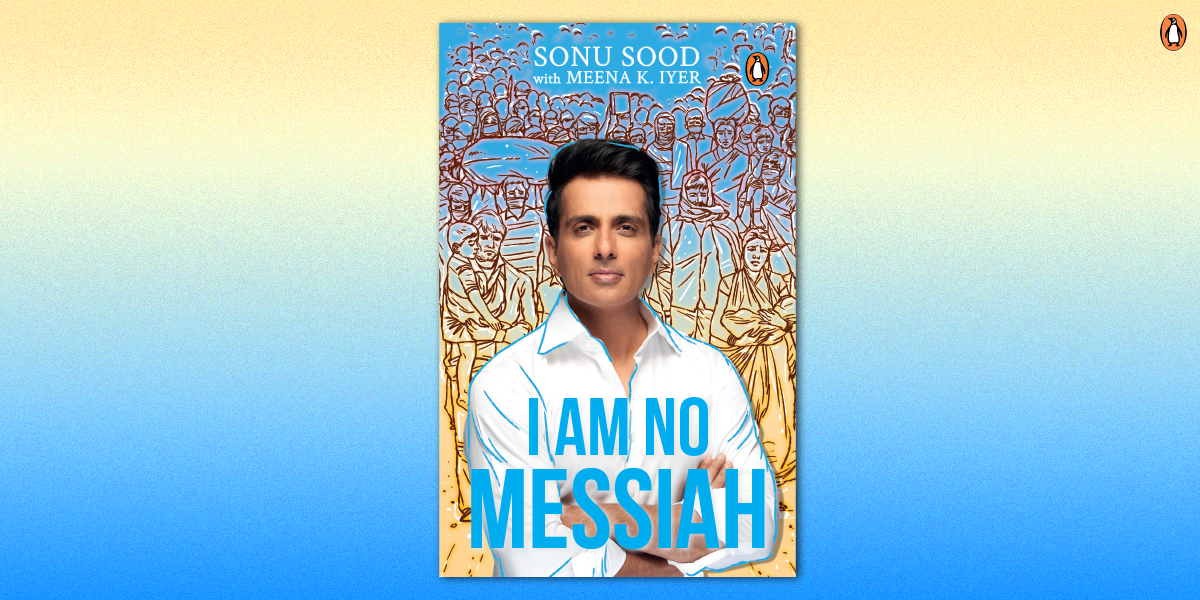

During the nationwide lockdown, imposed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, when a wave of poverty-stricken migrants set out on foot to make their arduous journey back home, the value of seva, service to mankind, instilled in him by his parents, spurred Sonu Sood into action. From taking to the streets and reaching out to the stranded, to setting up a dedicated team and making arrangements for national and international transport, Sonu managed to help thousands of helpless and needy workers.

In his memoir, I Am No Messiah, Sonu Sood combines the extraordinary experiences of his journey from Moga to Mumbai with the writing skills of veteran journalist and author Meena K. Iyer. Honest, inspirational and heart-warming, this is the story of Sonu Sood and of the people whose lives he continues to transform.

In this excerpt from the book, Sonu Sood shares how his life mirrored the events that were shown in Airlift, a Bollywood movie starring Akshay Kumar that he was deeply moved by.

**

A movie in which I had no part to play but which nonetheless affected me deeply was the inspirational Airlift (2016), directed by Raja Krishna Menon. In this film, Akshay Kumar played a Kuwait-based Indian businessman named Ranjit Katyal. I had my heart in my mouth when the protagonist evacuated 1,70,000 Indians from Kuwait after Saddam Hussein attacked the country; and I felt a lump in my throat when Akshay raised the Indian tricolour at the end of a victorious airlift. Patriotic films usually have that effect on me. And for some reason, Airlift, the movie, stayed with me; it had that kind of strong impact on me.

The inexplicable connection I had with this film showed up on 29 May 2020. I felt a sense of déjà vu when, in the midst of the lockdown, I managed to evacuate and airlift a large group of people from one state to another. A total of 177 men and women had to be picked up from Kochi, Kerala, and carried to safety in Bhubaneswar, Odisha. There was so much detailing in the plan and such fine points to be covered in the execution that I felt I was watching Airlift again.

My personal Airlift thriller, as true to life as Akshay’s film, began with a message on my Twitter timeline. I was informed that there were 167 women stranded in Ernakulam close to Kochi, Kerala, who needed to be rescued and sent to Odisha. They worked in an embroidery workshop. There were ten boys too, who were plumbers, electricians and miscellaneous job workers in and around the factory premises.

The factory had closed soon after the lockdown was imposed in Kerala, leaving these Odia workers high and dry. The women had no shelter and hardly any food in Kerala. They also barely knew Malayalam, the state’s language. In short, they were cash-strapped and helpless. But help comes from the most unexpected sources. Someone guided these women to reach out to me, and that’s when I got their message on my Twitter timeline.

It was a massive, mind-numbing operation for my team and me. There was no local transport available to fetch this group of women from the factory premises where they were bunched up. They had but one intense desire: ‘Come what may, we want to go home.’ I learnt that they all hailed from the same district, Kendrapara, in Odisha.

With local transport unavailable and airports all over the country closed, we had to obtain permissions and coordinate at several levels. Once again, an engineer’s blueprint for action had to be drawn.

Accordingly, I first reached out to some authorities at Air Asia. Once they were convinced about the immediacy and the integrity of my request, they agreed to send an aircraft from Bengaluru to Kochi to airlift the girls and take them to Bhubaneswar. In Kerala, we had to arrange for a minimum of seven large buses to fetch the 167 women from Ernakulam and drop them off at the Kochi airport in time to catch the flight. But it was not smooth sailing.

I am No Messiah

Sonu Sood, Meena K. Iyer

When the buses were loaded, there was a crisis. The ten men, the assorted plumbers and other workers who had also been stranded in and around the factory, wanted to join the women and go home. However, the security guards at the factory did not allow them to board the bus. When one of them dialled me and pleaded for help, another round of talks ensued, this time with the security personnel at the factory. They were convinced and permitted the men to board the buses. As in every operation, whether it was by bus, train or plane, I had to be available round the clock to pick up the phone to sort out last-minute glitches and seek eleventh-hour clearances. It wasn’t possible to delegate responsibility and go lock myself up in an air-conditioned bedroom. It was my voice that opened doors; I had to be on call.

I cannot count the number of phone calls that went back and forth to meet the challenge of opening up two airports, Kochi and Bhubaneswar. Until the airport authorities in both cities were convinced that it was an emergency operation, that this group of men and women had to get back home, I had to keep speaking to people. I could breathe only when both airports were opened for this flight to take off and land.

**