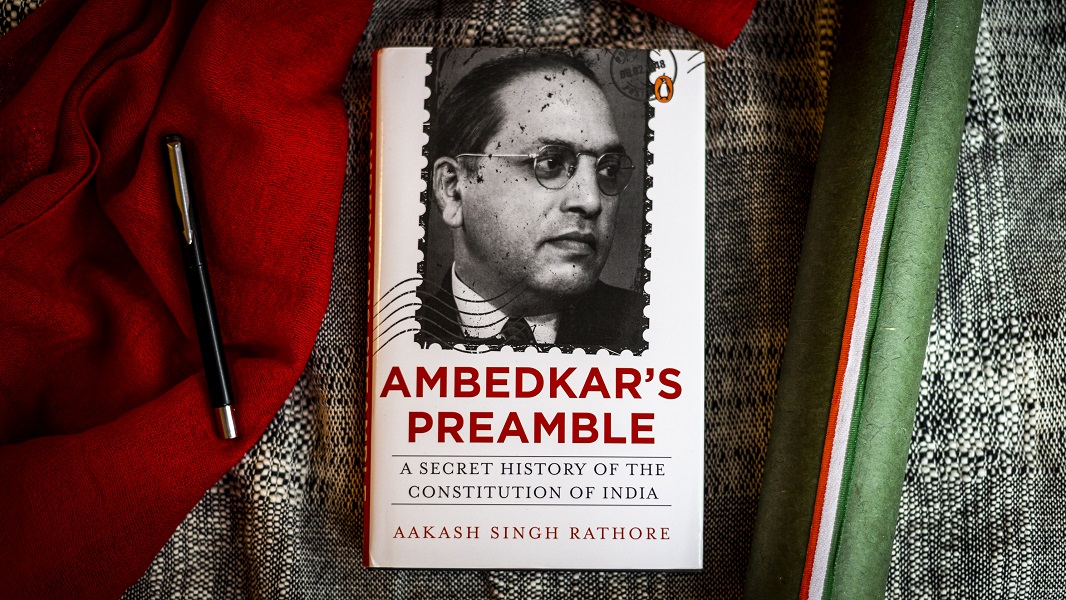

Universally regarded as the chief architect of the Constitution, Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s specific role as chairman of the Drafting Committee and his undeniable authorship of the Preamble became blurred in the haze of conflicting theories about how the Preamble came into being. Formally adopted on 26 January 1950, the Constitution of India has been a subject of interest to many but in Ambedkar’s Preamble, Aakash Singh Rathore establishes the presence of Dr. Ambedkar’s thoughts and beliefs in the intellectual origins of the Preamble and its most central concepts.

Rathore writes ‘Stated succinctly, the Preamble trumpets our collective aspirations as a republic; indeed, it articulates the principles that precondition the possibility for our unity as a nation.’

Read on for a peek into the history of how the Preamble acquired its meaning –

When securing justice implied removal of injustice

Throughout the writings and speeches of Dr. Ambedkar there has been an emphasis on the urgent implementation of policies to instate social justice even more than economic and political justice. When the Preamble was in its nascent stages, many voices raised the need to flesh out the justice clause and debated the inclusion of Nehru’s tripartite formulation of ‘Justice- social, economic and political’, which finally appeared in the Preamble as it was. However, there were no amendments suggested by Dr. Ambedkar to the justice clause even though there was an important underlying difference in his understanding of the concept-

‘In an effort to frame the Objectives Resolution, Dr Ambedkar had put forth his own ‘Proposed Preamble’, which although following Nehru in the tripartite division of social, economic and political, gave substantive meaning to the term ‘justice’ by speaking of the removal of inequalities. That is, where Nehru’s text spoke of securing justice, social, economic and political, Dr Ambedkar’s text interpreted ‘securing justice’ to mean removing social, political and economic inequalities.’

When political liberties nudged social freedoms out of the Preamble

While debates swirled around the subject of freedom and liberty, there was a battle for terms to occupy place of pride in the Preamble. Positive freedoms such as thought, expression, belief, faith, worship which featured on Nehru’s list were pitched against other terms of value on Dr. Ambedkar’s list such as speech, religion and the freedom from want and fear. The final list that made its way into the Preamble established the distinction between fundamental rights and Directive Principles of State Policy.

‘The main components of economic justice, and many of social justice, were relegated to the Directive Principles as they were considered too controversial for inclusion into other binding sections of the Constitution. Similarly, the more robust, labour related freedoms were dropped from their privileged place in the Preamble. Thankfully, however, most of the terms found a place within the body of the Constitution itself, with some eventually being included as fundamental rights.’

When the inequality clause was flipped over

The rather concise equality clause remains unchanged from the way it was drafted and added to the Preamble. However, the clause ‘EQUALITY of status and of opportunity…’ is the briefer version of what was proposed in Nehru’s Objectives Resolution. Another turn in the history of this clause was that Dr. Ambedkar had, in fact, proposed an ‘inequality’ clause!

‘It may come as some surprise, however, that in Dr Ambedkar’s ‘Proposed Preamble’ from States and Minorities (March 1947), there was not really an ‘equality’ clause at all, at least not a positive one. Instead, there was an ‘inequality’ clause:

(iii) To remove social, political and economic inequality by providing better opportunities to the submerged classes.’

When the term ‘fraternity’ brought Gandhian ideas into the constitutional draft

One of the main pillars on which our Preamble stands upright is the ‘fraternity clause’. However, this clause did not feature in any of the preliminary drafts to the Preamble and Constitution of India. Added by Dr. Ambedkar, this clause went on to become the only universally applauded clause in the Constituent Assembly for its inclusion of an aspect of morality amongst mostly legal and constitutional principles.

‘On 6 February 1948, the clause first read: Fraternity, assuring the dignity of every individual without distinction of caste or creed.

This is purely the Ambedkarian formulation of fraternity, quite in line with the history of Dr Ambedkar’s articulation of the concept in his own writings, dating back to the 1930s… It drew upon fraternity as a resource for upholding individual dignity, which remains perpetually degraded due to the distinctions of caste.’

The terms ‘JUSTICE, LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY, Dignity and Nation’ contain layers of meaning and form the basis of the progressive and liberal values espoused by the Preamble.

‘It is these six words that allow us to hack into the DNA of Dr Ambedkar’s preamble, gaining access to many of its secrets.’ establishes Rathore as he takes us back into the intense debates and discussions within the Constituent Assembly and the Drafting Committee that decided the final inclusions in the Preamble.

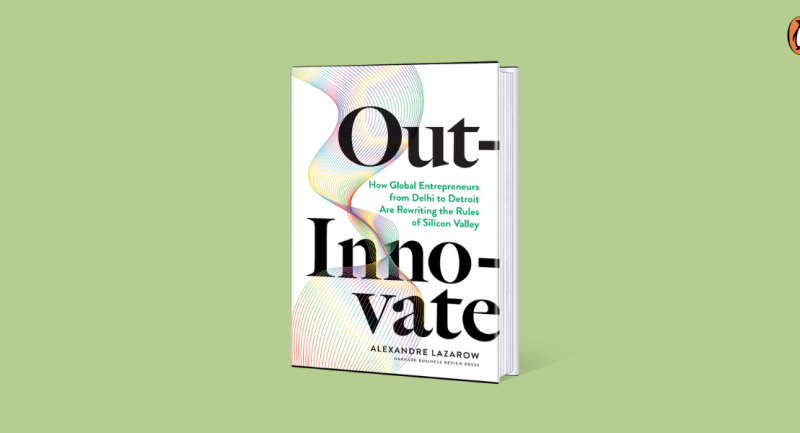

To know more about the journey of the soul of India’s Constitution, read Ambedkar’s Preamble!