of money amounted to. I could see it in the new road sweeping from the airport through south Delhi, turning and twisting around office complexes, billboards and a granite-and-glass shopping mall on the foothills of the Delhi Ridge that, when completed, would be the largest mall

in Asia. Around this landscape and its promise of Delhi as another Dubai or Singapore, I could see the many not-rich people and aspiring-to-be rich people, masses of them, on foot and on two-wheelers, packed into decrepit buses or squeezed into darting yellow-and-black auto-rickshaws, people quite inconsequential in relation to the world rising around and above them. The beggar children who performed somersaults at traffic lights, the boys displaying

menacing moustaches inked on to their faces, made it easy to tell who the rich were amid this swirling mass. The child acrobats focused their efforts at the Toyota Innova minivans and Mahindra Scorpio SUVs waiting at the crossing, their stunted bodies straining to reach up to the high windows. I felt that such scenes contained all that could be said about the rich in India, and the people I took out to expensive lunches offered me little more than glosses on the above.

A personal, narrative work of journalism and cultural analysis in the same vein as Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family and V. S. Naipaul’s India series, The Beautiful and the Damned is an important and incisive new work.