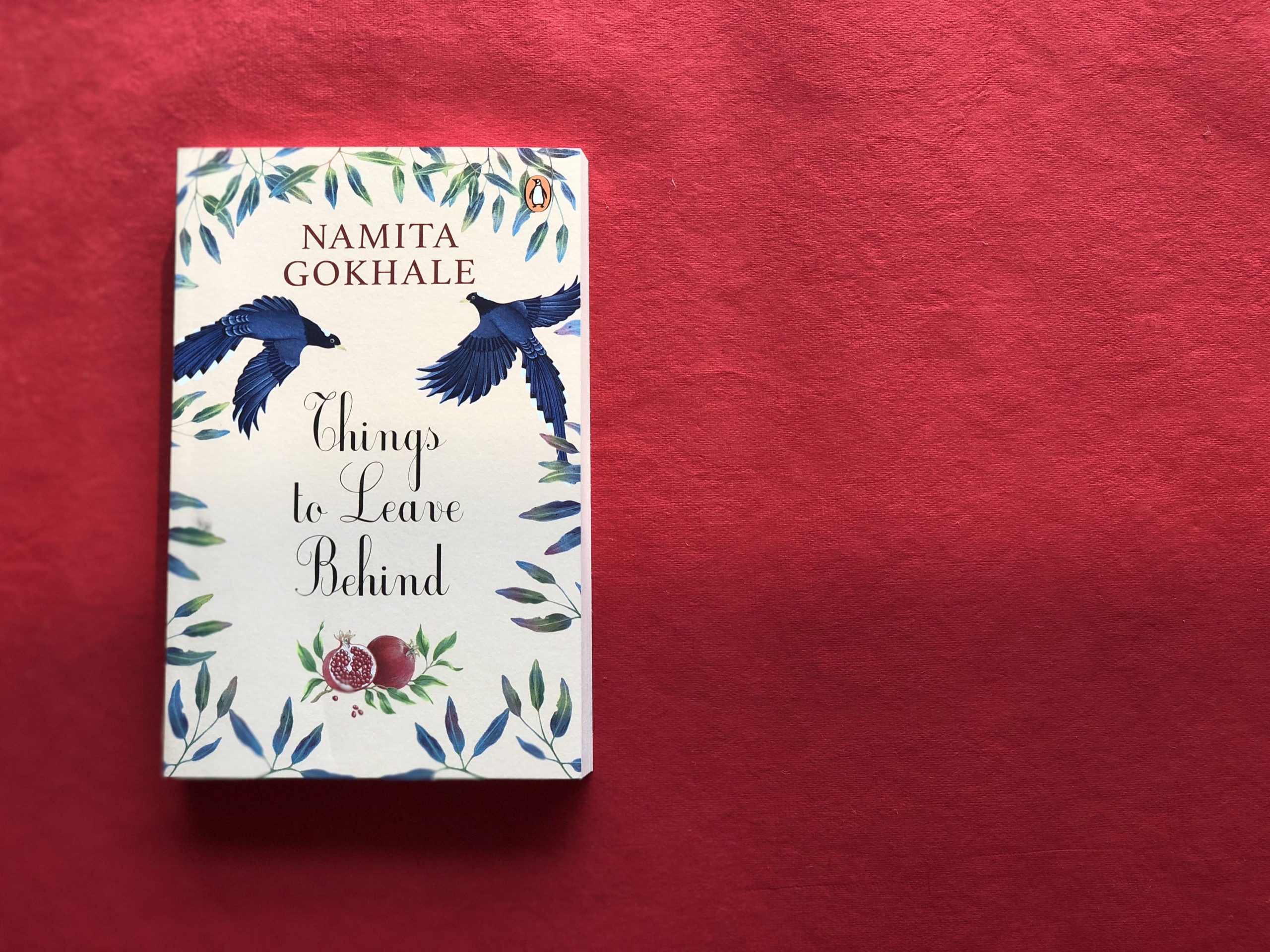

Things to Leave Behind brings alive the romance of the mixed legacy of British-Indian past. A rich, panoramic historical novel that shows you Kumaon and the Raj as you have never seen them, the book is full of the fascinating backstory of Naineetal and its unwilling entry into Indian history, throwing a shining light on the elemental confusion of caste, creed and culture, illuminated with painstaking detail.Things to Leave Behind is a fascinating historical epic and Namita Gokhale’s most ambitious novel yet.

Here is a brief excerpt from the book:

In 1856, just before the fateful year of the Indian Mutiny, a curious phenomenon was observed in the fledgling hill station of Naineetal. Six native women, draped in black and scarlet pichauras, circled the lake for three days, singing mournful songs which no one could understand. As they used the lower road, reserved for dogs and Indians, the British sahib-log chose to ignore their antics.

The Pahari community was, however, thrown into a panic. Thehill people knew, as the British did not, that it was the inauspicious month of the Shraddhas, when the spirits of the dead and gone hover over the lake in the late autumn evenings. Scarlet and black were colours sacred to the death cults and to the goddess Kali. These women could only be dakinis, evil female spirits with some dark, accursed purpose. But they said nothing, not even to each other. They hid their apprehensions behind stern looks and a tight-lipped silence, for, sometimes, to recognize an evil is to give it more force. Then there were the snails.

In the season after the first monsoon showers, snails had begun appearing in multitudes by the lake shore. Now they lay thick on the rocks, layers and layers of them, squirming and undulating. It was not a pretty sight, and Mr Lushington tried his best to investigate the cause of this unusual occurrence. He pored through the first two volumes of the Himalayan Gazetteer, so painstakingly compiled through the admirable efforts of Mr Atkinson. He searched the sections on the forests andwild tribes, and consulted the 1835 treatise on ‘Kemaon Geology & Natural Science’ by McClellant as well as Hooker’s Himalayan Journals: Notes of a Naturalist. Finally‚ he arrived at the conclusion that a particularly prolonged summer had destroyed the frog spawn, and that the mollusc population had consequently proliferated.

The hill folk of course knew better. ‘It’s the voice of the lake goddess,’ they whispered amongst themselves. ‘The lake goddess Naina Devi has sent her servants to announce her displeasure!’ When a young Englishwoman drowned near the rocks by the Ayarpatta shore, a new certainty entered these pronouncements. The whispers were louder and more insistent. ‘The lake goddess demands propitiation,’ the local Paharis told each other. ‘She is avenging the intrusion of the white man on her sacred waters.’

Set in the years 1840 to 1912, Things to Leave Behind chronicles the mixed legacy of the British Indian past and the emergence of a fragile modernity.