“One of the great risks of success and fame in the arts is that you could become domesticated or domesticate yourself by wanting to replicate or…reward people’s expectations,” — said the inimitable Arundhati Roy in her lucid voice, enrapturing a packed auditorium as she opened this year’s Penguin Fever, a special edition of the Spring Fever, celebrating 30 years of Penguin in India.

As the autumn chill in the air slowly descended upon an enthusiastic audience queueing up at the gates of the India Habitat Centre in Delhi on October 26, the hall inside warmed up to the lilting voice of Arundhati Roy reading pages from The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.

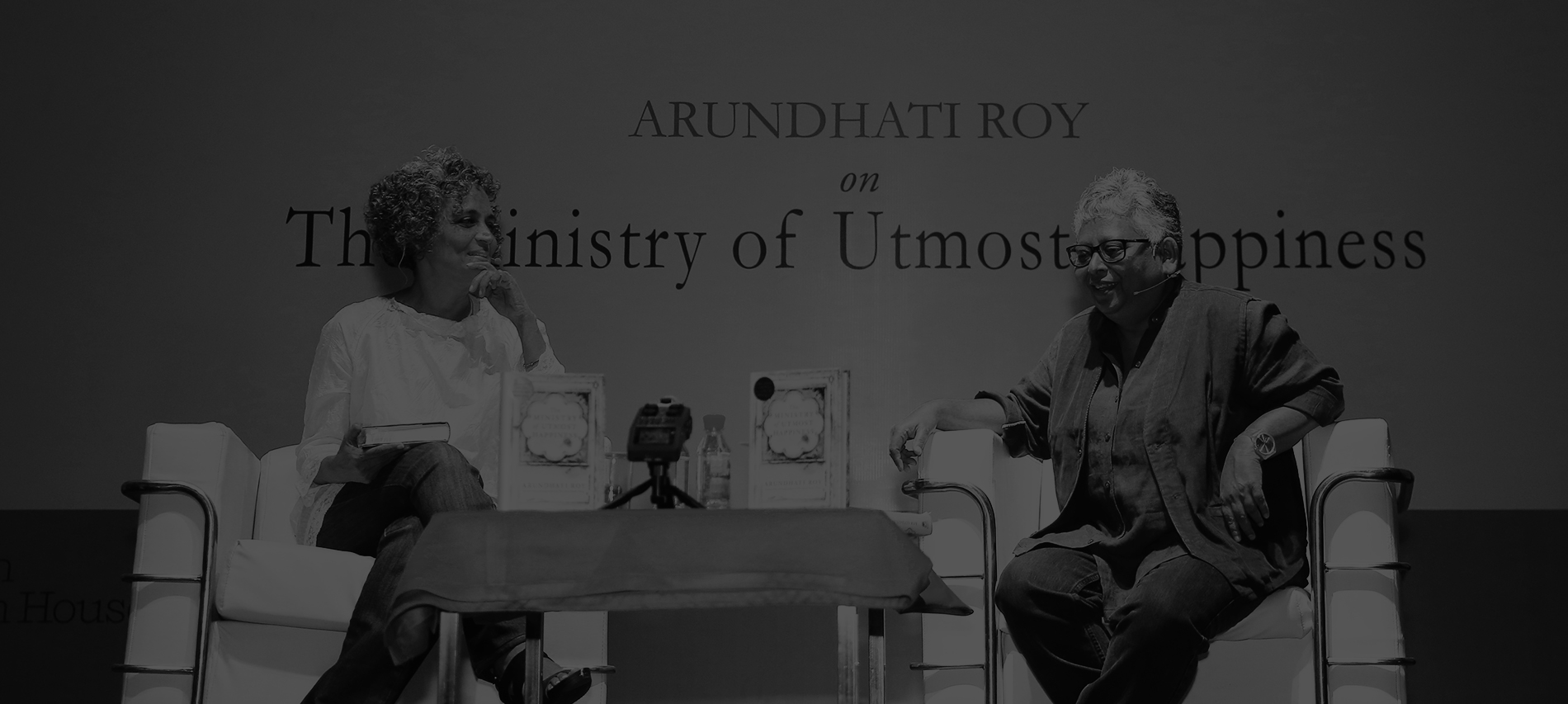

In conversation with professor and documentary filmmaker, Shohini Ghosh, Roy reflected upon her journey through the years as an author and more.

“The God of Small Things blew my life apart, in good and bad ways,” she said, on being asked the question of her 20-year-long sabbatical from fiction writing.

This led Ghosh to ask the writer about the connections between her two works of fiction, especially the curious question — “Where do old birds go to die?” that took off from the pages of The God of Small Things two decades ago and flew all the way into the pages of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Some connections were deliberate, while some others were not, came the reply.

The quaint, haunting world of the Jannat guest house, as built by her character Anjum in the middle of a graveyard, (in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness) houses “social, sexual and political dissidents”, Ghosh remarked. She went on to ask what inspired the writer to sketch these wonderfully unique characters, only to interrupt her own question and ask “Are they around?” to a delighted Arundhati Roy and an amused audience.

“They are here, can’t you see them? They are always around,” quipped Roy as she continued, “They moved in and they are not moving out. They are not going anywhere.”

The author revealed how her early days as a student (and a topper) of architecture had a rather heavy influence on her love for structuring a story. She went on to say, “One of the joys of writing fiction for me, is the joy of being able to describe landscape.” This explains her lavish descriptions of the lands her characters lived in, evoking sparkling images of flowing rivers and animals that can think out loud.

Roy dwelled upon how her stories may have initially seemed to her like cities — concrete, urban jungles, but in reality, they turned out to be “underwater cities”.

On writing, the author said that she does not approve of labels being put on them — “I want to write something that I can’t describe. I want to write something on the air we breathe,” she insisted.

As the floor was opened for the eager, enthralled audience, questions one and many came in from every corner of the auditorium.

To one such query about how she decided to zero down on certain “issues” while writing The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, Roy said she refuses to treat anything as an “issue”.

“It’s a very impersonal thing,” she remarked. To her, “it’s a way of seeing the world,” it’s about the “air we breathe”.

The evening seemed to have passed in the blink of an eye as Roy, on a closing note, left her audience to ponder over a few words — “A novel is a universe I create for a person I love to walk through. I never write for one person.”

As she read a few more lines from her newest book and drew the curtains for the evening, Arundhati Roy’s session set the perfect premise for the festival of words to prepare for the coming five days of Penguin Fever, in the heart of the capital.