When the Kingdom of Aum falls under the spell of corrupt forces, all its past glory turns to dust and the land, once lush and fertile, becomes a barren wasteland. It falls upon Saahas, the courageous young General and heir to the throne, to fight the darkness that had shrouded his beloved Aum. But victory eludes Saahas as the play of destiny takes him on a journey both arduous and treacherous. General Saahas becomes a hunted man and Aum plunges into chaos, submitting meekly to the tyranny of the self-appointed Raja Shunen and the wily Queen Manmaani.

What was this web that Saahas had become entangled in?

Submerged under wave upon wave of dilemmas, Saahas is bewildered by the power of the Saade Saati–the dreaded seven and a half years- yet is determined to find his way towards his destiny.

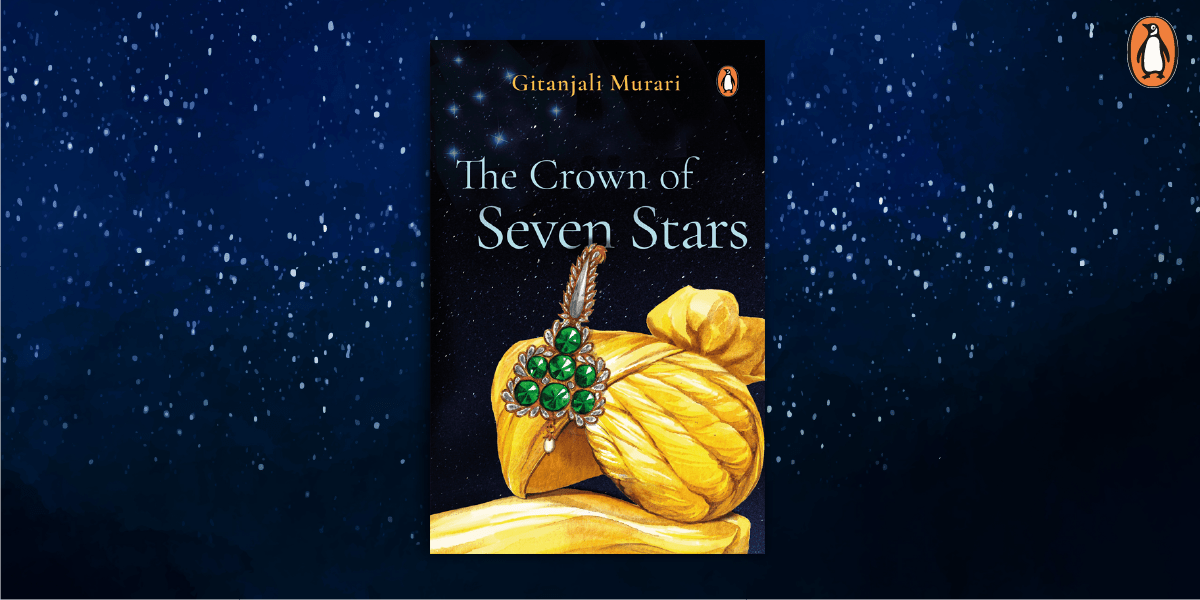

Gitanjali Murari’s The Crown of the Seven Stars begins with a letter from Destiny which hints at a revelation- ‘And I promise you an enthralling story of one man who dared to fight me, catching me quite unawares, so revealing the truth about these accursed seven and a half years.’

Read on to find out what the period of Saade Saati brings –

The fear of failure

Saade Saati, the dreaded seven and a half years that befall each person at least once in their lifetime, brings with it crushing failure-

‘You fear it, for it results in nothing but failure; failure that eats you from the inside, corroding you, until you wish you were dead. And when you emerge on the other side of it, you weep, not with relief, but because you are quite broken.’

*

There is light at the end of the tunnel

Saade Saati may make the sufferer feel helpless and fearful but it is a finite period which does come to an end and the wheels of fortune turn again. The astrologer Arigotra leaves Saahas with hope for the future but also a reminder of the futility of his battle against Saade Saati –

‘Eight months of it have already passed. Less than seven years remain. Go away, my lord, and only return when the time turns auspicious.’ The dying man’s words smote Saahas with the finality of a hammer. They laid bare his helplessness, making him acutely conscious that the hopes he had cherished on his journey back to Aham were laughably puerile.’

*

The right attitude is key to getting past this play of destiny

Acceptance and patience may help sufferers find value even in a bleak situation. The old priest of Yadoba offers some perspective to Saahas who is consumed with the idea that the period of Saade Saati is ‘fruitless’-

‘But if the soldier were to take a deep breath, calm down and contain his vital energy instead of wasting it by running from pillar to post, he will realize that the Saade Saati, far from being a curse, is a boon. It is the gods telling us to stop and reflect, to know ourselves, learn a new trade perhaps, spend time with the family, study the scriptures. Anything—read, play, evolve.’

*

The learning is in the experience, not in despair

Whatever destiny may have in store for you, the period of Saade Saati can be a learning experience. As Destiny reveals the motive behind this game, a ray of sunshine pierces through clouds of bewilderment-

‘You see, I had always planned for Saahas to be king. The Saade Saati, the trials, the tribulations, I had gone to so much trouble to create obstacles for him. Just so he would become the king Aum deserved.’

With destiny rolling her dice at every turn, will Saahas emerge wise and fearless from the maze of the Saade Saati? Would the throne find its rightful heir?

Read Gitanjali Murari’s The Crown of the Seven Stars to find out!