Both of us grew up in the same ghetto and studied in the same school. Both of us struggled against hunger. Yet we parted ways and made tracks in diametrically opposite directions. Iqbal says that it is destiny. I have already stated earlier that I chose my own path, my own battlefield, my own destiny.

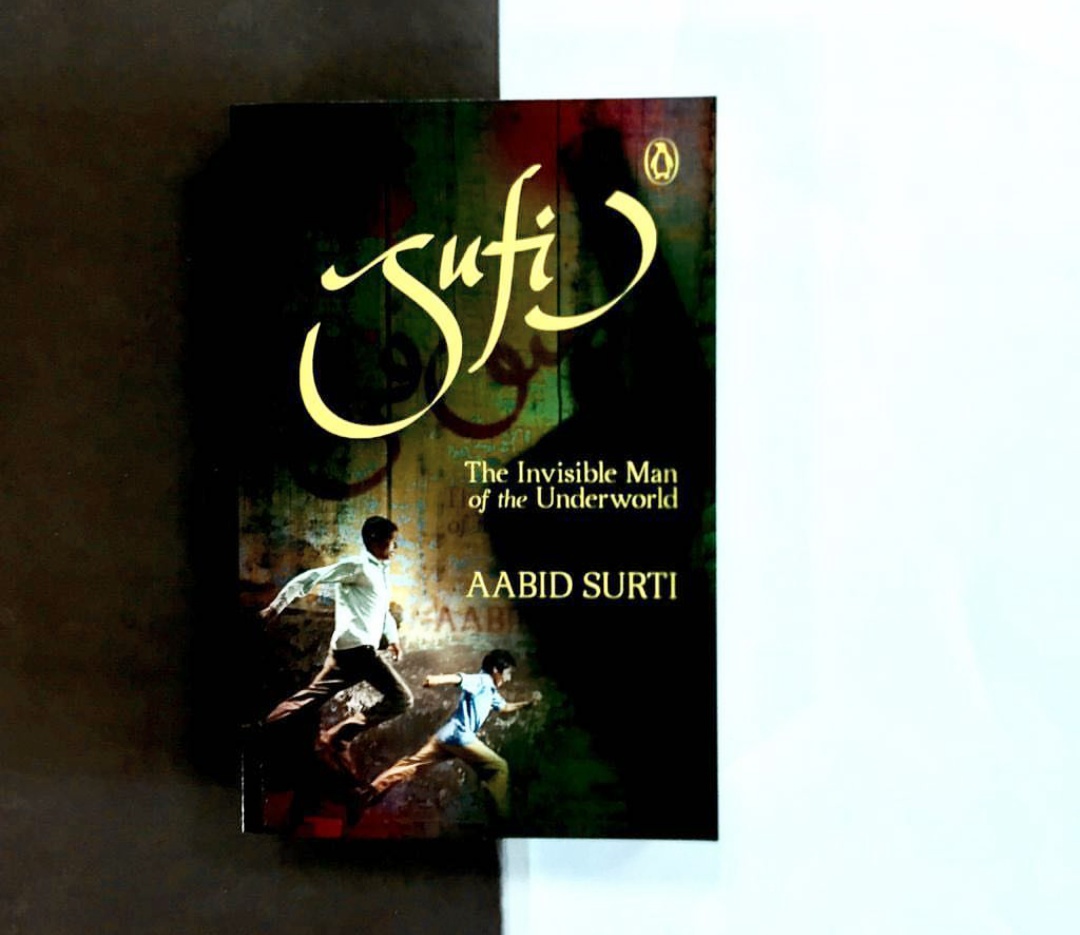

Sufi is the story of two boys who grew up playing in the alleys of Mumbai’s infamous Dongri locality.

One of them, Iqbal Rupani, aided and abetted by a corrupt policeman, is drawn towards criminal activities in his teens. As he becomes powerful and influential as a racketeer and smuggler, he creates a puritan code of conduct for himself: no drinking, no smoking and no murders. The other boy, Aabid Surti, grows up to become a famous author.

‘Sufi’ is a unique autobiography, a ‘jugalbandi’, rather than a ‘one person’s life sketch’-detailing the extraordinary parallel trajectories of two extraordinary men—Iqbal, a juggernaut during the golden period of gold smuggling in India, and a man who paradoxically comes across as a Sufi ‘an enlightened soul’, in his disciplined personality and his philosophies— and the other, Aabid who is a creative powerhouse, an author, comic book creator and artist.

Read on to trace some of the most incredible similarities in their lives.

Their education and their early ambitions were starkly similar.

Both of them completed their education from Dongri’s renowned Habib High School. Its distinguished principal Padma Shri awardee Sheikh Hasan, considered both among his favourite students. Both boys had a sincere desire to study hard and succeed in life.

Their early aversions to marriage came to naught, as they end up marrying women from the same close-knit clan, and who share the same first name.

As they grew into adults, neither was interested in marriage. They knew that young men struggling to make their mark in the world were not able to shoulder the responsibilities of married life. However, both were compelled by the twists of destiny into wedlock. Not only did their wives belong to the same family clam they even had the same first names.

Their places of residence from birth to the present remain in close proximity.

Today both of us live in Bandra, an affluent cosmopolitan suburb in Bombay. Back then we lived near Bhendi bazaar in the squalid Muslim ghetto known as Dongri.

Their early struggles were without the backing of their fathers who both fought their personal demons, but in different ways.

Before Sufi’s birth even his father Husain Ali had fallen prey to the affliction of alcohol…Hussain Ali’s alchoholism was sparking its final blaze. The more he strengthened his resolve to quit, the more he ended up drinking. Defeated by life, my father, Ghulam Hussain too made a last-ditch attempt. While Sufi’s father had turned to smuggling because of his wife’s disease, my father had turned to propitiating spirits as the last resort to end his suffering because of his poverty and hunger.

Their earliest forays into earning a semblance of a living were the same.

I started selling chikki (sweets made from nuts and jaggert), peppermint and sweet-and-sour candies. I used to sit with my cookie-candy basket on the pavement of Dongri’s main road. Iqbal would emerge from his house in Munda Galli, come to Pala Galli and sit near Khoja Masjid. His basket would contain berries, amla and other wild fruit besides candies. Sufi is the story of two boys who grew up in Dongri, Mumbai.

In a mysterious co-incidence, both their fathers announced their deaths beforehand.

Like Hussain Ali, my father. Ghulam Hussain, too announced his end beforehand. Not with an ambiguous statement like, ‘My time is up’, but with a calm yet explicit warning: ‘No one should leave the house tomorrow else you won’t see my face ever again.

The mentors found them at a vulnerable time but were of a very different nature —Dr RJ Chinwala, the famous art patron, and the corrupt police officer, Inspector Bharucha

I became a member of Dr Chinwala’s extended family. Dhala was to become my guru in the field of art , while Mushtaq Ali taught me the art and craft of storytelling. Dr Chinwala was to play an important role in shaping my life. Inspector Bharucha meanwhile would chart out a new course for Iqbal, but there was a difference between the two courses. One was positive while the other was negative. One led to creativity, beauty and progress, while the other led to destruction, deception and ultimately, ruin.

They experienced their first romantic awakenings in the same year.

Iqbal brutally uprooted the sapling of first love before it could bloom. The same year love sprouted its tiny leaves for the first time in my life. I had time to nurture this fragrant plant. There was peace in my life.

The ambitions of their first loves remained unfulfilled but in very different ways and for very different reasons. Iqbal made a conscious decision to leave the woman he loved, while Aabid’s romance with Suraiyya ended abruptly when she was forcibly deported by her family.

Where the heart rules, the pain is always intense. The seed of Iqbal’s and Kiran’s love may have sprouted but it progressed only after a careful consideration of all aspects of life, and its end too was to come after much mental deliberation. Our love had been blind because our wild hearts ruled over our minds; their love could see all too clearly because their minds examined everything, kept everything in check. Both couples dived into the ocean of love, but one took the plunge with eyes closed while the other kept everything in check.

After years of hard work both ended up failing their examinations. This put a premature end to their promising academic careers and launched them even more firmly on their chosen paths.

Upon its publication, the novel Tutela Farishta (Fallen Angels) became the talk of the town. But before that I had failed in my final-year art examination. Like me, Iqbal too had always been a first-class student. But his tragedy unfolded differently. In those days conjunctivitis had seized Bombay. Just two days before his final examinations. He fell victim to this epidemic. He did not lose hope. To fulfill his father’s dream of him becoming a doctor, he put eye drops and sat for the examination, but failed to answer any of the questions. He couldn’t read a single line.

Sufi is the story of two boys who grew up in Dongri, Mumbai whose paths diverged drastically.