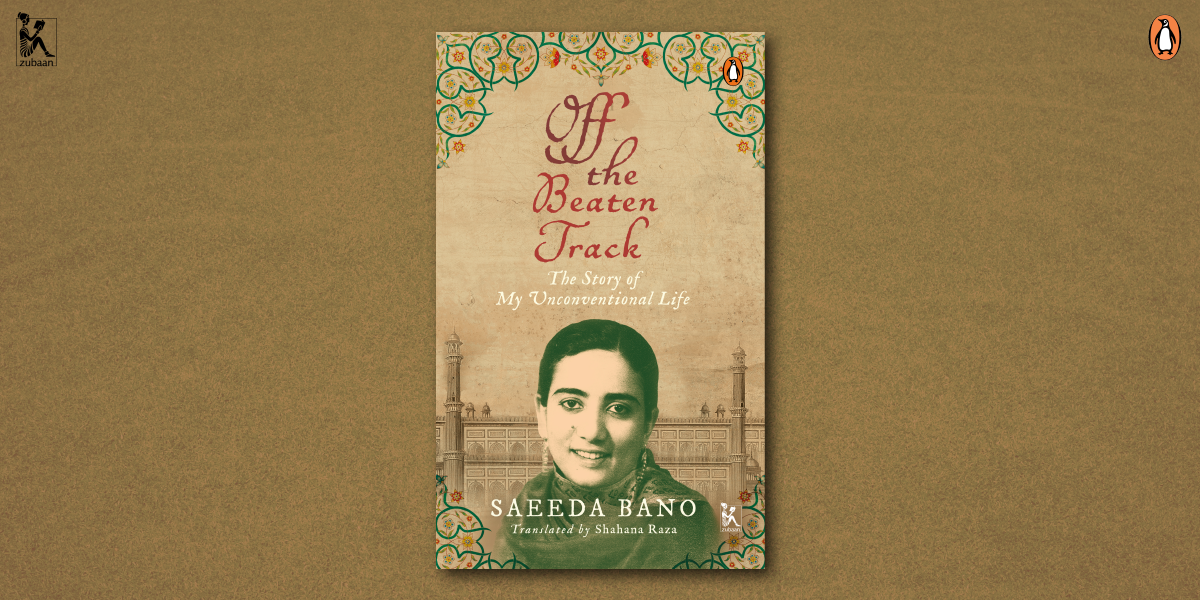

Saeeda Bano was the first woman in India to work as a radio newsreader, known then and still as the doyenne of Urdu broadcasting. Over her unconventional and courageous life, she walked out of a suffocating marriage, witnessed the violence of Partition, lost her son for a night in a refugee camp, ate toast with Nehru and fell in love with a married man who would, in the course of their twenty-five-year relationship, become the Mayor of Delhi. Though she was born into privilege in Bhopal-the only Indian state to be ruled by women for four successive generations-her determination, independence and frankness make this a remarkable memoir and a crucial disruption in India’s understanding of her own past.

**

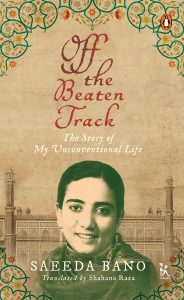

Off the Beaten Track

Saeeda Bano

Why did I think of writing the story of my life? Well, the entire credit goes to my friend Sheila Dhar, whom I met during the most eventful time in the history of our country, back in September 1947. When she saw the unusual situation I was grappling with during those tumultuous days of Partition, it made a deep impact on Sheila’s impressionable mind. She was quite young at the time; I came across to her as an unconventional woman – one who had chosen to take the road less travelled.

As time went by the circumstances I was dealing with became more exceptional. Sheila was witness to all this. She was older now, mature enough to understand what was happening in my life. Perhaps that is why she encouraged me to start writing.

…

Little did I know that one day my circumstances would change so dramatically that by 1947 I would become famous as the first Indian woman to read news for All India Radio’s (AIR) Urdu service. And bless Sheila Dhar, she got me to write this book.

…

On the 13th of August I was to reach office by 6am and read the 8 o’clock bulletin in Urdu. Mrs Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, sister of Independent India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, had been a frequent visitor to Lucknow. She was Beevi’s good friend and because of that I met with her quite often. She treated me like a younger sister. During one such meeting I mentioned I had sent a written application to AIR Delhi for a job. Mrs Pandit was a keen supporter of women’s rights and immediately asked me to give a copy of the application to her. ‘I will try and see what I can do.’ She then sent the letter to a certain Dr Syed Hussain in Delhi with instructions that ‘the work should be done.’ And so it was. How could Syed Hussain not honour Vijayalaxmi Pandit’s orders? That is how I came to Delhi.

I was ready to deliver my very first news bulletin on air on the 13th of August 1947. Prior to this, no woman had been employed by either the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) or AIR Delhi to work as a news broadcaster. I was the first woman AIR considered good enough to read radio news. Of course they had to train me and I was taught how to first introduce myself on air with my name and then start reading the bulletin. The quality of my voice was appreciated. The feedback I got was that listeners were quite impressed by the style in which I delivered the news. The Statesman newspaper even published a few words of praise about me. I believe some people said I must have planted this story. But that’s pure conjecture.

…

I am always grateful to the Almighty that people were eager to hear me read news on radio and appreciated my work. But I never gave this public acceptance undue importance. Hundreds of letters would pour in from various parts of the world in praise of my voice. Several gentlemen even expressed a desire to marry me! Though some of the listeners went as far as to curse me, asking that now that Pakistan had been formed why was a traitor like me still living in the enemy state? From this side of the border, some my own countrymen would write in saying, ‘Get out of our country, go to Pakistan.’

After a while, this continuous barrage of reproach ended, but hordes of letters continued to arrive regularly. I didn’t give them too much weightage nor did they get to my head. I met and mingled with everyone but I did not know how to tell witty jokes or interesting anecdotes, sing or even make delightful gossip at a social gathering.

…

We were in the midst of our discussions when Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru saw us. He came over to where we were and asked, ‘What are all of you doing? Have you had breakfast? You guys have to get here so early in the morning, you must be famished. Come over to Teen Murti House… I will give you brown bread to eat… homemade brown bread.’

Who could refuse the Prime Minister of India? We reached Teen Murti House (former residence of the first Prime Minister of India) and were made to sit in the front veranda on the top floor. Spread out in front of us were the verdant Mughal Gardens and sitting next to us, Nehruji himself. He was busy giving precise orders to the waiter to bring brown bread, cheese and God knows what. Though we were in seventh heaven my mind was preoccupied. I was worried sick and kept wondering where Asad and Saeed could be. Panditji buttered the warmly toasted brown-bread himself, then he sprinkled it lightly with salt added a dash of pepper and asked, ‘Have you ever eaten bread like this?’

‘No I haven’t,’ I replied, thanking him politely as I took the slice.

He then made another toast for me, which I ate as well. But by now I was extremely anxious. Here was the Prime Minister of our country, being hospitable and there I was worried sick with thoughts of where my children could be. Panditji saw the concern on my face and asked, ‘What is the matter? What is bothering you?’

‘My son is lost.’

‘How old is your son?’

‘Eleven.’

‘Eleven year old children do not get lost… he will come. Have your tea, it is getting cold.’

In my heart I so wished Asad and Saeed could have been with me. They would proudly remember this moment, when they ate toasted brown bread prepared by the Prime Minister of India, who made the effort of sprinkling salt and pepper on it himself before handing it around to us. These thoughts were racing through my mind as we finished breakfast. Then we took permission to leave. As we were walking out, Panditji said, ‘An 11-year old cannot get lost. You’ll find him.’

I did a courteous adab and thanked him for his reassurance. As we reached YWCA I saw Asad and Saeed sitting there waiting for me.

**