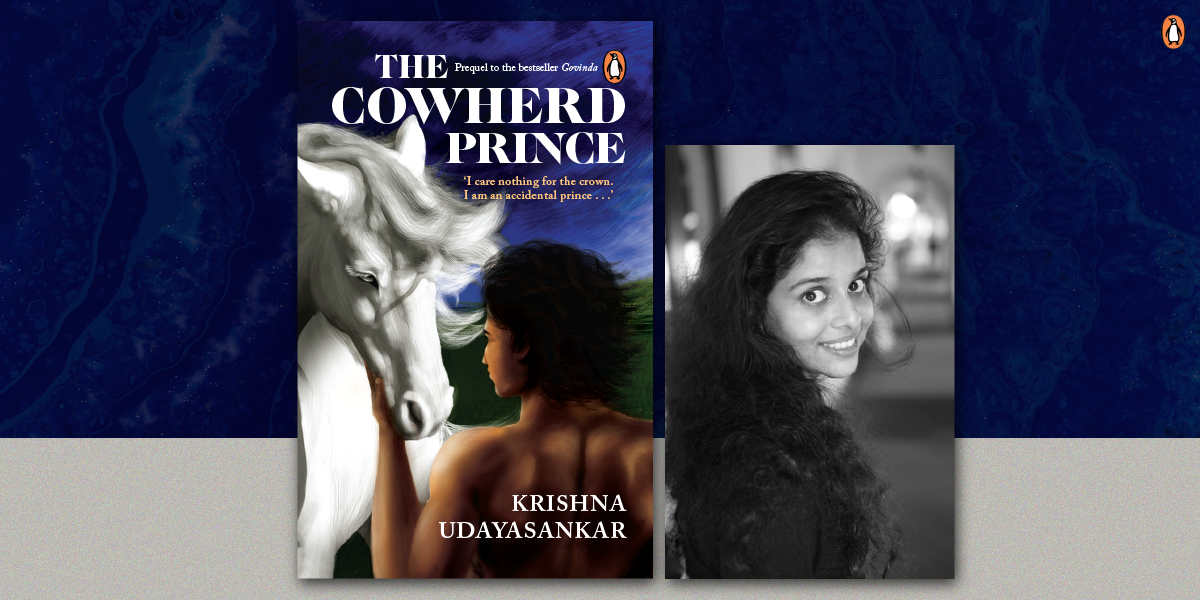

If you just cannot get enough of The Cowherd Prince, you are not alone. Krishna Udayasankar’s prequel to the bestselling novel Govinda is a thrilling insight into the world of Govinda before he became the master strategist of The Mahabharata. We had a chat with the author and it was an absolute delight!

~

We hear you’re a science fiction buff. Who are your favourite writers in the genre?

KU: I was a huge fan of Isaac Asimov as a child and teenager. I mean, I still am, but it’s difficult to say that now without asking myself questions about separating the art from the artist – after the allegations of harassment against Asimov. But I can’t stop liking what I’ve liked all these years, I can’t change the fact that I love the books and have been influenced greatly by them. So yes…

You characterise your protagonist Govinda very carefully. You have also said that consent is one of the most important things to learn from Govinda. What would you say is the importance of looking at mythological characters from a more contemporary lens?

KU: Fiction is a device by which we look at the world around us, all the more so for genres that deal with alternate worlds, like myth and history or fantasy. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that good fiction is always a commentary on the way the world is. When it comes to mythology, I believe that becomes even more important because it is a two-way thing – the way we understand our past, the way we believe things happened, are fundamental parts of how society functions in the present. And if we want to question our present or examine it, then we also need to examine our understanding of myth or the pre-historic past – all the more so because for a large part of our society, myth is the bedrock of defining good and bad, right and wrong.

We also hear that you hate spinach. If abandoned on a deserted island with only spinach to eat, which three books would you take with you?

KU: Haha! Since I would not eat a book or tear it up even if I were starving, I assume the question is which books can make the spinach go down easier? Traditionally, it would be Amar Chitra Kathas – since those were the spinach-y books of my childhood. But now my list would be: My entire Calvin and Hobbes collection, Kalki’s Ponniyin Selvan and Asimov’s Foundation series. And maybe I’d try to sneak in Lord of the Rings too? And The Jungle Book. And … wait a minute, three books? I can survive on spinach but I can’t survive on only three books.

What are you reading now? What book are you excited to read next?

KU: I am re-reading Martha Well’s Murderbot novellas in anticipation of reading her latest – a full Murderbot novel next.

What is your favourite thing about being a writer?

KU: Hanging out with some amazing (imaginary) people. Living in other worlds. Travelling to places I have never been, vicariously doing things I can’t dream of doing otherwise in this lifetime (whether it’s flying a fighter jet or whipping up a six-course meal!) And of course, one of the best parts of being a writer is getting to share these experiences with readers – who often become friends.

How do you battle writer’s block?

KU: I don’t battle it, not anymore! All I do is show up every day, even if that means I’m doing nothing other than stare at a blank page. But that is when I am writing. I often go for months without writing, particularly between books. I’ve learnt that imagining new worlds, new stories is one of the best parts of writing (other than playing with words). I tell myself now, that its ok to do that, and the story will come to me when it has to.

What is your writing process like? Are you a planner, or do you wing it, or is there a third customized method that works for you?

KU: I’m a mix of planned, chaotic and downright clueless. I think I try different methods at different points on time in a book – usually winging it when I begin, then stepping back to plan a little bit, then just being instinctive about it again. I also work on multiple books, sometimes, so I could be following different processes at once. Like I said, clueless and chaotic!

~

Krishna Udayasankar’s The Cowherd Prince is captivating and will keep you reading well into the early hours of the morning.