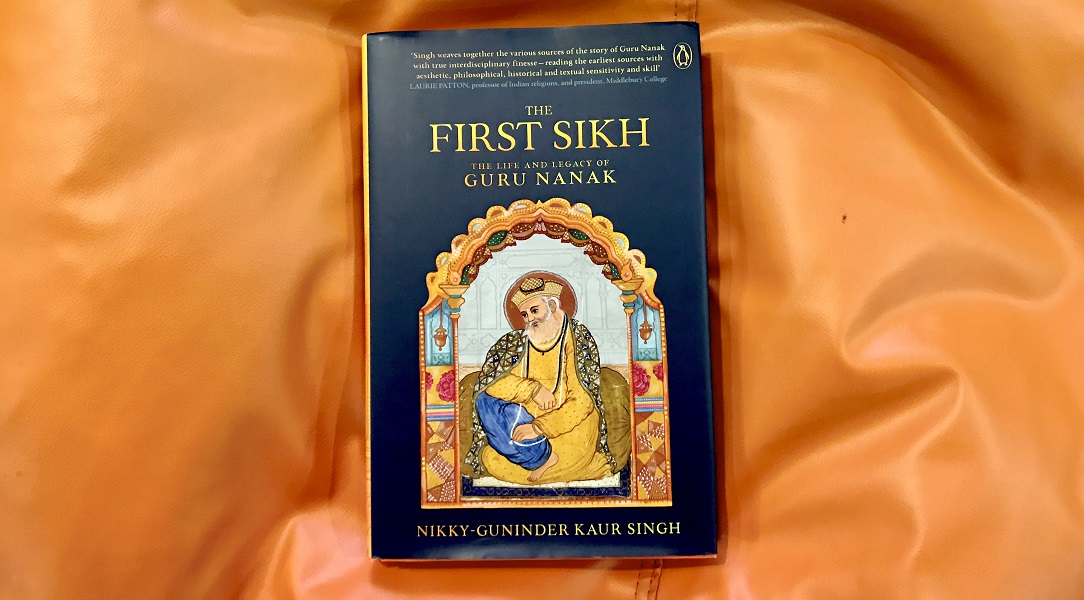

History is telling and re-telling of stories by one generation to the next in the form of illustrations, written texts and verbal narrations. Janamsakhis are the birth (janam) and life stories (sakhis) of First Sikh – Guru Nanak. While the earliest of the existing Janamsakhi – Bala, (dated 1658) is a compilation of 29 illustrations, the B-40 Janamsakhi (dated 1733) is considered to be the most significant for its nuanced and detailed depiction through 56 illustrations.

The narratives in all Janamsakhis are linearly portrayed from birth till death but vary across time, region, and artist. Through detailed study of Janamsakhis, the author of The First Sikh attempts to convey the central meaning of these stories, that is that, “the First Sikh reaching out to people across religions, cultures, professions and societal hegemonies, and embracing them in his profound spirituality”.

Here are the most important lessons that we gain to learn five and a half centuries hence.

*

Greatness lies in our deeds

The portrayal of the First Sikh in the form of an ordinary human being, without a halo, validates his temporal and historical presence in our world. The Janamsakhis present a natural progression of the First Guru as a baby boy to a bearded middle-aged man into a grey bearded old man.

“Rather than any exaggeration of external features and spacing, what spectacularly emerges is the Guru’s inner power and spirituality. In the early illustrations he is not depicted with even a halo. Yet, the First Sikh’s simple pose, whether standing, sitting or lying down, and his gentle gestures addressing people from various strata of society and personal orientation spell out his greatness.”

*

Imbibing a pluralist approach

Various illustrations in Janamsakhis indicate the First Guru’s acceptance of beliefs and practices of different culture, both in his gestures and physical appearance.

“The illustrator of the early B-40 Janamsakhi accomplishes it by utilizing disparate motifs of the tilak and the seli: Guru Nanak almost always has a vertical red tilak mark on his forehead, just as he has a woollen cord, seli, slung across his left shoulder coming down to his right waist.” … “Evidently, the bright red line between the Guru’s dark eyes or the dark semicircle sinuously clinging his yellow robe go beyond art for art’s sake attractiveness: the tilak is saturated with the holiness of the Vaishnava Hindus; the seli with the devotion of the Muslim Sufis.”

“In almost all of his adult images Guru Nanak in the B-40 has in his hand a simple circle of beads on a string, ending in a tassel…” “Thought to have originated in Hindu practice, the ‘rosary’ is a widespread and enduring article used for meditation and prayer by Buddhists, Muslims and Christians alike.”

*

Rejecting divisive cultural and political beliefs

The Janamsakhis elucidate the First Guru’s firm belief in equality and dismantling cultural practices that divide the community on the basis of caste, religion, and profession. A sharp and effective rendition of one those incidents is when young Nanak refuses to “participate in the upanyana ceremony, reserved for upper-caste Brahmin, Kshatriya and Vaishya boys” and questions the priest who proceeds towards him with a sacred thread (janaeu). He retorts,

“‘Such a thread,’ continues Nanak, ‘will neither snap nor soil, neither get burnt nor lost.’ His biography and verse are thus blended together by the Janamsakhi authors to illustrate his rejection of an exclusive rite of passage antithetical to the natural growth of boys from all backgrounds alike. A young Nanak interrupts a smooth ceremony in front of a large gathering in his father’s house so that his contemporaries would envision a different type of ‘thread’, a different ritual, a whole different ideal than the rebirth of upper-caste Hindu boys into the patriarchal world of knowledge. That everyone treat one another equally every day is the subtext.”

*

Living a truthful life

The Janamsakhis vividly and repeatedly portray the quintessential message of taking responsibility of our actions and performing our worldly duties in the society.

“Coming across some Pandits offering waters to the rising sun, the Guru begins to sprinkle palmfuls of water in the westward direction. When asked about his contradictory act, he simply responds that he is watering his fields down the road. This tiny story raises a loaded question: Is taking care of crops and other honest work any less than feeding distant dead ancestors? He draws the attention of his contemporaries to matters of living a collective responsible moral life. Whatever the setting, he conveys the futility of rituals and highlights truthful living midst family and society on a daily basis.”

*

Engaging in community service

After his spiritual transition, when Guru Nanak reappears in river Bein after 3 days of immersion, he travels far and wide with Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana to disseminate the importance of community service.

“As he reincorporates into society, ‘antistructure’ becomes the mode of existence. The earliest Sikh community that developed with Guru Nanak at Kartarpur fits in with the cultural anthropologist Victor Turner’s description of ‘antistructure’ because the neat horizontal divisions and vertical hierarchies of society were broken down.” … “The three important socio-religious institutions of Sikhism: seva (voluntary service), langar (community meal) and sangat (congregation) evolve in which men and women formerly from different castes, classes and religions take equal part.”

*

Nurturing our body and participating in the natural, social and cosmic process

The Janamsakhis depict the extensive dialogue between Guru Nanak and the various ascetics. It comprehensively displays the conflict between Nanak’s belief in accepting and nurturing our body and the Naths’ ideals of “smearing ash on their bodies as a symbol of their renunciation”. Artist Alam presents an incident in B-40 Janamsakhi where,

“We see Guru Nanak climbing up a mountain where a conclave of Nath yogis is sitting (#20 in the B-40). The artist paints them with their backs against the world. Some have smeared. Their shaved heads, lengthened earlobes and long earrings (kan-phat, ‘ear split’) signal their rigorous hatha yoga practices and ascetic ideals.” … “Guru Nanak’s pictures with the various ascetic groups resonate with scriptural verses: rather than ‘smear the bodies with ashes, renounce clothes and go naked—tani bhasam lagai bastar chodhi tani naganu bhaia’ (GGS: 1127), we must ‘wear the outfit of divine honour and never go naked—painana rakhi pati parmesur phir nage nahi thivana’ (GGS: 1019).”

Pick your copy of The First Sikh to learn how the Janamsakhis gather meaningful incidences that are essential for the unity and continuity of the Sikh community.