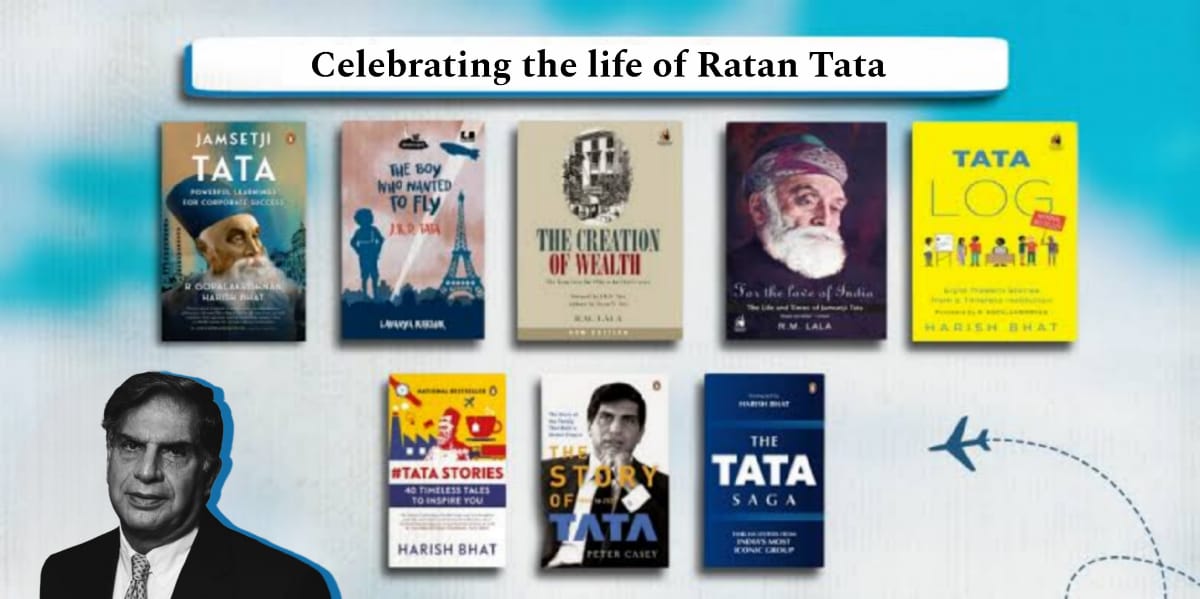

There’s nothing like the joy of immersing ourselves in a good story especially when we can listen to it on-the-go or in the comfort of our homes. This carefully curated selection of audiobooks offers a rich selection of tales that transport us to new worlds, deepen our understanding, and fill our days with inspiration and excitement. Plug in, sit back, and let these stories keep you company as we remember the Tatas and their contribution to the nation.

Tatalog presents eight riveting and hitherto untold stories about the strategic and operational challenges that Tata companies have faced over the past two decades and the forward thinking and determination that have raised the brand to new heights. From Tata Indica, the first completely Indian car; to the jewelry brand Tanishq; and Tata Finance, which survived several tribulations, Tatalog, written by a Tata insider, reveals the DNA of every Tata enterprise – a combination of being pioneering, purposive, principled, and “not perfect”.

“His vision made giants out of men and organizations.” A pioneer, an adventurer, a great industrialist and a caring, courageous human being…the story of J.R.D. Tata is fascinating. His biography is the tale of determination, integrity and prodigious intelligence.

One day, the headlines boldly declared that the chairman of the board of Tata Sons, Cyrus Mistry, had been fired. What went wrong? In this exclusive and authorized book, insiders of the Tata businesses open up to Peter Casey for the first time to tell the story. From its humble beginnings as a mercantile company to its growth as a successful yet philanthropic organization to its recent brush with Mistry, this is a book that every business-minded individual must hear.

Founded in 1868 by Jamshetji Tata, the Tata Group symbolizes the great Indian story of hope, growth and phenomenal success.The group played the role of a nation builder in post- independent India. In The Learning Factory, Arun Maira narrates people-centric episodes that bring alive the values of the Tata Group, standards that combine the high-velocity practices as well as the old-fashioned principles that make the Tata Group the giant it is today.

With over 100 companies offering products and services across 150 countries, 700,000 employees contributing a revenue of US $100 billion, the Tata Group is India’s largest and most globalized business conglomerate. A deepdive into the Tata universe, The Tata Group brings forth hitherto lesser-known facts and insights. It also brings you face-to-face with the most intriguing business decisions and their makers. How did Tata Motors turn around Jaguar Land Rover when Ford failed to do so? Why wasn’t TCS listed during the IT boom? Why wasn’t Tata Steel’s Corus acquisition successful?

The Tatas have a legacy of nation-building over 150 years. Dancing across this long arc of time are thousands of beautiful, astonishing stories, many of which can inspire and provoke us, even move us to meaningful action in our own lives.#TataStories is a collection of little-known tales of individuals, events, and places from the Tata Group that have shaped the India we live in today.

Jamsetji Tata pioneered modern Indian industry. He has been a key catalyst in the economic growth and development of the country. In this carefully researched account, R. Gopalakrishnan and Harish Bhat provide insights into the entrepreneurial principles of Jamsetji that helped created such a successful and enduring enterprise. Interwoven with engaging real-life stories and interesting anecdotes that went into the making of India’s popular brands such as Tata Tea, Tata Motors, Titan and Tanishq, this unique account brings alive the vision of Jamsetji Tata and what we can learn from it.