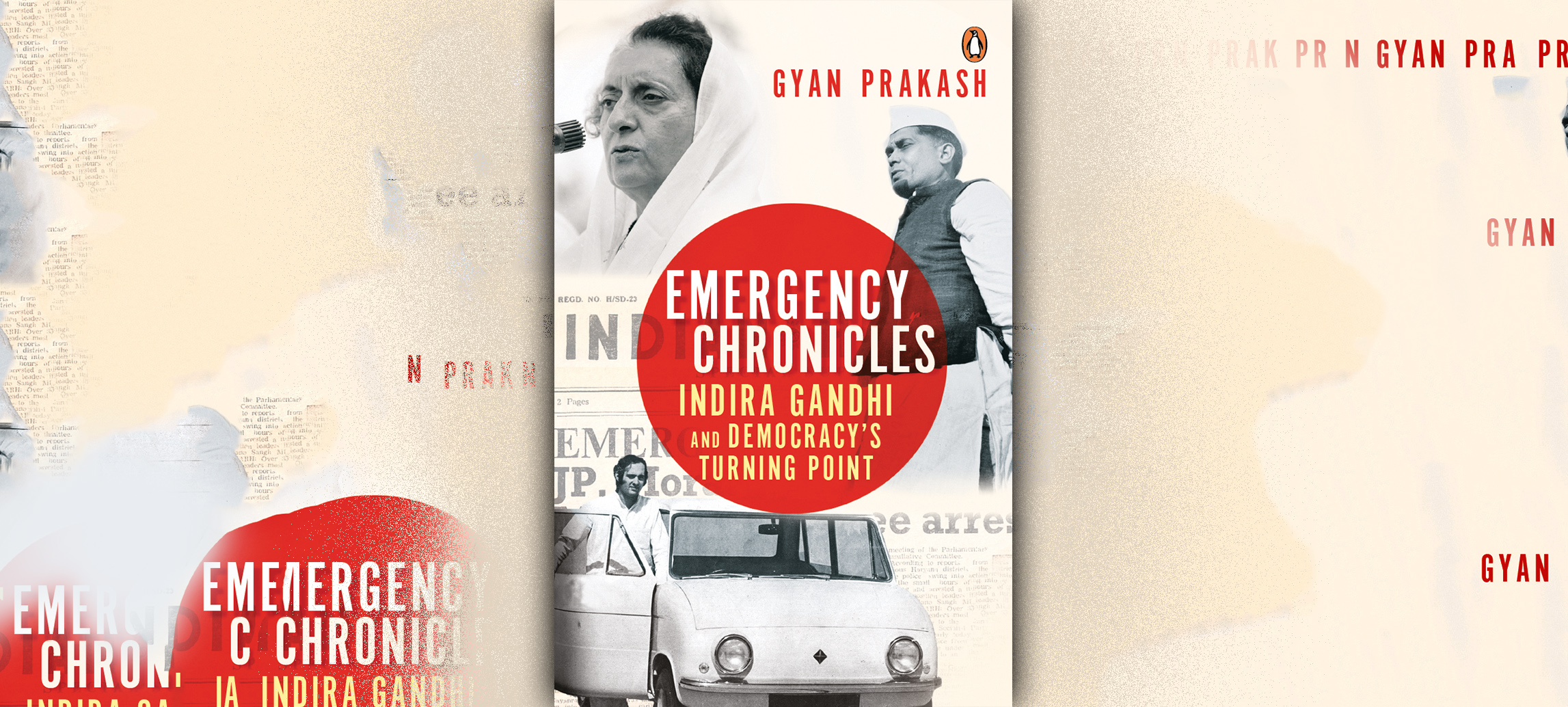

As the world once again confronts an eruption of authoritarianism, Gyan Prakash’s Emergency Chronicles takes us back to the moment of India’s independence to offer a comprehensive historical account of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency of 1975-77. Stripping away the myth that this was a sudden event brought on solely by the Prime Minister’s desire to cling to power, it argues that the Emergency was as much Indira’s doing as it was the product of Indian democracy’s troubled relationship with popular politics, and a turning point in its history.

Here is an excerpt from the prologue of his book.

On the recommendation of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the president of India declared a state of Emergency just before midnight on June 25, 1975, claiming the existence of a threat to the internal security of the nation. The declaration suspended the constitutional rights of free speech and assembly, imposed censorship on the press, limited the power of the judiciary to review the executive’s actions, and ordered the arrest of opposition leaders. Before dawn broke, the police swooped down on the government’s opponents. Among those arrested was seventy- two- year- old Gandhian socialist Jayaprakash Narayan. Popularly known as JP, Narayan was widely respected as a freedom fighter against British rule and had once been a close associate of Indira’s father, Jawaharlal Nehru. In 1973, JP had come out of political retirement to lead a student and youth upsurge against Indira’s rule. Although most opposition political parties supported and joined his effort to unseat Indira, JP denied that his goal was narrowly political. He claimed his fight was for a fundamental social and political transformation to extend democracy, for what he called Total Revolution. JP addressed mass rallies of hundreds of thousands in the months preceding the imposition of the Emergency, charging Indira’s Congress party government with corruption and corroding democratic governance.

was reminded of the JP- led popular upsurge in August 2011, when I saw a crowd of tens of thousands brave the searing Delhi heat to gather in the Ramlila Maidan, a large ground customarily used for holding religious events and political rallies. Young and old, but mostly young, they came from all over the city and beyond in response to a call by the anti- corruption movement led by another Gandhian activist, seventy- four- yearold Anna Hazare. The atmosphere in the Maidan was festive, the air charged with raw energy and expectations of change. The trigger for the anti- corruption movement was the scandal that broke in 2010 alleging that ministers and officials of the ruling Congress party government had granted favors to telecom business interests, costing the exchequer billions of dollars. Widely reported in newspapers, on television, and on social media, the alleged scam rocked the country. It struck a chord with the experiences of ordinary Indians whose interactions with officialdom forced them to pay bribes for such routine matters as obtaining a driving license, receiving entitled welfare subsidies, or even just getting birth and death certificates. Venality at the top appeared to encapsulate the rot in the system that forced the common people to practice dishonesty and deceit in their daily lives. Into this prevailing atmosphere of disgust with the political system stepped Anna Hazare. Previously known for his activism in local struggles, he shot into the national limelight as an anti- corruption apostle when he went on a hunger strike in April 2011 to demand the appointment of a constitutionally protected ombudsman who would prosecute corrupt politicians. His fast sparked nationwide protests, giving birth to the anti- corruption movement. An unnerved Congress government capitulated, but the weak legislation it proposed did not satisfy Hazare, who announced another fast in protest. The hundreds of thousands who gathered in August 2011 had come to show their support for his call to cleanse democracy. When the diminutive Hazare appeared on the raised platform, a roar of approval rent the air.

Meanwhile, as the newspapers and television channels reported, the ruling Congress leaders fretted nervously in their offices and bungalows, uncertain how to respond to something without a clear political script. In a reprise of 1975, it was again a Gandhian who was shaking the government to its core with his powerful anti- corruption movement, arguing that the formal protocols of liberal democracy had to bend to the people’s will. And like his Gandhian predecessor Jayaprakash Narayan, Hazare enjoyed great moral prestige as a social worker without political ambitions. Similar to the 2010 Arab Spring and the Occupy movements, there was something organic about the 2011 popular upsurge in India. The enthusiastic participants demanding to be heard were mostly young and without affiliation to organized political parties. The Tahrir Square uprising ended the Mubarak regime; the Occupy movement introduced the language of the 99 versus 1 percent in political discourse; and the Congress government in India never recovered from the stigma of corruption foisted on it by the Anna Hazare movement, leading to its defeat in the 2014 parliamentary elections.

Since then, the populist politics of ressentiment has convulsed the world. In India, the Narendra Modi– led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) devised a clever electoral campaign that used the “development” slogan while stoking Hindu majoritarian resentments against minorities to ride to power in 2014.1 We have witnessed anti- immigrant and Islamophobic sentiments whipped up in the successful Brexit campaign and Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Across Europe, a roiling backlash against refugees has reshaped the political landscape. The role of conventional political parties as gatekeepers of liberal democracy in Germany, France, Italy, and several other countries is in crisis under the pressure of majoritarian sentiments. Strongmen like Victor Orbán in Hungary, Recep Erdoğan in Turkey, and Rodrigo Dutarte in the Philippines have mobilized populist anger as a strategy of rule. They incite pent- up anger and a sense of humiliation to fuel rightwing nationalist insurgencies against groups depicted as enemies of “the people” to shore up their authoritarian power and suppress dissent.

In Emergency Chronicles, Gyan Prakash delves into the chronicles of the preceding years to reveal how the fine balance between state power and civil rights was upset by the unfulfilled promise of democratic transformation.