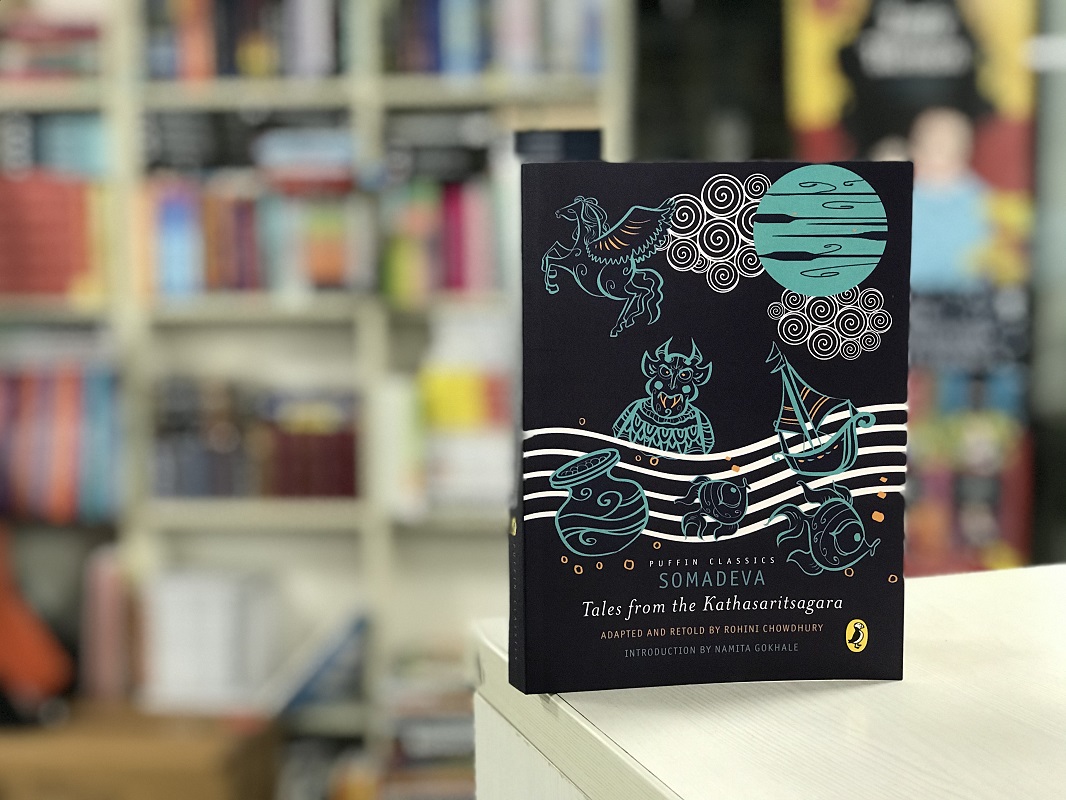

Do you know the story of Phalabhuti, who narrowly escaped a grisly fate?

Or of the kind-hearted Jimutavahana, who was willing to give his life to save a snake from death?

These are just some of the many tales that make up Somadeva’s Tales from the Kathasaritsagara, a classic work of Sanskrit literature that is full of memorable characters. Adapted and wonderfully retold by Rohini Chowdhury, this is a timeless classic that will entertain and enchant readers everywhere.

Not convinced yet? Rohini Chowdhury pens down why this book is special to her below:

For as long as I can remember, the Kathasaritsagara has been a source of joy and wonder for me. Full of clever women and brave men, its stories have never failed to delight and divert. Its title, which means ‘the ocean of the rivers of story’, immediately brings to mind the image of innumerable rivers of story and their tributary tales flowing into a vast ocean, which at last becomes filled with stories of every kind imaginable. Its title is no exaggeration, for this great work contains within it more than 350 tales told across eighteen books in some twenty thousand stanzas. It is, for its size, the oldest extant collection of stories in the world and is almost twice as long as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey combined.

It was composed around 1070 CE by a Kashmiri Shaivite Brahmin called Somadeva. In a short poem at the end of his work, Somadeva states that he was the court poet of King Anantadeva of Kashmir, and that he composed his Kathasaritsagara for the amusement of Queen Suryavati, wife of King Anantadeva, to distract her mind from its usual occupation of ‘worshipping Shiva and acquiring learning from the great books.’ The Rajatarangini, a chronicle of the kings of Kashmir written by the historian Kalhana in 1149 CE, tells us that the reign of King Anantadeva was one of political unrest, court intrigues, and bloodshed. In 1063, King Anantadeva surrendered his throne to his eldest son Kalasha, but recovered it a few years later. In 1077, the king once again gave up his throne, but this time Kalasha openly attacked his father and took all his wealth. In 1081, the king killed himself in despair, and Suryavati threw herself onto his funeral pyre and perished. It is likely that it was sometime between Anantadeva’s first and second giving up of his throne that Somadeva composed his Kathasaritsagara, possibly around 1070. The Rajatarangini, by independently corroborating the reign of Anantadeva, supports the existence of Somadeva as a real, historical person, and helps us determine with some certainty the time when he composed his great work.

Indian texts were rarely the product of a single individual’s imagination, but were usually put together using stories from various sources and told by different storytellers. Somadeva, too, did not invent the stories that make up the Kathasaritsagara – many of its tales are also contained in much older works, such as the Buddhist Jatakas, the Panchatantra, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and the Puranas and had probably been in existence for centuries, preserved and transmitted orally long before they were ever written down or became a part of Somadeva’s text. Somadeva himself tells us that the Kathasaritsagara is drawn from a much older, and greater, collection of tales called the Brihatkatha, or Great Tale. This greater collection of tales, says Somadeva, is now lost.

Somadeva’s genius lies in the manner in which he has threaded the separate, often unrelated, stories together within the main story, to create a work that engrosses and enchants from the very beginning. Some of the stories take us by surprise, such as that of the clever man who made himself a fortune from a dead mouse. Others, such as the story of the talking bear who refused to betray a friend, make us stop and reflect – on deceit, trickery, and honour. But mainly, the stories entertain and divert. The world of Somadeva’s Kathasaritsagara is rich and vibrant, full of kings, thieves, conmen, merchants, and courtesans. There is war and romance, intrigue and heroism, wit and, sometimes, even wisdom. Like Vishnusharma’s Panchatantra, the Kathasaritsagara is concerned with life and living, but unlike the fables of the Panchatantra, the stories of the Kathasaritsagara teach no moral lessons. Nor are the tales bound by any dominant theme, religion or point of view, but ramble without plan or any purpose except entertainment through their magical world. This makes the work unique in Sanskrit literature.

The Kathasaritsagara has been translated and retold several times since it was written. One of its earliest translations was commissioned by the Mughal emperor Akbar, who came to know of the Kathasaritsagara on a visit to Srinagar after his conquest of Kashmir in 1589 and shortly afterwards ordered it to be translated into Persian. This translation was also lavishly illustrated. Unfortunately, most of the original manuscript was lost and today only nineteen illustrations survive from this translation, scattered in museums and private collections around the world.

The Kathasaritsagar remains unparalleled in its appeal and the undiminished popularity of its tales over the centuries. Its stories are found all over the world – in the more or less contemporary Arabian Nights, in Celtic folklore, and in collections such as the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm. Its influence can be seen in later works such as Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1387 CE) and Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353 CE). In continuing to inspire modern writers such as Salman Rushdie with his novel, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, it remains one of the most influential and best-known non-religious works of Sanskrit literature.

When Puffin’s Sohini Mitra asked me whether I would be interested in retelling, in abridged form, Somadeva’s great work for the Puffin Classics series, I was overjoyed, for I could not imagine a more delightful task. I have based my retelling of the Kathasaritsagara mainly on C.H. Tawney’s English translation published in 1880 by the Asiatic Society of Bengal. For the purposes of this abridged retelling, I have chosen the stories so that they represent, as far as possible, the extent, scope and structure of the whole of the original. Perhaps my favourite story in this selection is that of the carpenter-king, Rajyadhara, and his robot subjects. Though written almost a thousand years ago, it can hold its own against any modern sci-fi tale. Another favourite of mine is the action-packed story of Shringabhuja and Rupashikha, variations of which are found in Norwegian, Sicilian, and Scottish folklore. And there is of course the Vetalapanchaviṃshatik, the twenty-five tales of the Vetala and King Trivikramasena familiar to almost every child in India. Of these riddles, I have included only a few of the most interesting.

By the time Somadeva wrote his Kathasaritsagara, Buddhism had all but disappeared from the Indian subcontinent. In Kashmir, Shaivism was becoming increasingly important, but unlike most of the rest of India, Buddhism still had a significant presence there. Somadeva thus lived and wrote in a climate where multiple religions and philosophies co-existed peacefully. Somadeva dedicates his work to Shiva, but also includes within it, stories about Buddhism and the Buddha, indicating the place that Buddhism occupied in the social and cultural landscape of Kashmir at the time. The story of Ratnadatta and how he learns the meaning of the Buddha’s teachings is a particularly powerful little story, and which I felt deserved a place in this selection.

Given its importance and the universal appeal of its stories, Tales from the Kathasaritsagara is, in my opinion, the perfect introduction to the wonders of Sanskrit literature for young readers.