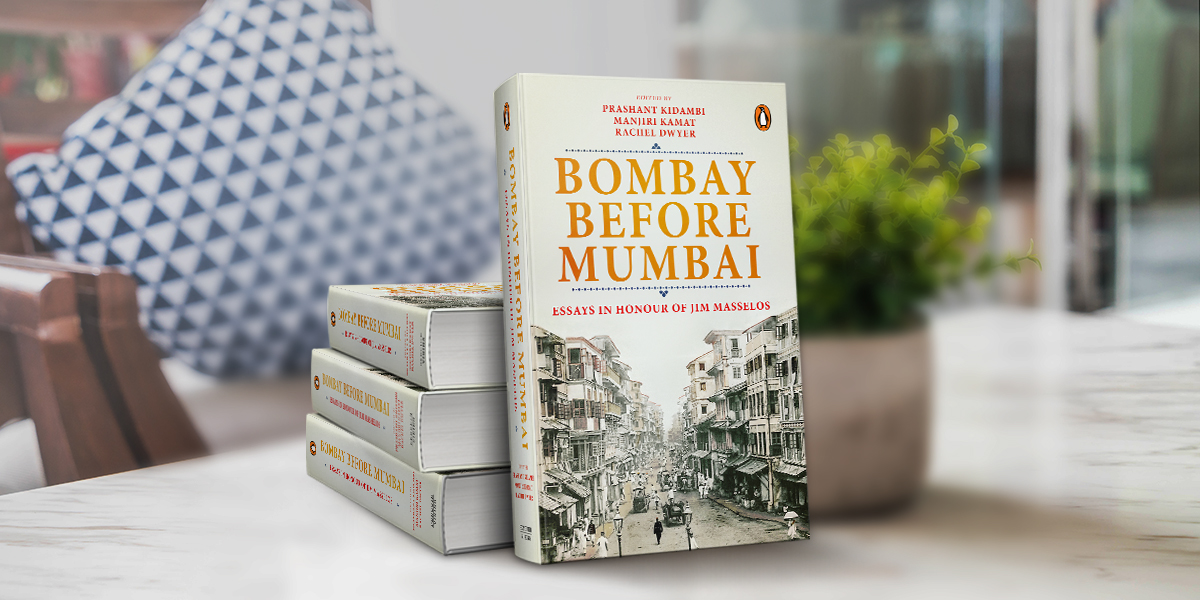

‘City of Gold’, ‘Urbs Prima in Indis’, ‘Maximum City’: no Indian metropolis has captivated the public imagination quite like Mumbai. Bombay Before Mumbai, featuring new essays by its finest historians, presents a rich sample of Bombay’s palimpsestic pasts.

Here’s an excerpt from Preeti Chopra’s essay from the book:

The British colonial regime brought to Bombay the English term and ideal of ‘charity’, complete with religious, institutional and social connotations. Following the literary scholar and novelist Raymond Williams’s untangling of the word, ‘a charity as an institution’ was established in the seventeenth century, replacing the older meaning of the notion as ‘Christian love between man and God, and between men and their neighbours’. From the eighteenth century onwards, the institutionalization of charity resulted in a sense of revulsion to the term itself that came from ‘feelings of wounded self-respect and dignity, which belong, historically, to the interaction of charity and class-feelings, on both sides of the act’. This later led to the ‘specialization of charity to the deserving poor’ (a reward for approved social conduct) and to upholding the bourgeois political economy so that charity did not interfere with the need to toil for wage-labour.

British notions of charity and philanthropy intersected with, and influenced, Indian forms of gift giving. Douglas Haynes has underscored ‘the importance of gift giving in Indian ethical traditions’. Native businessmen in western India actively participated in this arena, which included the construction of wells, rest houses, support of festivals and Sanskrit learning or other arenas that were valued by their community. These were religious acts in the service of deities, through which the devotees hoped to earn merit. But gifting activities were also tied to the world of business. Writing of the merchants of Surat, Haynes emphasises the importance of a abru u (reputation), which required careful nurturing and maintenance, adherence to community norms and support of community religious and social life. A Abru u also denoted ‘economic “credit”’. It was essential for businessmen to establish a reputation of reliability in order to participate in vast commercial networks that were based on trust rather than enforceable legal contracts and modern financial institutions. Gifting was also used to exert political influence over rulers who came from outside the city and distinguished themselves from the culture and norms of the merchants. Here, the gifts made by merchants accorded to the norms of the rulers. According to Haynes, under British rule in the nineteenth century, this form of gift shifted ‘from tribute to philanthropy’, as merchants started to contribute towards secular institutions such as schools, colleges, or hospitals. Gifting for secular philanthropic works of ‘humanitarian service’, Haynes argues, diffused ‘an entirely novel ethic from Victorian England among the commercial communities of India’. Thus, even as merchants continued to uphold their reputations by gifting practices that maintained community religious norms and social life, they adjusted other practices to the norms of the ruling group. Building on and moving beyond Haynes, I underscore in this chapter how native elites also donated to charities that supported the European poor and, occasionally, Christian religious institutions primarily geared towards Europeans.

In the nineteenth century, colonial legal interventions transformed native practices of charitable gifting by making them transparent and bringing them under government control. As Ritu Birla shows, the Charitable Endowments Act of 1890 and the Charitable and Religious Trusts Act of 1920 introduced the criteria of ‘general public utility’ for determining charitable purpose. Yet, religious institutions were excluded from the category of charitable trusts until the Act of 1920 ‘established that religious trusts deemed of public import would also be eligible for classification as charitable trusts, and thus be classified as tax exempt’. An example of a religious trust of public import were dharamshalas, or travellers’ rest houses, which offered free room and board Primarily used by merchants, they were open to religious mendicants and those of ‘pure caste status’. Yet, in most cases, entry was denied to those of lower castes and untouchables.

From the 1890s onwards, as courts increasingly began to consider cases involving the ‘public nature of indigenous endowments … the question of public benefit came to rest less on equal access to all potential beneficiaries and became instead one of serving more than just the family or trustees.’ In the 1890s, the British saw dharamshalas as ‘valid religious but not public charitable trusts’. By 1908, however, they clearly considered them as institutions of public benefit. The 1920 statute allowed the Government of India to give local government and courts greater regulatory controls over public religious and charitable trusts, at the same time as it forced trusts to publicise their finances and accounts.

Thus, to summarise, in colonial India, charity retained a religious basis, serving specific communities, and excluding others. It remained distinguished from philanthropy, which had secular humanitarian goals, and served the public at large. While the institutionalisation of charity in Britain encouraged popular feelings of social revulsion and channeled aid towards the deserving poor, nothing suggests that all Indian communities felt the same way, at least in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Bombay Before Mumbai is a fitting tribute to Masselos’ enduring contribution to South Asian urban history.The book is available now!