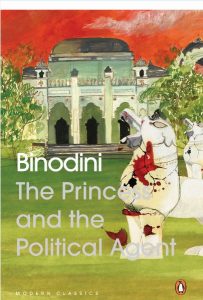

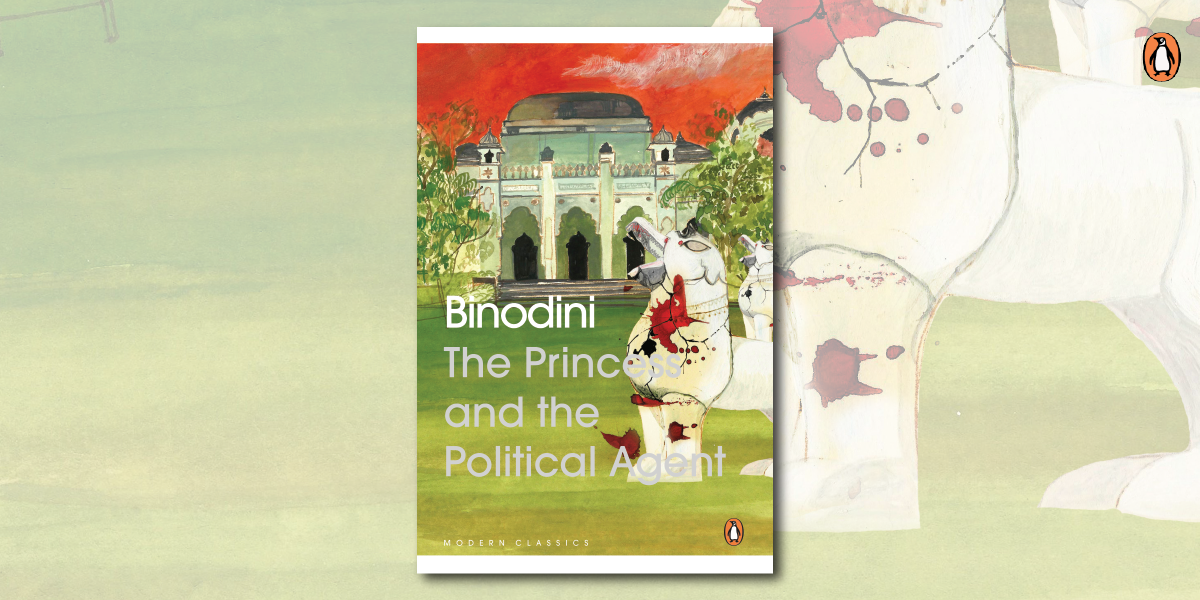

The cover art of Binodini’s “The Princess and the Political Agent” by Shruti Mahajan of Penguin Random House India features, bloody and broken, the leogryphs called the Kangla Sha that stand today in Kangla Fort in Imphal. In the back, a little anachronistically, is painted the palace in Manipur, built for Binodini’s father Maharaja Churachand, himself a major presence in his daughter’s historical novel. It represents the new order in Manipur under the eponymous Political Agent after the Anglo-Manipuri War of 1891. The beasts themselves represent the destruction of the sovereignty of Manipur in the fort where the Princess spent her childhood and youth – and the setting of Binodini’s tales of love, rivalries, and intrigues. Here is the little-known story of these chimerical beasts of Kangla Fort.

Somi Roy, translator.

Today, one hundred and seventy-six years ago, on the 24th of July, 1844, Maharaja Narasingh of Manipur inaugurated the two giant leogryphs that stood guard at Kangla Fort in the heart of Imphal. About fifty years later, they were destroyed by British cannon fire.

Known as the Kangla Sha, the pair of mythical lionesque beasts was made of brick and stood eighteen feet tall. They guarded the entrance to the fort’s inner citadel called the Uttra. The citadel was the innermost enclosure housing the royal residences in the heart of the Kangla, the double moated palace fort of the kings of Manipur. The Meiteis called these guardian beasts Nongsha, literally Heavenly Beasts, retronymically translated as lions which they resembled. They became known as Kangla Sha after the Anglo-Manipuri War of 1891.

The first pair of these leogryphs was constructed by Maharaja Chourjit in 1804. They were Manipuri adaptations of the splendid Burmese mythical beasts called chinthe that guard the entrance of the pagodas of Burma. Ties between Manipur and the glorious and more powerful Burmese kingdoms of Ava, Shan and Mon Burmese – matrimonial alliances, wars, tributes and so on – were well established by the middle of the 18th century. As one of several Manipuri princes who stayed with the Burmese king in the 1760s, Chourjit would have seen the Burmese chinthe in front of their pagodas.

The powerful court of Ava had made remonstrance with the kings of Manipur for profusely gilding and decorating their palaces with royal Burmese emblems and multistage roof buildings. It was looked upon as evidence of the rise of the kings of Manipur. So in 1819 the Burmese invaded Manipur, destroyed the Kangla Fort, and occupied the kingdom for the next seven years.

Kangla Fort was not only the abode of the kings of Manipur but also the symbol of their ancestral roots back to Pakhangba, founder of the Ningthouja dynasty that still exists today. The citadel’s hall was also sometimes referred as the House of Pakhangba, as he was crowned here as the first Meitei king in 33 CE according to the Court Chronicles of Manipur.

For nearly 20 years after Manipur was regained from the Burmese, Kangla remained an abandoned old palace. The monarch after the Burmese expulsion, Maharaja Gambhir Singh, reigned from his capital at Langthabal, eight kilometres from Imphal down the Burma Road. At this time, Manipur was acknowledged as an independent power by the Burmese and the British in the Treaty of Yandabo of 1826. In 1844, Gambhir Singh’s cousin and comrade-at-arms in repelling the Burmese, Regent Narasingh became the king of Manipur and moved the capital back to Kangla. He reconstructed the pair of leogryphs in front of the citadel in Kangla upon the ruins of the old foundation of the previous leogryphs of 1804. The court chronicle of Manipur records that the construction of the two new leogryphs began on June 2, 1844. The Maharaja inaugurated the statues, dedicating them to the royal deity Shri Shri Govindajee on July 24, 1844.

No pictorial representations of the first leogryphs of 1804 exist nor do we know what happened to them after the Burmese destroyed Kangla Fort in 1819. The leogryphs rebuilt in 1844 stood guard at the foot of the citadel, facing west towards the fort’s main entrance, the western gate of the Kangla Fort. They were made of brick, and painted white. They crouched upon their hind legs and stood upright on their forelegs. The tails curled back towards their spines. Their mouths opened wide. The two bifurcated horns, adorning their heads unlike the leogryphs of East and Southeast Asia, were derived from the sangai or the brow-antlered deer (Rucervus eldii eldii) of Manipur. The chimerical beasts bear similarity to the antlered dragon boats of Manipur and to the coat-of-arms of Gambhir Singh engraved above his footprints on the stone he erected at Kohima (now in Nagaland) in commemoration of his victory over the northern tribes in 1833. Therefore, we can surmise that the Manipuri adaptation of the Burmese chinthe was already an addition to the religious and state iconography even before the leogryphs raised by Narasingh.

The leogryphs built in 1844 were destroyed in 1891 after the Anglo-Manipuri War that year. In the events leading up to the outbreak of the war in March, five British representatives had been taken prisoner by the king of Manipur, tried in military court, and executed for their crime for invading the palace of Manipur. The execution of the British men took place in front of these leogryphs and their blood was smeared over the mouths of the two statues. In this, Manipuris saw the fulfillment of an ancient prophecy in Manipur that white men’s heads would fall in front of the beasts. After British retaliation in battle, the Manipuris were defeated and the British occupied Kangla Fort in April 1891.

On June 20, 1891, the Kangla leogryphs were destroyed by cannon fire upon the order of General H. Collett, the commander of the British army, as retribution, symbolic political vengeance, and display of imperial power and dominance.

The British occupied Kangla Fort as a British reserve until their departure in 1947. When young prince Churachand was installed as the new king by the British in 1891, a new palace of Manipur, commonly known as Chonga Bon, was constructed in 1908 about two kilometres away. The fort remained closed to the Manipuri public. Newly independent India succeeded to the Kangla and the fort was occupied by the Indian paramilitary forces. Manipur acceded to the Indian Union in 1949 and in 2004 Kangla Fort was returned to the people of Manipur after a series of public agitations. In 2007 two replicas of Kangla Sha were reconstructed on the original site where they had stood before being destroyed by the British on July 20, 1891.

Wangam Somorjit is the author of The Chronology of Meitei Monarchs (2010), the first edited version of the Court Chronicle of Manipur with corresponding CE dates; and Manipur: The Forgotten Nation of South-East Asia (2016), an anthology of publications from different countries of the region.